Why Retro Is Making A Comeback In A High-Tech World

August 27, 2024

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff and Dan Sullivan explore the limitations of AI, debunking the myth of technological singularity. They discuss Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, Apple's controversial iPad ad, and the evolving global economy. The conversation challenges common assumptions about AI's potential to surpass human intelligence, offering valuable insights for any entrepreneur navigating the tech landscape.

Show Notes:

- Gödel's incompleteness theorem suggests that technology, as a subset of humanity, cannot surpass human intelligence.

- Technological singularity, predicted for 2029, is unlikely to happen because speed and information retrieval don't equate to true intelligence or creative thinking.

- Military research, gaming, and adult entertainment have been major drivers of technological advancement.

- Apple's recent iPad ad controversy highlights shifting consumer attitudes toward technology.

- Tech companies may be facing market saturation, challenging the constant push for new products.

- The revival of retro trends and vintage items reflects a broader cultural shift toward appreciating the past and seeking uniqueness.

- There's a growing disconnect between human creativity and the tech industry's approach to content creation and distribution.

- Tech giants like Apple have transitioned from being rebels against the establishment to becoming the establishment themselves.

- Tech companies should focus on balancing technical specifications with human-centric storytelling in their marketing strategies.

- AI excels at pattern recognition but falls short in replicating human-like thinking and creativity.

- Entrepreneurs should consider the limitations of AI when integrating it into their business strategies.

- Understanding the distinction between technological capabilities and human intelligence is crucial for innovation.

Resources:

Personality: The Lloyd Price Musical

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Book: You Are Not A Computer by Dan Sullivan

Book: Your Attention: Your Property by Dan Sullivan

Video: “Crush!” (iPad Pro ad)

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: Hi, everybody. It's a Sunday afternoon, and I'm having my Sunday afternoon conversation with Jeff Madoff, who's in New York, and he is a father, so he's legitimate. I'm a pretender. So anyway, Jeff, some interesting articles recently about technology, especially one that was triggered by a unusual mistake. I say unusual because usually Apple is better than this, but they came out with a commercial for the iPad, the new iPad, I guess it's a new iPad, and it shows a I guess it's a car crusher or something like that, that crushes existing technology. And they've said all the technologies of human creativity are now being crushed. And in its place is the iPad. And it really didn't work. This commercial really didn't work, you know. And I think it didn't bring up all sorts of questions about the commercial. It brought up all sorts of questions about Apple, you know, and what's happening at Apple that this got through all the safety checks.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and I think it raises questions about where we're at as a culture now, too, because technology has been such a driver of global economy, and there's a transition going on. But before we started recording, Dan and I usually talk for, you know, 30 minutes before we even start recording. Listening up. Yeah, just, you know, stretching, doing vocal exercises, all of that. And you were talking about humanity and subsets. I'd love to lead in that way, because that was very interesting.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, there's an interesting mathematical formula that was created by, I think he was Austrian, an Austrian mathematician, 1930s, it's called the incompleteness theory, and the grader is a mathematician by the name of Kurt Gödel, G-O-E-D-E-L. And Einstein said that he thought that he was the foremost mathematician of the 20th century and they actually worked together at Princeton, they ended up at Princeton together. Both came over before the Second World War. But he came up with an incompleteness theorem which in layman's terms says you can't be part of a system and understand the system that you're in. That's how it gets translated. And he was talking about how it's led to a discussion about technology and especially about intelligent technology, which we're in the throes of since OpenAI came out with ChatGPT. And there's always been this theme in the technological world that at a certain point, the increase of speed of technology, the computing power of technology is going to exceed human intelligence. And I've always personally been very, very skeptical about this notion. And my thing, using Gödel's mathematics, that all technology is created by humans, that we know of, that we use, is created by humans, and therefore, technology is subordinate to humanity, and therefore, according to Gödel's theory, that you can't be a creation of humanity and understand the creator. You know, essentially, that's a form of mathematics called set theory. You have the set and then you have the subsets and everything that humanity has created is a subset of the set called humanity. So my belief is that it's impossible for a technology created by human beings to actually understand or surpass human thinking.

Jeffrey Madoff: And it's interesting because it makes me think of one of the phrases that's used a lot in self-help and direct marketing, which is, if you're inside the jar, you can't read the label.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, that's a subset of Gödel and mathematics. And mason jars. Yeah, mason jars. Yeah, I'm not sure what prompts this line of thinking. I don't know about you, but I found that I only have direct access to one human being for the last 80 years, and it's a full-time job, so I don't know. I mean, I think it falls under the category of anything and everything, but we've just never really talked about this particular thought that's out there, it's called the singularity. And a man by the name of Ray Kurzweil is its foremost proponent. And he's predicting 2029, the speed of technology, the thinking capability of technology will be so great that it surpasses human intelligence. I remember Peter Diamandis says, what do you think it's gonna be like when that happens? I said, it'll just be another day.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, just like the change to the 2000s. I forget what that was now called, but you know. Y2K. Right, right, right.

