The Importance Of Seeing Things From The Customer’s Point Of View

August 07, 2024

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

If you run a business, are you sure that every detail is being handled? When the little things aren’t being taken care of, it can be an indication that the big things aren’t going well. In this episode, Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff share the enormously important things companies have to do now to make sure customers keep coming back.

Show Notes:

In businesses, one of the first things to go is customer service.

The only reason to shop in person rather than online is because it becomes a social event in a certain way.

The purpose of automation can be to free someone up so they can have more time with customers.

When a company starts cutting costs, especially by firing people, it shows you that they’re packaging the company for sale.

The cost of personal service is going up.

People interacting with people has a hundred times more dimensions than people interacting with mechanical replacements for people.

Some people delude themselves into thinking that because AI can form an answer, it’s somehow sentient and like a person but even more efficient.

These days, luxury means an actual person paying attention to you.

It’s harder to get people’s attention now than it was 30 years ago.

Having a great reputation is much more important than having great marketing.

Resources:

Who Not How by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy

The Gap And The Gain by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy

10x Is Easier Than 2x by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy

Within The Context of No Context by George W.S. Trow

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything And Everything with my partner Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: We were having a talk just before we started recording, Jeff, about public places that you notice whether they're well kept up or not, whether they're maintained. And in particular, I was zeroing in on restaurants, brand new restaurants. And you go there fairly soon after they have opened the doors, but you're in the restroom and you notice there's a mark on the wall like somebody- It might have been intentional, or something happened. And you go back again a month later, and the mark is still there. And you know that that restaurant is not doing well because they're not taking care of the little things. So it sort of indicates that the big things aren't going well. What's your take on that?

Jeffrey Madoff: It's interesting you say it. There was a change that you and I were talking about that happened in New York, for instance, and this was where vandalism and the phrase, you know, "breaking the warehouse windows" came into play, where these were, for the most part, abandoned buildings, but things that happened to those buildings, like windows being broken by people throwing rocks through them, became okay in the sense that there was no consequence to doing it. And you could tell, obviously, that was in decline because it was abandoned. Well, then you jump to a restaurant or you jump to a store and you start seeing telltale indications, like what you're saying, minor things that aren't taken care of quickly. In the restaurant, it can be something in the bathroom, or if you belong to a health club, it can be that the machines aren't getting repaired quickly and they're out of order for days, or inventory depleted in stores. You know, there's just these telltale signs that smell like decline.

So I think that there is a lot of that, and I guess the question is, why does that happen? And we've touched on this before, and this might be an interesting place to go too. In businesses, one of the first things to go is customer service. And the only reason to shop in person rather than online, other than finding out your size or something, is because it becomes a social event along with it in a certain way. So how do you see that translated into the different kinds of businesses? Because you cross over into so many kinds of businesses through your members at Strategic Coach. How do you see that manifest?

Dan Sullivan: Well, we have a rule in Strategic Coach that if we're using technology as part of our interaction with customers, the customer should never see or experience the technology. They should always experience the person. I feel that very, very strongly about artificial intelligence, which is, you know, it's a bit of a rage right now. And I said, you never have something mechanical dealing with customers. You always have a person. The purpose of the automation is to free our person up so that they can have more customer time. So anytime I see a drop off in customer service, then I know things are not going well backstage.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that's a great point in terms of how you're using it. As opposed to, I don't believe that you can cut your expense way into profits. And companies do that all the time when they're looking to be acquired or pump up stock value and so on is, I'll go through a massive…

Dan Sullivan: You can delay bankruptcy by cost cutting, but you can't... Hopefully you can sell the company before the other party understands. But I think that it kind of shows you that they're packaging it for sale when they start cutting costs, especially human costs when you start firing people.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. In your case, The goal of any automation is to free up more people time.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you have more contact, person to person. My feeling is that we're in an interesting period, and COVID, I think, was an interesting test period, that the cost of personal service is definitely going up. You know, and I think people are not realizing that people like people. People interact with people a hundred times more dimensions than interacting with mechanical replacement for a person.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you're right, except for those that delude themselves into somehow thinking that because something can form an answer, and I'm talking about AI now, that they think it's somehow sentient and that it's like a person but even more efficient. And one of the big selling points, I think, for certain kinds of AI in business, there are things that make a lot of sense in terms of using it. You know, faster retrieval of information, customer histories, all these kinds of patterns that you can find out and so on. But in terms of the day-to-day operating, you don't get the benefits of human contact, I think, are greatly missed. And I think that for instance, in the fashion world and in anything that's expensive, luxury, let's call them, the luxury markets. One of the reasons that they were doing well in a challenged economy was, of course, there was a lot of money concentrated into smaller places. And that was one thing. But I also think that these days, luxury means an actual person paying attention to you.

How do you define that?