Dan Sullivan: Will anyone notice, you know? Speed is sort of magical and it's also misleading. I mean, my thermostat in my house is obviously smarter than I am about, you know, adjusting temperature throughout the day. There's lots of technologies that are way faster than us. But is that thinking, you know, is that thinking?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's what I was going to ask. And I do want to give just a footnote to any of those who are interested in Gödel's theories, that there is a book that was very popular. I think it was probably in the ‘80s. I don't remember the word, but Gödel, Escher, Bach, which was very popular and a really interesting book to read. I think it's a really interesting question because, first of all, If you set a deadline for something, it gives you all the way up to that deadline to sell something that'll counteract it, you know, and market something that'll counteract it. And then there's the shift from 1999 to 2000 and everybody's sort of waiting and nothing happens. So, you know, it's, so then, well, 2029, that's when it's happening.

Dan Sullivan: I remember everybody was keen about the New Year celebrations in Australia when Y2K happened. They had worldwide coverage of the fireworks in Sydney Harbour because Sydney is really the first major metropolitan area that encounters the new day. Right. Seemed to go fine, and then got to Tokyo, and Tokyo was fine, and by three o'clock in the morning, you know, you were, yeah, I think things are going to be okay.

Jeffrey Madoff: It seems to be, there's a tendency to be hyperbolic about any major shift that seems to be happening. And, you know, somehow we get through leap year, you know, and nothing really happens. And a person who was born on leap year, my niece was, she ages like the rest of us.

Dan Sullivan: It's kind of… He doesn't get as many gifts, but… That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. She's easy. That's right. That's right. Feels cheated, but, you know. You know, it's with Apple, what I think was so interesting with the commercial, I think it was called “Crush!”. Advertising and marketing is always trying to sell us something. That's, you know, the great Shakespearean question, modified a bit, which is to buy or not to buy. You know, I think that the question that's come up as of late is why buy? Like people don't feel the compelling reason to buy a new phone every 12 to 18 months. And what can I really offer? How many different lenses do you need on your phone camera? You know, all of this different stuff.

And I think that there was a great period of innovation. That innovation to many was seductive. They wanted to keep up to date on the new releases of the new iPhone. People that would line up around the block for the new iPhone, I'm willing to bet that they all had functioning phones. So why they'd want to sleep outdoors other than be able to say to their friends, yeah, I was on, did you see me on the news? They took pictures on the Apple store on Fifth Avenue and we're all around the block. But everybody had a phone that worked.

And I think that the compelling reason to buy things has shifted and technology has shifted. And this is with Apple, it's with Microsoft, it's with many of the major companies. Google is AI. And now there's all kinds of people out there promoting themselves as AI experts. Here's how to use AI, supercharge your business. And I have the same question that you have. which is speed is one thing, but speed doesn't define intelligence. In computers, it's about retrieval time. So I think that it's really interesting to start looking at why do we buy and when something is offered like this, this new iPad that shows the destruction of all of the current tools, you see paint being squashed and typewriter being squashed and all kinds of things, an artist's wooden figure being squashed, all of these things. And then Apple tells you it's the thinnest iPad yet. And I'm sure just like me, you've heard millions of people saying, that goddamn fat iPad, it's way too clunky. You know, that was not the case. And it played into, to your point, what were they thinking, played into all of the fears and insecurities that people have about AI, that it's going to take over all these things.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but who's scared? I mean, who's really scared? I think the technology people are. I mean, the greatest fear that if you're in the technology business, because you're getting people to spend present money on future possibility, you know, what if people just aren't into it anymore? I mean, what happens to their stock price? What happens to their valuation? But I've got a sense that we're in a bit of a pause right now, because you used a word before, globalization. You used the global market. There's a whole set of books written by a man by the name of Peter Zion. He's a practitioner of geopolitics, and there aren't many of them around anymore. I came across him in 2014, and he wrote a book on how the U.S. had become the superpower in the world. And he said it was not intentional. The Americans never intended this. It's just that everybody else was either destroyed or they quit.

You know, in 1945, the Second World War ends and the U.S. economy was half the global GDP. America had half of it. You know, it's about 25 percent. I think they're 26 percent now because everybody rebuilt and everybody got back into the game. And the U.S., you know, going back to Washington, he resigned after two terms. He resigned and that set a precedent that most presidents stuck to. And he said the biggest danger that America has is getting involved in global affairs, getting involved in the troubles of other countries. You know, we got this big continent and we should be able to make do with what we have. And America has always had a disinterest in the rest of the world.

But it's a big place. It's 3,000 miles across. Essentially, the states are like countries. Each state is a substantial economic unit. And the U.S. did a deal, which was done in New Hampshire at Bretton Woods in 1944. And they did a deal with all the Allied countries during the Second World War, where they said, look, we got to rebuild the whole global economy. So here's what we're willing to do is that first of all, the dollar is going to be the currency of exchange for everybody. Everything we're talking about here is going to be in U.S. dollars because we have the only economy that can back up the currency. And we'll lend massively. We can lend you enormous amounts of money. And you rebuild your economy and you can industrialize and either regain where you were or build from new, and you can ship your stuff and the U.S. Navy will guarantee the waterways, and you can sell into the United States and there won't be any tariffs. But we're doing this because we don't want to go to war with the Soviets in Europe. So we're going to ask you from a military standpoint to be between us and the Soviets, you know, so it wasn't done for economic reasons. It was done for security reasons because Americans don't like seeing their taxpayers coming back in coffins.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yes, but I would push back a bit and say that it is also for economic reasons, because what ends up happening, and I don't think Washington could have anticipated it, is a global economy, and the dependencies that are a result of that, you know, whether it's Middle Eastern oil or whether it was after World War II for a while, inexpensive goods, cheap goods. I mean, made in Japan used to mean cheap. And then like with Sony, that was started with government money and rebuilding Japan, to the younger listeners, they may not realize this, but Sony was the Apple of its day. Best design stuff, really cool, had a visionary Akira Morita who ran it. So it's much more lucrative to deal with a global economy. So you also, you're correct about the tax breaks. You also don't want to kill your customers.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Especially if there's a lot of them. The one thing that you point out though, that even at the height of the global economy, America didn't have much to do with it. The foreign trade only represents a little bit more than 10% of the U.S. economy. It's mostly Americans creating things and selling it to other Americans, because it's the greatest consumer market ever created is the American, and everybody wants to be in on that consumer market. I'm only saying this because this was all premised on the existence of the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union collapsed, America said, okay, that's kind of taken care of, and everybody had such a sweet deal. I never saw a major historical event happen, like the collapse of land-wise the biggest empire in the history of the world, and it just collapsed. I mean, if they had asked permission, can we collapse now? Nobody would have given them permission, you know. And the reason was that deals that supported the global economy were so sweet that nobody wanted to know everything changed, but the American taxpayers noticed it because they were paying a lot for the support of this global structure, okay? I'm only positioning this back to the beginning of our discussion today, is that this is when the high-tech world took off. It was in the ‘70s and ‘80s that the high-tech, and most of the really inventive stuff really happened in the ‘70s and ‘80s. I mean, the Internet appears in the early ‘90s, but the Internet had been a military research network for 15 years. ARPANET had been there before. And, you know, the integrated circuit had been created in the ‘60s and everything. It just got to the consumer level in the ‘70s and ‘80s. But all the technology really was already there.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, and lots of it that was driven in the technology pushes forward in World War II.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and ongoing military. The military has always been a big part. Yeah, I mean, there's an organization called DARPA, which is a major, major innovator of technology. Nobody really knows about it. But, you know, the way technology advances, I heard this, somebody say, there's three things where technology advances very quickly. One of them is weapons. The second one is games, and the third one is porn.

Jeffrey Madoff: And having been in the video business for as long as I've been in it, porn was one of the biggest innovators. They created the video jukeboxes. A lot of those innovations in video and home video and video rentals and all of that stuff that even led to Netflix. I mean, all of that stuff started, you're right, in porn. And the interesting thing is that the games, the vast majority are some form of Warcraft, you know, which is also kind of an interesting thing.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's the biggest participation sport in the world is online gaming. It's in the billions, the number of people who in a year will engage in some sort of video game online. But I mean, to make simple our discussion here, what if the tech companies are encountering a possibility that there aren't any more new customers for new things?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I'd like to get to that too, because I think that's a fascinating discussion, because people have to have a reason to buy, right? And if you've already got X, you don't need to buy X again. And, you know, there's been a cycle be it the new phones or the new iPad or whatever, at a certain point, which has happened with the phones already, it's incremental. It's not a major wave of innovation anymore. So I wonder what was Apple thinking when, you know, they don't make snap decisions. It's not a stupid company. And how was that idea pitched internally? And what were they telling us in that commercial? And why would they expect us to buy what they were selling?

And by the way, Apple pulled that commercial almost immediately. There was so much negative blowback. And the negative blowback also spills over into AI, where there was Scarlett Johansson saying, no, you cannot use my name. And Blankman Freed called her up to try to say, well, you know, we'll license the sound of your voice. And she said, no. So I think there is a battle which is set up by business about the technology versus the humanity. And how do we protect the creators who are the backbone of new things? And I'll toss one other thing, because I'd love to hear your answer, is we talked about speed. AI is incredible because computers are incredible in terms of the speed of information retrieval, pattern recognition, but thinking, not so sure. Pattern recognition isn't thinking, it's recognition of recurring patterns. So how do you define intelligence?

Dan Sullivan: Well, first of all, it's not information processing. Because that's the contention of the singularity people, that the human brain is an information processor. Computers are information processors. And the speed of computing is advancing very, very quickly, but human processing isn't any different than it was with the Greeks. It's probably not really advanced that much. Biologically, I don't think we've improved all that much as thinkers. Therefore, at a certain point, the speed of computing will be faster, and it will involve all information retrieval on the planet, and therefore, it would be artificial intelligence will be superior to human intelligence. It all hangs and falls on that contention that we're information processors.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which isn't the case.

Dan Sullivan: If you talk to a neuroscientist … we're terrible information processors.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, we're terrible information processors, but that's also even not what our brain really does. It does some of that from just survival evolution. But it's really interesting because intelligence is something else. It's not the speed of retrieval. Speed of retrieval is speed. But do we understand anything more as a result of that? And who's serving what? You know, New York Times has sued Microsoft. There's been a number of publications and creative individuals that have sued for the misappropriation of their information that's being used to create what happens. What's mistaken for intelligence in AI is generative and predictability. That's not intelligence. That's just saying this pattern leads to this outcome, but its ability to predict is not very good. And you would think, by the way, it's always amazed me with Wall Street, is you would think all those fractions and all that information that there's got to be somebody who can always unlock the Rosetta Stone of investing, which is just not the case.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's like the final scene in the Lehman Trilogy. Read all the numbers, he's just fixated with data. And it's not even customers, it's just data. You know, you're just making your decision on data. Yeah, well, I wrote one of my small quarterly books. The title of it is, You Are Not A Computer. What I say in there is that we're meaning makers. We create new meaning. And I mean, the most powerful structure that has evolved with humans over hundreds of thousands of years, wherever you think the starting point is that we're distinctly different entity on the planet, is the story. The story is the most powerful cultural structure that there is. We grade our interest in how good the story is. And I don't think stories are information processing. I think stories are the raw materials coming from someplace else.