Dan Sullivan: I remember, it was about maybe a year ago, you were talking about being at a meeting with marketing experts from the fashion industry, and you were telling them that their greater and greater reliance on mechanical communication, mechanical marketing was just hitting a wall. Do you remember that discussion? You had just had the meeting several days before we had our podcast, and you were talking about, you know, that they were putting enormous emphasis on getting eyeballs to look at their mechanical ads, but it wasn't translating into sales. Certainly wasn't translating into profitable sales.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and I think that one of the reasons is that the more obstacles you put in the way to that journey to the cash register, so to speak. And the more impersonal you make it, the less, how can I say this? One of the biggest things in fashion, and it's, I think, true in automotives, it's true in a lot of areas, you want to build customer loyalty. So if they buy a BMW, they always want to buy BMWs. You know, if you go to take kids to Disney, you always take kids to Disney because the experience is so wonderful. And I think that in these situations where there are so many obstacles that are set up to the final transaction, that business suffers. And one of the main differentiators, and I think this is a conversation you may be referring to, one of the main differentiators is, when you actually are interacting with a human. And the interesting thing about that is the obstacles in that, like when you have to go through five different voicemail prompts just to hopefully get to somebody, but you usually end up on hold for 20 minutes, were actually built to discourage that interaction. They were truly built to discourage that because it cost them money. It cost the companies money, so they tried to eliminate that. So meanwhile, you go into a big store, you're ready to drop $800 on a jacket or something, and you can't even find anybody to pay.

Dan Sullivan: Or you're standing in line for 15 minutes to get to a cashier.

Jeffrey Madoff: Exactly. Exactly.

Dan Sullivan: They're encouraging you all along to pay with an automatic machine.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. Well, yeah, I've noticed just recently to this point, and this is on consumer goods we all interact with, not luxury, but I forget which grocery store chain it was. They were removing all of the automated checkouts.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, I had that example in the sort of it's the most fashionable part of Toronto. It's called Yorkville. All the high-end brands are in this area. It's about five blocks by three blocks, maybe 10 blocks by three blocks. You know, luxury hotels, upscale restaurants, but then the retail stores. But there's sort of a legendary produce store that's been two or three generations in Toronto. I went in during COVID, and they had replaced three live cashiers with five machines. And it's the last time I went. I used to go weekly, and now I haven't gone there. And I said, you're already charging me 20% more. I mean, it's not a cheap store, but nice produce and nicely packaged and everything. I like the experience. As you say, it's a nice social experience. But not with the machines, it's not a nice social experience.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. And I'll bet you that there is a significant number of people on those automated checkouts that still need the help of somebody because something didn't- Can I take the card out now? Wait, where do I, you know, whatever it is. Like, there's a store, they're all over the place, but Trader Joe's. They're always packed on the Upper West Side of New York. They're always busy. And they have people dedicated to the traffic flow that direct the people who are in line to go to this, to go to that. Now, they still have the light, you know, on the number, what's available. But they have people who are monitoring the people who are very pleasant. And all the store staff is very pleasant and well trained at Trader Joe's. And you interact. There is no fully automated. You're interacting with a cashier. And it's striking that, if you talk to somebody stocking the shelves and you ask them something, they actually have an answer. And they train their employees to enhance the experience for the customers. So they have very good prices, good quality food, and they train the people because, you know, what's more basic than sort of buying food, right?

And usually these grocery stores have become warehouses that you wheel your cart up to, and there's, you know, the self-checkout, which they look at as this big boon in cost savings. That, and there's another thing, and then I will be quiet for a moment, but it surfaces a lot of thoughts to me. I hate going to a restaurant that wants me to scan so I can look at the menu on my phone.

Dan Sullivan: Me too.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's a total pain in the ass, and I started doing very informal, unscientific market research. And these are, by the way, restaurants of all costs. And it's really interesting because I would say to people—these are nice restaurants—"You know, I know I'm older, but do your clients like the barcode scan to see the menu on their phone?" Without exception, everyone said, "Oh God, they hate it."

Dan Sullivan: Which makes you wonder.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Yeah. Maybe it seemed like a good idea at the time, but it's not.

Dan Sullivan: I expect it at airport, you know, I mean, we go through a lot of airports, and it's fast food, and you really kind of expect it. So I don't have any problem with it there, but even there, I'm not doing it. Babs is doing it. I always keep smart humans between me and the technology. Rule number one, always keep a smart human between you and the latest technology. But the big thing about it is that they're not seeing things from the customer experience. I mean, it's just a human thing. The best way to be friends with someone is to sort of understand how they look at the world and kind of match up your experiences with their experiences. I think it works in politics. I think it works in romance. I think it really works. And I think the reason is because the whole operation from start to finish has gotten commoditized. It's about the amount of money we're making, not about who we're serving in the public.

Jeffrey Madoff: Absolutely. Well put. That's right. You know, when I first started coming to New York in 1967, '68, then moved here in '74. And there was, you know, either subways and buses. There was no Uber or no Lyft or any of that. But I would get into a cab, and as I got in, I would read the person's name and I would go, "Hey, Mohammed." And they'd look at me in, like, total surprise. It was also interesting, Dan, because it was before cell phones. And I had interesting conversations. "And when did you come to the United States?"

Dan Sullivan: Me too.

Jeffrey Madoff: "What drew you to here?" And all of that, gone for the most part. That's gone. Which I would never allow. If I ruled the world, if I was a head of the, you know, the cab union, whatever it's called, I would say, you cannot talk on the phone while driving.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you can't take calls.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: I have a limousine company that I've been using for 20 years here. They have a rule for all their drivers, they cannot answer a phone call. You know, they have messages built into the phone: I'm currently with a client; therefore, I'll get to you afterwards. But they're connected to 300 other limousine companies around the world. So I'm their number one customer. I do about 150 trips because I've been driverless for 25 years. People say, have you ever thought about a driverless car? And I said, well, as far as me driving, I've been driverless for 25 years. It's either Babs or it's the limousine company because, first of all, I want someone who's good at driving the car and that's not me. But the interesting thing about it is that they're always 15 minutes early, everything is always clean, and Babs requests that there's no scents, you know, because she's very sensitive to smells.