Jeffrey Madoff: I agree.

Dan Sullivan: That's not information retrieval.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And so you can establish the patterns of a story. That doesn't mean that you can then tell a good story. And so you might understand that, but what is it that makes somebody cry? What is it that makes somebody laugh? What is it that surprises somebody, that scares somebody? All of these things that are essential parts of great stories. In other words, people have to feel something. You don't feel something for data. You have to feel something as a result. And I think it's been already fairly established, because there was, in advertising and marketing, there is a real subservience to the god of big data, which just hasn't proven to be the panacea for business, which is, I think, quite interesting.

Dan Sullivan: Where have you encountered that in the marketing world, where it was almost like a new religion?

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, yeah. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, where have you seen that?

Jeffrey Madoff: I have seen it, whether it's companies that are determining what sells and therefore what they should make in the future. So the data tells them that people are buying this kind of thing, which never lasts because public taste is fickle and you don't know when it's going to pivot off to something else. You have no idea. In book sales, book sales is the same thing and the categories and whatever. In doing the play, when I send you out the update for our next step with Personality in London, it's the same thing. There's certain things that there isn't any data, and then there's a lot of things what they have, but it's not a full picture at all in terms of, well, who's buying tickets, And one of the problems I have with that is when the claims are made about what the data says, and I said, well, if you went to McDonald's, you would find that nobody eats lobster. Why? Because it's not offered there. So their data is going to show them that basically there's no market for lobster. So where are you harvesting your information from? What are the questions that you're asking? In AI, it's all about the prompts in order to get anything, and it's still you know, still pretty rudimentary. And the consistency is not very high at this point. Will that change? I'm sure it will.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, and the other thing is, when you finally interface with a human being, who's doing the interpreting of the data?

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: Because they're taking the data and creating meaning out of it. That's a human component. And humans, you know, there's good guessers and bad guessers. There's good bettors and bad bettors.

Jeffrey Madoff: And there's also the biases of programmers. So facial recognition, there have been now a number of lawsuits about this. The identification rate being accurate when it's identifying Caucasians is like in the low 80th percentile, something like that. For Asian and people of color, it's in the low 30th percentile. It's programmer bias. Most of the programmers are white males. And then people extrapolate the information from that, and it's just not accurate. So what questions are being asked, and as you said, so what's the interpretation based on? And what's the universe that that's being drawn from?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. So let's go back to the Apple example with “Crush!”. Something got crushed. You've got more of a feel for what happens behind closed doors in big companies than I do, because I've been strictly entrepreneurially-owned businesses for the last 50 years. That's not really a realm of humanity that I really have much insight into. But they were picking up on some sort of data. You know, it's not just Apple, it's whoever the advertising agencies are, the production companies that they're dealing. But there must have been a consensus at a certain point that, you know what, I have a feeling it was kind of like Steve Jobs envy that, remember the 1984 video that they did?

Jeffrey Madoff: When they brought out the Mac with a woman throwing the hammer at the screen.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And it was the face of Big Brother from 1984, the George Orwell novel that had been created into a movie.

Jeffrey Madoff: By the way, another one that 1984 came and went. Yeah, yeah. I was 40. It was an important year.

Dan Sullivan: It was an important year.

Jeffrey Madoff: But not for the reasons they said.

Dan Sullivan: That's right. So the thing is that we need something big. Let's just put out a thesis. They said, you know, there's so much confusion in the technology world and there's so much going on. We got to have something that really draws a line in the sand. And this is a new world we're doing. So we're going to take all the ways that human beings have created up until now, and we're going to crush them and say there's a new dawning and there's a new vehicle to create in the future. And it's the thinnest ever, no longer frustrating, fat–

Jeffrey Madoff: Did you have to lug around? Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: You have to have a caddy, you know, you have your Mac caddy. Yeah. So I'm just trying to think, or was it just a bad bet day at Apple? They've done other bad bets. This one just attracted a lot of attention. I think there's something going on in the technology world that when you sent me that, I said, this is like the 10th piece of information that's talking about big tech, not really understanding where the world's going and a certain sense of confusion.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think for most of our growing up and most of our adult life wasn't taken up with tech somehow being the savior of the economy and all of the dominant force on Wall Street. So people made fortunes and all the things that happened before have happened since. I think one of the problems is that the opinions are amplified through a 24/7 news cycle, through the social media that if you pause during your scrolling on Instagram or look at Facebook, and you're always looking at things about innovations and iPhone and everything, you get more and more of that same stuff. And all of a sudden you think that that's the world, when in fact it isn't. And I think so many people's noses are pressed up against the glass and they can't see, as the saying goes, there's no glass in the woods, but you can't see the forest for the trees because you're just so focused in front of it. So when I say don't think of a pink elephant, first thing you get an image of is a pink elephant in your brain. And I think that the massive sales necessary to keep this engine going, I'm guessing that as iPhone sales have tapered off, that they figured, okay, so AI, what's the best manifestation of AI in a product that we have? Well, I think that we could really build the case for the iPad and a new iPad when the best thing they can say is it's thinner, which wasn't a problem anyhow. You know, what does that do? And it used to be technology was fun. Okay, the fun is gone. And it used to be, it was fun.

So just to give you another example, just a quick example is the initial personal listening device was the Walkman. I met with Akira Morita and his wife. I was shooting the French collections in Paris, and they passed out around 400 Walkmans. So all of a sudden, for the first time, you were seeing trendsetters in the fashion world and celebrities wearing headsets. We hadn't seen that before. You know, so it was this personal listening device. And they had the generic name for it, you know, the Walkman, until Apple came along and out-marketed them. And by that point, Morita had died. But the way that Sony tried to sell the Walkman then was showing you how compact it was and the technology inside. Nobody cares. What Apple did is they showed this kind of animated thing, colorful animated thing of a guy dancing and having fun. And even their more advanced commercials, a few years later, was a guy dancing up the side of the building and it was, they were fun. This is the fun you can have with this product. Well, where's the fun? Fun sells. Where's the fun anymore?

Dan Sullivan: Well, the other thing that's happened is culturally that when the Microsoft of the world and the Apple of the world, this is the late ‘70s and early, and they were the rebels against the establishment. Well, Apple is the center of the establishment now. They're the most highly valued corporation in the world. And they've lost their innocence. I mean, they were the first company to get a $3 trillion valuation. I mean, that's a big, massive company. And all entertainment, creativity, and humor, and everything is at the margins of the culture. They're not in the center of the culture. They're the center of the culture now.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. And when you mentioned they've had some misses before, their most successful ad campaign for the computer, it was John Hodgman represented, he was kind of the avatar for the PC. The actors named the young male who was IBM.

Dan Sullivan: Microsoft or IBM?

Jeffrey Madoff: Hodgman was just PC, which is really Microsoft. That's Microsoft, yeah. And the young guy, kind of cool and casual guy.

Dan Sullivan: The cool guy, yeah. Was it Mac?

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. And the background was just white, seamless. They were just in a limbo space.

Dan Sullivan: That went on for years.

Jeffrey Madoff: It was incredibly successful. But the way that it started off, Apple was making fun of PCs in a different way, it was much more kind of hostile. And they found in their testing that people gain sympathy for the PC. So Apple changed their approach and made it more that PC was being deceptive. When they say, well, our next upgrade is going to do this. And our next upgrade is going to do this. Well, the Apple thing does it right now, you know, and it was, you can trust Apple. And so it was interesting because our first out of the box didn't work. But then that did, and think about what IBM did. They had the Charlie Chaplin character, right? The little tramp. How credible was that with IBM? Not, right? But, you know, when you think about back to Apple, you mentioned the 1984 commercial, the things that they did, which was about this is against Big Brother. This is against the establishment. As you said, they're right in the center of that now. They're now, they're the crusher. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: Exactly. Exactly. Yeah, they not adjusted to their cultural maturity.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. And they're obviously not the underdog anymore. So then they came out with another product. I wanted to mention this too, the Apple Vision Pro. So there was a week or so when it was first launched and I would see people walking around New York with these big goggles on. And I was with my son and I said, this is not gonna make it. This is gonna be the same thing as like 3D.

Dan Sullivan: Well, it's like Google Glasses that came out 15, 20 years ago.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right.

Dan Sullivan: I think any technology that makes you look like a dork. Like the Segway.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, yes.

Dan Sullivan: I was in San Diego and the cop patrol came by and they were all on Segways. And they looked foolish because they had short-sleeved shirts on and they had shirts on and they were on a Segway and they had a helmet on. And I said, that must be penalty patrol or something. These are all the cops who got in trouble. They send them out to embarrass them in public. Really weird, you know, and the segways just look weird. They never had it. You know where they made it in factories that are a mile long. You know, they use segways to get from one area of the factory to another. But you want this back stage. You do not want this technology. First, same thing with goggles. You don't want to see people in public with goggles. They're disassociating from reality. It's like during Covid, a lot of dogs had trouble with people with masks on. Because dogs really pick up on facial features. A lot of dogs just really, really didn't like people walking around with masks. They want the real goods to check out whether this is a good person or a bad person. But I think that the people who would create these technologies are themselves disconnected human beings. Well, that's right. That goes back to the beginning of our story here.

Jeffrey Madoff: In which way?

Dan Sullivan: The people who made the decision to put this out are fairly connected human beings.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, because like in most gigantic corporations, nobody is going to speak truth to power. They're not going to say, you know, this is a hostile message. There was an actor's strike. The center of it was AI. A writer's strike, the center of it was AI. Creative people are having their artwork appropriated, trying to steal their voices and all of that. And then this is what you're featuring that our technology does. It destroys all creativity. This is not a smart idea, but nobody in these meetings ever says that kind of thing. I think about Avatar, when the first Avatar came out in the 3D. For the next three years, because at that time, the highest grossing movie ever, if you wanted to buy a TV, it had 3D. I didn't want the 3D glasses and I didn't want that feature, so I didn't want to have to pay for that feature. I went to two different major retailers and then went online, everybody had 3D, Samsung, LG, Sony, Apple, all of them had 3D. And then to try to promote it, they would give you two pair of the $75 glasses with the purchase. I didn't want it, okay? Now I see these Apple Vision things. Apparently people, and it's not just that I'm older, young people, like I asked my son what he thought, would you wear that? He goes, no. And it gives you a headache after 15 minutes of doing that. And I would ask a more humanity type of question. By the way, $3,500 a pair for those things. That's another thing. The production and projections of that have already been cut in half by Apple. I predicted when it came out that it would fail. People don't want to wear that. And more so than looking like a dork, I think it's also, do we really need to be more isolated from each other than we are already? That you got to wear it walking down the street. I think everything about it. You know, it might be a nice thing at an amusement park or something.