But the owner, I don't see him very often, but I've seen him two or three times. But right on the dashboard, you can see in front of them, it's Dan Sullivan, five stars. It's got my name there. And I said, I noticed my name with five stars. What's that mean? "You're number one, Mr. Sullivan. We're always reminded when we have you that we have to give you our best service." So they have new drivers coming on, and the first thing they're talked about, we do that. And we're constant right during COVID. We were taking three or four trips a week, you know, when everybody else died, you know, the other limousine companies. And they did too. They got very restricted. But the whole thing, as the world becomes more technological, I think a premium on person-to-person interchange becomes more and more valuable in the marketplace.

Jeffrey Madoff: I absolutely agree, and I hadn't thought about it until just telling you that story a couple minutes ago. I still do it in terms of conversations, but not nearly like I used to. And that was fun for me that, you know, I would learn a bit about why this guy came from Afghanistan to the United States. And, you know, how did you learn your way around the city? And I mean, just all this kind of stuff. And, you know, wasn't always fascinating, but there was a human interaction that went on there. It was nice. And we have gotten away from that in so many different realms of our lives that I think has fueled the polarization that we have because we bring our own assumptions into something without regard for where the other person's coming from. And those little, what many people might think are meaningless interactions, whether it's with a clerk at a store or a waiter in a restaurant or the driver, that's part of being a human being and interacting with other people and learning how to build a bridge between you and them in order to do that. And I think that's just like what you're talking about at the very beginning, these little damages that happen and don't get fixed. It's kind of like that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I mean, sometimes it's quite big. In downtown Toronto, I mean, it's gotten very high because the condos are starting to blot out the sky, but right on the lake, on the harbor—we have a really good harbor in Toronto, and then it's Lake Ontario—the Westin is down there, and they have this huge, across the top, fluorescent "Westin." And one winter, the W was out for six months. And I said, I don't know what goes on in that hotel. Does anyone tell the manager or the general manager that the W is out at the top? "Estin," you know. But what's it tell you about the service of that hotel that they wouldn't correct a maintenance problem like that. They wouldn't correct it ... that day. I mean, if it's the Four Seasons, but they don't have that kind of sign, but they would correct it. And the Four Seasons has a very interesting technique. You know, and most of their staff are immigrants, the cleaning staff, the restaurant staff, and everything else. This is their foundational. This is a big job, to work for the Four Seasons is a big deal. But they have a rule, and this is the rule for everybody: every day you do your job and one other thing.

That's the rule. They have 40,000 employees worldwide and everybody, you do your job and one other thing. So what's the other thing? Your job is to clean the room, but you notice that one of the lights in the table lamp, the light is out. So immediately when you're finished that room, you contact maintenance or housekeeping or whatever it is that they contact and say, there's a light out. Well, it's not their job to check lights, but it's the one other thing for that day. And tomorrow, it's something else.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's great.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and what it does, it just creates total quality control with one rule. And they have another, the way they hire people, they're all done by jury. So everybody in any job in Four Seasons, it's done with a jury. There's six people on the jury, and every employee in that hotel is on potential jury duty. So let's say it's a cook, not the head chef, but just a cook, you know, in the kitchen, and he's on the jury, and they're hiring a new assistant general manager. He's being judged by that cook in the kitchen. Six of them. It's mixed. And there's two questions you have to ask: Would this person represent the culture of Four Seasons? In other words, would this person give a positive impact on anyone who's not part of the community when they come in? And the other thing is, would you enjoy working with this person? If they don't get six yeses, they don't hire the person. So they've got a rule that just guarantees quality of staff, and then they get, you know, do your job and one other thing. And the other thing is that if you're stopped by anyone who is from outside the hotel, and you're asked about where is such and such, you stop what you're doing and you actually take them and hand them off to the person they want to see. So, just three rules.

Jeffrey Madoff: I mean, I think that, you know, when you talk about the Westin, which becomes the Estin, that's your most public-facing…

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right?

Dan Sullivan: It's the thing that everybody sees.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: And it's wrong.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Which is kind of fascinating because you wouldn't think you'd have to wake somebody up to that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but every employee must see it every day.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, including the manager.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, the letters are 10 feet high at the top of the hotel. They're big, big red. They're not fluorescent, they're backlit. It was six months before they repaired it, and I said, I don't think I want to stay in that hotel.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's kind of fascinating because also management saw that every day they came to work. So let me ask you about this because this is something I was actually just talking to Margaret about this earlier when we had coffee this morning. We went to a new coffee place, and it used to be you'd go in and if you got some coffee to go, this was even true in the early days of Starbucks, but now, you know, the 15, 20, 25%, and the 20% is highlighted, so you do that. I'm thinking, all I'm getting is a cup of coffee, and all you're doing is handing it to me. Now, I don't blame the person, but to me, for the management, pay your people enough money so that's not what they're dependent on. It's not like, you know, with a waiter or waitress, you're spending an hour and a half with them. And it's a whole different kind of transaction, right? When you go into a store and you pay your five bucks for a cup of coffee, to me, that's kind of enough. But I leave a tip because I feel a certain social pressure to do so. But I think that that's become now a fixture. Used to just be-

Dan Sullivan: Looks like a tax.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: It's your tax for coming into the store.

Jeffrey Madoff: But isn't it weird?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, no, I see it all over the place. Now, I've got a different attitude. Generally, I'm suspicious of charities. Okay, I'm suspicious of them because how do you have any information whatsoever that the money that you're giving to a charity is actually going to the cause that they're advertising? Okay. I had a really torturous relationship for about two years with the Canadian Red Cross. So two young guys, you know, they knock on the door and both presentable and very well spoken. And they said they were Canadian Red Cross. And so I said, sure. And I reached for my billfold and they says, well, we can't take cash. I said, okay. And they said, so we need a credit card. But before that, you have to talk on the phone to our manager. So, this is feeling more and more like work. I was reading a book and having a drink and now I'm working for two young guys from the Red Cross. I'm feeling... And say, geez, I'm not getting paid for this. You know, anyway.

Jeffrey Madoff: Actually, you're trying to pay them for it.

Dan Sullivan: I'm trying to pay them, but they won't accept my payment in the form that I would like to give them. I find cash still fairly significant. It's legal tender. You know, it's still legal tender to give someone cash. And I'm usually quite good about it as long as it's not after six o'clock at night. I don't like having people knocking on my door after six. So I get on and they said, Mr. Sullivan, yes, I want to check. And the big thing is, it's very dangerous because I don't know that the person I'm talking to, and I'm giving them my credit card number. So it goes on, it's for a year, but after a year, they don't recognize that it was for a year, and they keep deducting from my credit card. So I try to get a hold of them, and it's impossible to actually talk to the person who will actually say, well, I'd like to stop these payments.

Now, meanwhile, I've gotten no information whatsoever from the Canadian Red Cross for what I'm doing. And I have no idea that the money I'm giving is going to the purpose that the young men were advertising. So I talked to the bank, and I said, I'd like to stop my cash. And they said, it's almost impossible with the Canadian Red Cross to cut them off, so what we'd recommend is that you just get a new credit card number. I did, and then they start pestering me about why I cut them off, but they never gave me any information. They never kept me in touch. And so after COVID, I decided I'm just going to give all my charity money in tips. Because you're a little closer to the human who might actually be using the money.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's really interesting because the nature of compensation for a transaction. It used to be only at a restaurant, I guess I don't golf, but you know, you tip your caddy and of course you tip the waitstaff. But now that's gone to many, many areas of life. And I've even online gotten, you know, would you like to include a tip, which just, for what? For what? But I do think that... Funny thing is, it's concurrent, kind of what you're saying, it's concurrent with the lack of customer service you get.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, you're paying more for less.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and that's true both figuratively and literally. That's correct. So what do you define, and I've had this discussion actually with Ralph Lauren, talking about luxury markets, and what is it, how do you define luxury? You know, I mean, you stay at a great hotel, the Four Seasons, you eat at very good restaurants. At least you used to shop with that man who became a friend of yours who owned the best men's shop in Canada.

Dan Sullivan: Harry Rosen.

Jeffrey Madoff: And what do you consider luxury, and how do you differentiate what you are willing to pay for, as opposed to feeling taken advantage of?

Dan Sullivan: I think our brain goes in different directions of considering luxury. It's, you're comparing your present self to a past self and what you would have spent money on in the past or, you know, what you could do. So when we fly, we always fly business class or whatever the highest class is. Because you get to go on the plane first. And we always get in line first. So they have the two lines, you know, area one, two, and then area, you know, at the back. So Babs and I are usually always the first two people on the plane, and we get there and we get comfortable and everything else. And they take care of you, you know, cause the number of business class. But we don't travel that much, so it's, I mean, if I was doing three or four flights a week, it wouldn't make any difference. I'm just gonna pay for it, you know? And the other thing is that I do a little question with my clients, and I said, how many of you believe in the afterlife here? You believe that there's another world? And nature of my clients, most of them do. I says, well, how many of you believe that you get to go to heaven for going economy class on this planet?

Jeffrey Madoff: I'm sorry, you get to go to heaven for?

Dan Sullivan: Doing everything economy class. I mean, is that something that earns you? And I said, since it doesn't get you to heaven, why are you doing economy class in this world? But you're selective about that. There's a bit of discernment because some luxury is just very, very expensive. But some luxury is real luxury. I mean, Harry Rosen, if you got a suit from him, that suit's good for 25 years. I mean, it's bespoke, you know, it's handmade, and the fabrics are just fantastic. I have 15-year-old suits that are like new. You know, and he says men can get away with this because men aren't about fashion; men are about style. For example, you have a very definite style, you know, and when I met you 15 years ago, you had a very definite style, and you still have that style. It's a particular Jeff Madoff style. You always present yourself extremely well, and you have a style that you think goes along with that, and who you are, and who you hang out with. See, men can get away with that. Women, it's every quarter. And Harry Rosen tried to go into women's fashion, and he said, women aren't looking for a business suit. You know, they're looking for whatever keeps them in the know and keeps them in fashion. But the other thing is, it has a lot to do with my family. And my family never do anything luxuriously. And I just, right from childhood, said, when I get enough money, this is how I'm gonna live. And I've lived that way for a long time.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you bring up something interesting and it triggered a thought to me. With style, you know, what is style? I mean, I think style is a personal projection of who you are. You know, when I think of iconic style, I think of Audrey Hepburn. You know, Cary Grant. These people that always projected this great air about them before they even said anything in the way that they presented. And with fashion, you have to make sure that you are wearing the fashion, the fashion's not wearing you. You know, because it's about the frame that you put yourself in, as opposed to, which can happen with a lot of fashion, the look that overwhelms you. So, however eclectic, whatever that is, I think of someone like the writer Tom Wolfe, he always wore those white suits, you know, and he had his look, and that was his style and so on.