Dan Sullivan: There's a real role for it because it's augmented reality. You know, if you're wearing it on the street, you're actually seeing the street, but it's identifying with information the stores that you're passing.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, they'll try to sell anything with that, like geo location for buying. Stop in now and get 25 percent off your first purchase and all that stuff.

Dan Sullivan: But what I've heard, there's really fast adaptation of it is in skills training, blue collar skills training, where day one, you're a motor mechanic and you have the goggles on. It says, okay, now unscrew this screw and put it here. Do this. Before lunchtime, you take the engine apart. In the afternoon, it shows you how to put the engine back together again. They do that five days in a row. On the sixth day, they can do it without the goggles.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. And as a learning tool, it makes perfect sense.

Dan Sullivan: I think it makes total sense, but it's not front stage.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right. And flight simulators, right? Same thing. They're not games, though. You know, the flight simulators are as close as you can get to real experience.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I've been in one.

Jeffrey Madoff: But when you're walking down the street, when you're isolated from all the people around you, when I absolutely guarantee you that the merchants that you walk by, if they're national or large enough merchants, you will get a promotional message that you can come into the store and get a discount and whatever. It's just more ways to sell you stuff you don't need.

Dan Sullivan: It's the intrusion of commodification into everyday experience.

Jeffrey Madoff: Beautifully put. You're absolutely right. And that just makes me sick.

Dan Sullivan: Well, the thing is, it doesn't work. Well, yeah. You know, I'm just approaching next month, it'll be six years since I've watched any television. You know, and I did that because, first of all, the Internet gives me all the information I want. It was 800 hours a year. For six years now, I'm getting 800 hours back. And I'm mostly reading. I'm mostly, you know, reading books. But I've found better uses of the Internet. There's a lot of archives of great movies now. What's it, 50 years? What's the copyright? Yeah, the IP on movies, 50 years.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's longer than that, but I'm not sure what that is.

Dan Sullivan: There's all this film noir stuff from the 1940s and ‘50s. There's the thing called internet archives now, and they've got hundreds and hundreds. I really like film noir.

Jeffrey Madoff: Me too.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. It's the dark spot in our two souls. We sort of resonate from dark spot to dark spot. Anyway, but just suppose that it's my experience that high tech, the companies that are high tech companies, the advertising of high tech has become more hyperbolic with the decades, starting in the ‘80s. I think ‘80s is where you started, ‘80s, ‘90s, and then we're into the fifth decade, really fifth decade. And it becomes more hyperbolic as you go along because it's competing with so much existing technology.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's true. But I think that one of the major failings is in the Apple iPad commercial, where all the previous commercials that Apple did showed people having fun using a product. They never talked about the technical specs or anything like that. How many humans did you see in that Apple “Crush!” commercial?

Dan Sullivan: None.

Jeffrey Madoff: None. That's right. I think that's significant. I think that's really significant. You know, it was a machine that was crushing all the stuff that creative people use to create new things.

Dan Sullivan: Since time immemorial.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, exactly right. And the other thing is that most of us are knowledgeable enough to know that what's happening on a moment-to-moment, second-to-second, nanosecond-to-nanosecond basis is harvesting data about our behavior. So all of the worst nightmares about these companies, you know, that were the underdog, you know, there is bad, if not worse than the companies that preceded them in terms of that. And I think that's really significant. You aren't seeing people. We all know the data's being harvested. I believe, and I have believed this for a long time, I said to people, YouTube will have commercials. Oh, it's never gonna have commercials. That's what's so great about it. No, it's gonna have commercials, and so is Netflix. They're all gonna have commercials, except for you're paying not to have them. So what did they do? They actually returned to the original model for television, and they have two income streams. Now you're paying to get rid of them. And the businesses are paying you to put it on their platform. And television and online streaming is in total chaos right now. They don't know what's going on anymore.

Dan Sullivan: You know, I think there's a fundamental constraint and that is that the human brain can only focus on one thing at a time. And it has no bandwidth expansion, except that what you're focused on, that's the only thing you can focus on at the time. And you're competing for that one person's, how they're using their attention. It's actually our property that they want to take advantage of. I mean, I wrote a book called Your Attention, Your Property. And it's just that I choose how I want to use my attention.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yeah, and it's like the author we both like so much, Tim Wu. And, you know, how that's become the commodity is our attention. Yeah. I wrote this down because I really like this. This was a British filmmaker, Asif Kapadia, wrote this about the iPad commercial. This is a quote from him: “Like iPads don't know why anyone thought this was a good idea. It is the most honest metaphor for what tech companies do to the arts, to artists, musicians, creators, writers, filmmakers, squeeze them, use them, not pay well, take everything then say it's all created by them.” I think that's brilliant because it's true. You know, it's really interesting because I met these filmmakers at the Tribeca Film Festival this past week. A friend of mine had a film in it, and I met the writer and director couple, and I met the three featured players in it. And it was really interesting because these were people that somehow got their film made. You know, it's an independent film. There is not a false note in it. It's a beautiful story, really well told. And it's a struggle, of course, to get it made.

And I'm not saying it should be easy. I'm not suggesting that. What I am suggesting is that as the scales are tilting and, you know, the studios were trying during the writer's strike and the actor's strike to cast the actors and writers as being greedy as the CEOs of these companies are making so much money. And it's kind of fascinating because these people are the engines of new, the engines of innovation, the engines of the stories that we love to hear. And I think they are undervalued. Nobody said it's a level playing field, but I think it was Iger, although he denied it, but from Disney, who basically said, when what the stars make less, we'll starve them out. When the strike was at full tilt. And I thought, wow, so as you guys are making tens of millions of dollars and there's a tiny, tiny, tiny fraction of actors and performers that are in that realm, I don't think we realize how dependent we are and how many things good come from that. The film noirs that you love, the music we love, all of these things. It's really interesting. And I think what we're seeing maybe is a shift in terms of what we value, and that could be very interesting.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. We had a party at the office just two days ago for one of our Associate Coaches and strategic coaches, put in 30 years, and now he's created a new company at 80 that he wants to devote his attention to full-time. And there was a person who was visiting, he was a client, he was in the workshop, and he was from Minneapolis, and he had 17 pizza stores that he had bought within the last 10 years. He was talking about it, and I said, what's the name of the pizza, you know, the brand of the pizza? And he says, Red Savoy. And I said, that's interesting, Red Savoy. Where'd that name come from? He says, well, it was an old factory and it had a product that was called Red Savoy. And the guy created his first pizza kitchen in the factory and he was looking for a name and he called it Red Savoy. And they have a lot of history attached to it. It's a company that goes back decades, you know, early 1900s. And I said, that's really good. I think that's really good. I think you have something there. It wasn't a manufactured name from market research for putting focus groups or it wasn't based on big data and everything else. It was just that the guy did it. And I said, I think we're entering a period where retro is coming back. And it's actually among young people, you know, the interest in old things, the interest in secondhand things. For example, lawn playing albums now are back with a furry, you know, and the equipment for lawn playing albums and everything like that. Record players. Record players. I knew there was a name to that. You know, there's a part of us that's tired of new.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think it's that, but I think there's something else that goes along with that. And I think that what it is, is we are all have, and this goes back to our most primitive days, pride of ownership. A link in a download is not ownership. And when you have that vinyl album and you've got the cool photograph or drawing on the front and the liner notes on the back, that is something that you possess, that you can hold, that is a physical object, that's really cool. And I think that pride of ownership is also shifting because that allows you to have something, hold something that has a uniqueness to it. And I think that that's a big thing too. That would be interesting to explore also because what is it that makes something attractive to us? And I think you're right that more and more younger people—that's why vinyl, percentage-wise, is still a tiny part of the business, but percentage-wise, it's the highest growth area and has been for the past number of years now, growth in the music industry. And it's a status symbol for an artist, especially one that's starting out, to also put their album on vinyl. It's like, now, what's the other thing we're dealing with? Instead of movies starting off streaming, only available in theaters. So it's, you know, only available in theaters for those first few weeks now. I mean, I remember growing up when Ben-Hur was held over for like eight months, you know, at the Village Theater in Fairlawn, Ohio. But I think that there's something that is not appealing about anonymous products.

Dan Sullivan: Well, here today gone tomorrow products. And I think this is what the big tech companies are running into, is the falling birth rate that is now the majority of developed countries in the world now. They stopped having babies 40 years ago. And they've always depended upon the big booming youth market for new things. And the youth market isn't there anymore. I mean, the millennials are smaller than the baby boomers.

Jeffrey Madoff: What is it? It's the Gen X that's the one after Millennials, who is another big bump in the population.

Dan Sullivan: Well, the Millennials were a big bump after the Generation X. Generation X was right after the Boomers. And then the Millennials came along, but only in America. The United States was the only one where it happened. And part of the reason is that the U.S. isn't a citified country. The majority of Americans don't live in a city, where in Canada, 60% of the population lives in 15 cities. Because you can freeze to death up here. You want to be close to the fire, you know. But all of Europe, with the exception of France and Sweden, have falling population rates. So, you know, the whole basis for high tech was there was always going to be a growing market. Maybe one of the reasons is there isn't a growing market anymore.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And then what do we return to, you know, your reference, and I think it's, I love the way you put it, the commodification of everything.

Dan Sullivan: The commodification of everyday life.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. And the thing about that is when everything is available all the time, nothing is special. And where does that leave you? With, I think, a sense of disillusionment. And how do you make yourself special? And I think that that was a big problem for younger people. Social media started warping people's sense of themselves and how they present artificially. And, you know, what does that do? And now there's clinical evidence of the damage that that's done to teenagers and especially teenage girls.

Dan Sullivan: That's right. That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: There is such a cascading effect that happens.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I think when you sent that article, when you spotted the article and then you saw the video, you know, it's kind of like a tipping point event. Yes. I think so too.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. Yeah. Really, really interesting.