But what that triggered in me is I thought about casual Fridays, which I think was one of the worst ideas businesses ever undertook. Because what had started happening was, and this is like, you know, the flaw or the scratch or the graffiti or something on the wall in the bathroom, or the W being burnt out at the Westin or whatever, is I believe that when things got more and more casual, and now it's to the point that you can go to the theater on Broadway and people are in Bermuda shorts and flip flops and a t-shirt, and somehow to me, that takes away from the experience. And that I think that these kinds of erosions that we go from tolerating to them being the rule of the day, I think diminish an aspect of life that we don't understand. As Joni Mitchell said, you don't know what you got till it's gone. And how do you feel about it?

Dan Sullivan: We both grew up, you know, we became aware of what it means to be an adult in the 1950s, both of us. You know, and a lot of it was determined by people's response to the movies. But people dressed well, you know, they dressed well. You know, they're generally, you know, if it was anywhere not completely casual, it was a suit and tie. You know, you wore a jacket or a tie, but you wore a tie. You know, that was very, very influenced. Also, Hollywood became really big during the 1930s and '40s. But the U.S. in that time was going through a tremendous, what I would say, design phase where lots of things were beautiful. The cars were beautiful. The planes were beautiful. Chrysler building in New York, that was late '20s. But they were very, very influenced by the style of the movie stars and the wealthy people dressed well. And there was a certain conformity to it, but there was a lot of variation that individuals would have a particular style. Cary Grant never wore anything that wasn't stylish.

But going back to Harry Rosen, he said, "The first thing we have to establish with you, Dan, is your style confidence." I said, "So what's my style confidence?" And he says, "We have to explore that. We have to explore that because we have to find out where you are and what you do." For example, my style confidence has changed enormously from pre-COVID to after COVID. Because you don't wear a suit and tie on Zoom. I don't. And, quite frankly, none of my clients do. So I dress according to what my clients. People come to the workshop and they have a suit and tie. I'll quietly tell them by the first break, lose the tie. You can have the jacket, you can have the shirt, but put something between you and other people who aren't wearing a tie. So lose the tie, you know. And some of them don't take seriously. And I said, I mean this seriously. I mean this seriously. You're setting yourself apart, but it requires teamwork. And the way you're dressing is interfering with the teamwork of the workshop.

Now, everybody else is dressed well. They have nice clothes on. It's good fabrics and everything designed. So appropriateness has a lot to do with what style. Is it appropriate to the situation? This is where I see the great breakdown in society today, that how they're dressed is not appropriate to what's going on. They're trying to make how they're dressing bigger than what's going on. So it's kind of, I don't really care how you think things should go here, this is the way I'm going to present. It's conformity posing as individualism. They're conforming to a network that's not there that night. They're conforming to how people in their network kind of undermine the value of public experiences, mainly.

I went deeper with Harry Rosen, and I said, how do you know you have style confidence? He said, you're at a big gathering where everybody is dressed up, and you're the only one in the room who isn't thinking about how you're dressed. You just have a confidence that you're well dressed. And he says, that's style confidence. So for example, he had a billfold that was at least 50 years old. It was almost falling apart. And he just superbly dressed. Harry was always superbly dressed. But then he'd take his billfold out. And I said, why do you have that old billfold? And he said, I like it. I like it. I mean, if you have a problem with my billfold, then you have a problem. But the other thing is, on his jackets, he always left one button. You know, you have the cuff buttons? And he always had one button. And he said, that's part of my style. I like doing that, you know. So he said that it shouldn't be uniform or conforming, your style confidence. It should just be, you're not thinking about how you're dressed.

Jeffrey Madoff: And that's interesting. Two things come to mind. One is, I'm inevitably in situations where somebody would say to me, oh, that's a really nice jacket. And I'd say thank you. And say, but I could never pull anything off like that. And so, what do you mean? You couldn't pull anything off? No, I mean, you know, it's really, I think it's really cool, but I could never pull that off. And I'm thinking, well, I put it on and I was comfortable in it. And I don't think about, can I pull this off or not? It's just, you know, to me, like that's fashion is fun. So I never worried about... I know I have good taste and I was never worried about that.

Which, by the way, carries over with this producer I was meeting in terms of theater. And we were talking about the play, and we were talking about the story, and he said, well, I know it's going to be good. I said, oh, really? How do you know? And he said, you have good taste. So, I know you well enough to know you have good taste. It's going to look good and be good. Which was nice to hear. Then I think of the surprise. And this is Ralph Lauren. Ralph showed up at this big event, fashion event, and he was wearing a tuxedo, you know, the bow tie and all that, and jeans and cowboy boots. And it totally worked and was really cool. And he has the confidence that he can carry that look. And nobody came up and said, what are you doing wearing blue jeans with a tuxedo jacket? And that became a look. And because he had great taste, not good taste, great taste, and he had the confidence of whatever he put on, that he could pull that off, so to speak.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. But there were situations where he wouldn't do that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right.

Dan Sullivan: He wouldn't go to the White House that way.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, he wouldn't go to the White House that way. When he got his Lifetime Achievement Award at Lincoln Center that was given to him by Audrey Hepburn, no, he wore one of his tuxedos.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And it's appropriate.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's correct.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I have credibility rules. It might be interesting talking about it on another podcast. But I said, you know, you can avoid about 95 percent of the troubles that people get in by following five rules. Number one, show up on time. Second one is, do what you say. Number three is, finish what you start. Number four, say please and thank you. And number five is, be appropriate. So stand out as a person by showing up on time, doing what you say you're going to do, finish what you start, say please and thank you. And appropriate. That's how you stand out. And I have discussions with people. "Well, that's just being conformist." And I said, yeah, but when you don't do those things, you don't get a second call. Doors just automatically close. And you're never going to know what you did not to have an open door. But if you show up on time, do what you say, finish what you start, say please and thank you, and be appropriate, the doors are gonna be wide open.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and it's really interesting because, again, now, you know, we have our all-encompassing title for our podcast, Anything And Everything, which, you know, that was a brilliant name you came up with because we can never violate the title. Everything we say is appropriate as a result. But when you talk about those things, show up on time, do what you say, finish what you start, say please and thank you, and be appropriate, that again is like the broken windows in the warehouse. That's, you know, showing up at a Broadway show in a T-shirt and Bermudas and flip flops. And if somebody says, well, that's, you're being a conformist, let's wait, what is it that I'm conforming to that seems to give you a problem? Last night, Margaret and I watched Zelig, which I had not seen since it came out.

Dan Sullivan: Great movie.

Jeffrey Madoff: Brilliant. Well executed. But it's absolutely brilliant. And his whole psychosis was he wanted people to like him. So he went to the extreme of complete physical transformation to fit in with whatever group he was with.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it was amusing because of all the historical characters. I mean, it was like Tom Hanks in Forrest Gump. You know, people are picking up on Woody Allen there, but, you know, it's the same thing. You know, he's in famous places. Lindbergh lands and he's right next to Lindbergh. He's there with Hitler. You know, I mean. Yeah, but nobody notices that he's there, you know, he just… He wanted to become so agreeable that he disappeared.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And that's, I think, that's really brilliant because the thing is, what are you conforming to? And one of the things to me is, look who's applauding before you take a bow. You know, there are certain people that you don't want compliments from.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, yeah. But the big thing is that, you know, for example, I've put rules out because I get a lot of requests to be a speaker more and more, especially because of the books. You know, people have conferences or they have meetings and they want me to speak. And so I wasn't giving a set of rules to my team who are generally interacting with the people who want to. So I said, from now on, I don't give any speeches at all. I said, for the rest of my life, I'm not going to give any speeches. But I will coach a thinking tool. If people want me to come, I'll coach a thinking tool. And this is where we put out the materials for everybody, and I take them through a thinking tool. And part of the going through the thinking tool, they're going to get what they have down on paper and then they're going to talk to the people next to them or behind them or in front of them. And you'll see that in Nashville. I have the opening speech, but it's not a speech. I just have a thinking tool. You have 300 people in the room. For most of them, they're meeting somebody else for the first time. And some of the people there are going to be a spouse, they're going to be other people besides someone who's in the Program. So in the first hour, I just get everybody in the same program.

The other thing is, I will only have a panel where I'm the head of the panel. I will not be on somebody else's panel. And the other thing is, I won't travel for somebody else's event. If they want me to appear on Zoom, I'll do Zoom, but I won't actually get on a plane and go to their event. And some of our marketing people say, you know, there's big opportunities. There's now, you know, crowds of 2,000 that you'd go there. You know, it's just an hour they want you for. And I said, it's not an hour; it's three days they want me for. I got to go there. I got to be there for a whole day, even though it's an hour, and then I've got a whole day to come back. And I said, if you're doing a good job of screening people correctly and we're getting really good leads, I can do a Zoom call and get more of an impact in two hours sitting in my basement than getting on a plane and going. I said, now, in the old days, it was very important for me to do this, but it's not important for me to do this anymore. You know, I don't want to be doing your work. Your work is to cultivate leads and do that. So the big thing is, and I don't know if you've noticed this as you get on in decades, there's things you would have done in your 40s that you won't do in your 70s.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, absolutely. Yeah. Some of that just comes from, I don't have to anymore.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And that's important.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes.

Dan Sullivan: I don't have to do this anymore.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, just having three books out there that are really good-selling books has brought us far, far more qualified traffic than we ever got by doing public events. And I think the world has changed too.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think so. But how do you think the world has changed?

Dan Sullivan: How do I think the world has changed? I think it's harder getting people's attention now than it was 30 years ago. You can't just phone somebody these days. You go through layers. And I think having a great reputation is much more than having great marketing.

Jeffrey Madoff: Go a little deeper.

Dan Sullivan: Well, word of mouth is a lot more powerful than, you know, fancy computer graphics.

Jeffrey Madoff: Totally, totally agree with you. The most primitive, you know, over the picket fence or in the cave or whatever, you know, the referral by someone you trust that you should see this, read this, try this, whatever, means more than all the marketing in the world, I think.