Dan Sullivan: Apple would be the one that you would least suspect of making that kind of mistake because they've always been good with their consumer advertising.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, but you know, they've lost what they had. And that was, they could always, even long after they weren't, they could play on being that underdog and hip and all of that. And that, you know, it's just not the case anymore. It's not credible anymore. And they become like these other companies. They're General Motors.

Dan Sullivan: That's right. That's what I was just thinking. That's exactly right.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Well, do you think we stayed within our boundaries of anything and everything?

Dan Sullivan: Well, we're starting to choose the topics that the boundaries are not visible when we start off speaking, you know. It was a constraint, but we're trying to loosen the constraint. But I think it bears repeating of accumulating evidence that something big and scary is happening in the tech world. Not necessarily to us, but the people who are in the tech world, they're up against some constraints that they had never thought would happen.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, we're seeing that in the layoffs that are going on in the cutback projections in sales and all these things. But, you know, at a certain point, markets hit saturation. So It's bound to happen. It's like the companies that did so well during COVID when people were no longer restrained by that, there were companies hotter than hell like Peloton who just collapsed and got bought for pennies on the dollar as a result. I always look at these kinds of inflection points, not that I am any expert in investment, because I am not, but these are the times to start looking on the horizon for what's happening, what could be that next new thing. And I think you're also going to see a lot more conservative aspects happening in terms of, you know, product. It's an interesting time because there's so much going on. And I think that we're hitting on something with both pride of ownership, tangible products. What are these things telling us when they fail that big at a message like Apple just did? And especially with a message within that, how people are interpreting it, that's not insignificant. So we kind of missed the mark. You missed everything. And you alienated your own consumers. That's a big miss. So it's an interesting time, and I think interesting times create new opportunities.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, oh yeah. We're always gonna be buying stuff, it's just a question of what we're gonna be buying.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, that's right. Well, I think this has been anything and everything. We've tried to cover that for you. So thank you all for listening. It's Jeff Madoff with my friend Dan Sullivan. ‘Till next time. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

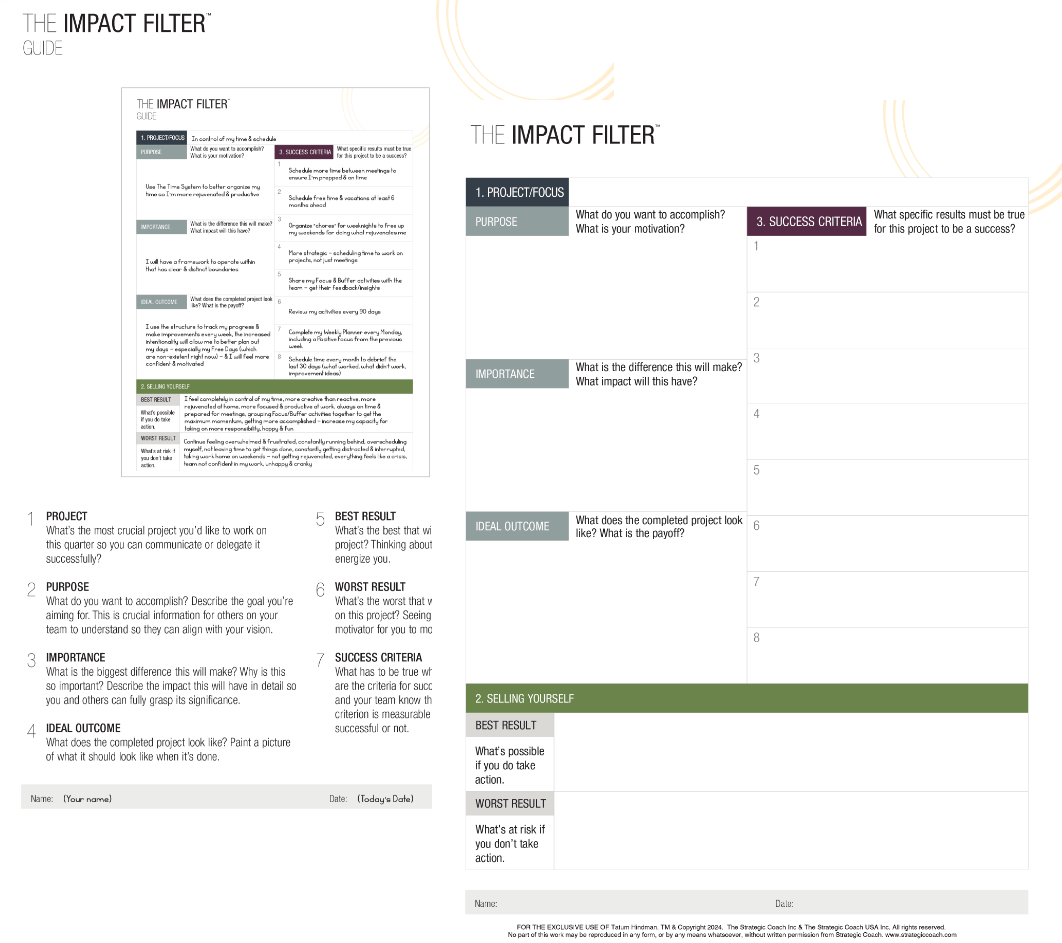

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.