Dan Sullivan: Great people saying great things about you.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. That's the best marketing in the world.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. I think that's true, too. There's a word that we used a lot today, and I'd like to get your definition of it, and that is appropriate. What is the definition or how do you define appropriate?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think it relates to what is the context here and does it fit with the context? So I think it's contextually correct. And I think there's an enormous amount of content today, but there's less and less context. And that could be situation, it could be place, it could be purpose, you know, what's the purpose of this? It's like giving negative feedback at a funeral.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, they could have lived their life better.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. While everybody's saying nice things about this person, I'd like to give a different point of view here. It's not really appropriate. First, nobody cares what you think, and it's just not appropriate. In public settings, they each have a context, and there's an appropriateness about what you do as a participant in a public situation. But appropriateness, I haven't looked up the word, but you know when this is the right thing to be doing in this particular situation.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, it's the context. You're absolutely right. I'll throw out, by the way, something for the listeners that I would highly recommend. There's a short book written by George S. Trow. It actually started as an article. And it's called The Context of No Context. And it's absolutely brilliant. Because I think that context is everything.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, me too.

Jeffrey Madoff: You cannot understand things unless you place them in context. So what can be appropriate in one circumstance could even be destructive in another. So I think that being appropriate is completely dependent on context.

Dan Sullivan: Well, and you have to see things from other people's point of view.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: It's one of the biggest thing of knowing the context is understanding how other people are looking at the situation.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, especially if they are part of that situation. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: You know, the one thing that, you know, when we had our party in Chicago, we had the party after Personality and the first night when you were there. And I was really, really selective about who I invited. We had the before party or before dinner, and then we had the afterwards party and we went. They were closing down the restaurant. But the big thing was that I thought it was really important for you to get feedback from my friends who I had invited to that, that it would be good for you. It would just cap off a really good evening for you. It was a great show. I mean, the show was great and everything, but it might have been two weeks later and you say, what did your friends think? And so what I wanted to do is just set it up so that you could actually hear from them. And they had great things to say.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I'm very grateful for that.

Dan Sullivan: And your daughter was there, too, so that was important too, for your daughter to actually hear what other people are saying about her father's work.

Jeffrey Madoff: And fortunately, she didn't have to defend me, which was good.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, you were on pretty good behavior that night.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that was a wonderful evening in total. The dinner and then the play, then actually went back to the same restaurant and had dessert and a conversation. Yeah, it was good for me. It was great. And given the circumstance, in the context, these are people that you like, respect, that you thought it would be good for me to hear from, although you had no idea what they were going to say.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And the thing is that they were going on my recommendation that I think this is going to be a great play. So, and I wanted to hear it. I wanted to hear it. Some of them flew in from other places for the show and everything else. But every situation has its own context. And I think our upcoming book that you and I are writing together, Casting Not Hiring, casting is about context. Hiring has no context to it whatsoever.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Well, limited context. You're looking to fulfill a particular job profile, but you're not thinking in the wider context of the business. I agree. And it's also interesting because what's appropriate, and this is a thing that I'm looking forward to going into in the book. What's appropriate is Stanislavski, the great director and acting teacher from Russia, who was basically the godfather of the method that changed acting forever, talked about the given circumstances. And the given circumstances are the context, which define appropriate behavior in a given situation. So what I mean by that is, it's appropriate for Clark Kent to be running and shedding his clothes and then leaps out a window as Superman. But if you're doing some serious family drama, nobody's going to take off their clothes and jump out the window and fly. It's appropriate given the circumstances for Superman, but it's not for that. And every situation in that way defines someone's behavior in terms of what is or isn't appropriate. And so it's a fascinating discussion, I think, because it so clearly focuses the person on understanding the context and what their actions or reactions mean in that situation.

Dan Sullivan: And just to connect this back to previous things is, if you're charging luxury prices at a restaurant, it's inappropriate that you would ask people to scan it on their QR code what the menu is. You should have a nice menu. You should have a menu that matches the amount of money that they're paying for the food. In other words, the menu should be part of the pleasure.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Oh, absolutely. Absolutely.

Dan Sullivan: That's appropriate.

Jeffrey Madoff: My mom used to love this restaurant that was outside of Akron. And when the bread basket shows up with the individually wrapped pats of butter, you know, and I said, Mom, come on, you know better than this. This is not a good restaurant. Good restaurants don't have those kinds of buns in the basket. And they don't give you the individual wrapped slices of butter.

Dan Sullivan: The one thing, they used to give it to you. They don't even give it to you anymore.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's true too.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, that's another thing. We had a great restaurant, and we still go to it. They don't do this anymore. But they had a very small restaurant, and they discovered that if they hung the bread basket from the ceiling, it was in a basket, it had a line, and you would unhook it, and then the bread basket would come down. And they had this wonderful dark bread. The butter was on the table, so they didn't put the butter in the basket. You shouldn't put the bread and the butter in the same basket. That's not appropriate. Anyway, but I talked to the owners because they had a very, very narrow, you know, they could fit maybe 40 people in the restaurant.

And they said that they discovered that having the baskets on the table meant they had four fewer tables. It took up room, having the bread. So what they did, and it became very famous, the bread baskets from the ceiling, because it was artfully done. They were nice baskets, and the bread was fresh, but it was this dark brown, rye-ish type of bread. The butter was not hard. Sometimes in the little wrappers, the butter just came out of the freezer. That's not appropriate. You should be able to actually not have to work to cut the butter. But now they've got a much bigger restaurant. It's three times the size and they don't have to do that anymore. But they took something and they made it for cost savings, obviously, or for greater income. And they turned it into a thing that was very artfully done.

Who's the person that's going to handle the line, you know, to get the bread down? But that restaurant, I've been going for 44 years. It's a French restaurant. And French restaurants never have to change their menu. It's a bistro, you know, Le Select Bistro. But it's always been very, very good, and it's first class. I mean, it's impeccable. The upkeep of the restaurant is just impeccable, you know, and it's always really great. And in the luxury, they started off as more or less a neighborhood restaurant, and now they're into a luxury mode. But they sold about three years ago, and they had a new owner, and the value of the wine cellar was $12 million.

Jeffrey Madoff: Wow. Wow.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. They have an amazing menu. But you know, if things are appropriate, you don't think about cost. That's what I've noticed. Some people don't like it, but I've had two or three really, really great experiences at Daniel, the restaurant. What's it on 76? It's a, is it Fifth Avenue?

Jeffrey Madoff: I'm not sure. Daniel?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. It's a French restaurant in New York. I think it's at... I know where Park is, because Park goes up next to the park, so it's the next street over. What's the next street over?

Jeffrey Madoff: Depending if you're going east or west.

Dan Sullivan: It's above the Pierre and those hotels, and not too far up, but it's around 60. But it's very nice. But they let you know you have to wear a jacket. Men have to wear a jacket. But the food was great, service was great, very knowledgeable service and everything else. But I like things if they're charging you a lot of money, that they give you an idea they're using the money to keep things good.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and I think that what causes me to feel kind of ripped off is when the expectation that is set by the place is somehow not achieved. In a way, everything we've been talking about, and I think it applies to personal behavior, and it applies to business, is the kind of death by a thousand cuts. It started us off by talking about how you can see these telltale signs that are indicative of a business that's in trouble. And I think that someone who drinks too much and is loud at a party and says insulting things is not being appropriate. And you can tell they're going haywire just like a business we're referring to. So I think that the metrics we've set up and your five statements about show up on time, do what you say, finish what you start, say please and thank you, and be appropriate... That's true for individuals, and it's also true for businesses. If you set out the promise, this is a good restaurant, then you have to deliver on that promise in every single thing you do. And that's from how the wait staff is trained to interact with you, to making sure that if there is something that is messed up, that it's taken care of quickly.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Another indication that things aren't good is where they have a printed card—this could be in any kind of establishment—these are our principles of customer service. You know if they have to print up their principles of customer service, they don't have good customer service.

Jeffrey Madoff: And service, by the way, as the customer is something that you receive. So they're the ones that have to understand it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything And Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

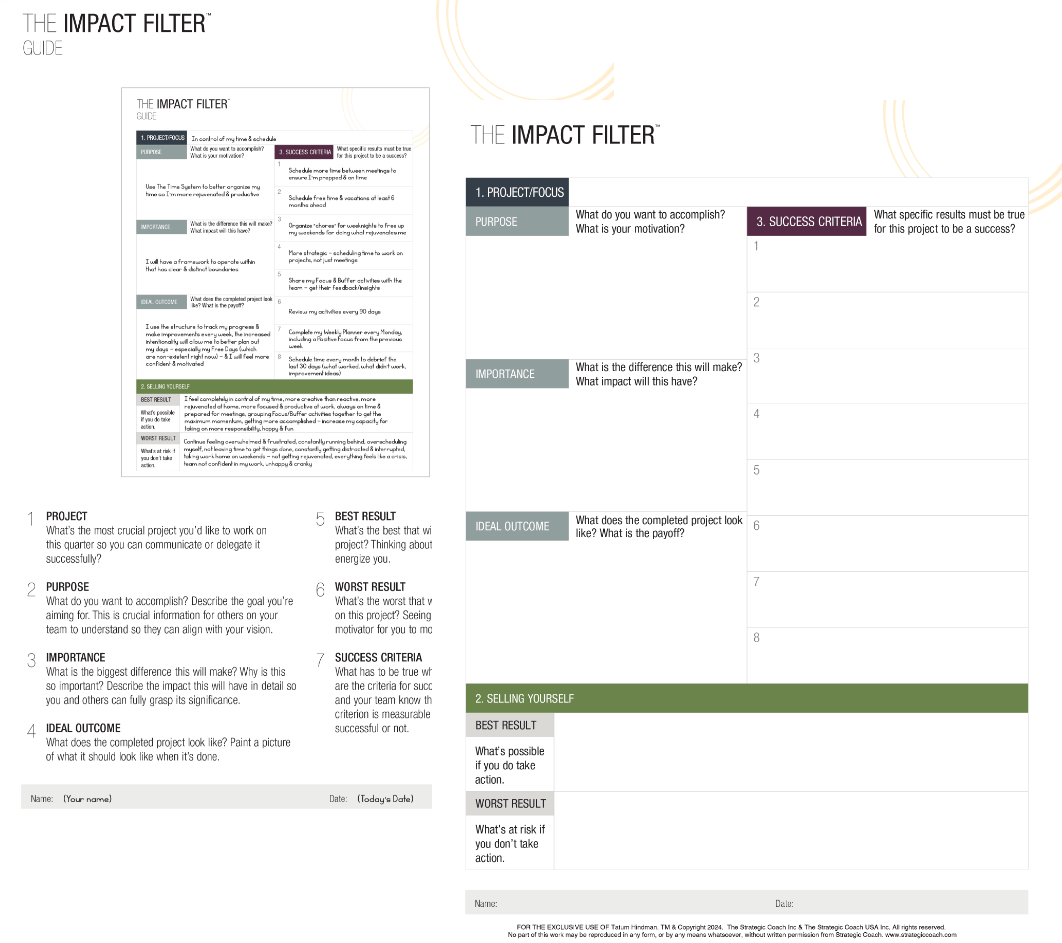

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.