Unpacking The Retirement Myth

September 12, 2024

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff and Dan Sullivan explore the evolving concept of retirement. They discuss its historical origins, the unique challenges entrepreneurs face, and the impact of longevity on financial planning. The conversation offers valuable insights for any entrepreneur hoping to redefine success and navigate the modern economic landscape.

Show Notes:

- The concept of retirement is relatively new, emerging in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

- The word "retire" comes from the French word repérer, meaning to pull back or withdraw, initially used in a military context.

- Otto von Bismarck introduced the first state pension system in Germany in 1889 to address social and economic challenges. By providing financial security for older citizens, he aimed to reduce the risk of social unrest and promote economic stability.

- The United States lacks a mandatory retirement age, making retirement an individual choice.

- Entrepreneurs often resist traditional retirement, viewing it as a withdrawal from their passion and purpose. They see retirement instead as an opportunity for reinvention.

- Retirement should be a strategic choice that aligns with your personal and professional goals.

- As life expectancy rises, retirement planning becomes more complex. Entrepreneurs need to consider extended financial needs and healthcare costs and ensure their ventures and investments can support a longer life.

- Moore's Law highlights how rapidly computing power doubles, reshaping the business landscape. Entrepreneurs must adapt to these technological shifts, which drive efficiency and innovation, to stay relevant.

- The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a catalyst for many entrepreneurs to re-evaluate their career paths and business models and highlighted the importance of adaptability and resilience.

- Retirement is perceived differently across cultures, impacting how entrepreneurs plan for the future. Some cultures emphasize family support, while others focus on individual financial independence.

- Understanding these diverse perspectives can help you tailor your retirement strategies to align with your personal and cultural values.

- Dan’s secret to a long and fulfilling life: Always make your future bigger than your past.

Resources:

Book: The Great Crossover® by Dan Sullivan

Blog: How To Cast A Collaborator, Not Hire An Employee

Personality: The Lloyd Price Musical

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: So you sent me a note, Jeff. What prompted you to have a discussion about the concept of retirement?

Jeffrey Madoff: What was that about? Well, it's interesting. I started thinking about retirement because, you know, you and I have mentioned it a number of times. People say to you, people say to me, are you thinking of retiring? Why haven't you retired yet? Which is never anything that has been appealing to either you or me. On the grand stage, one of the big things that's been going on now politically, and I'm not getting into the gradients or side of the aisle people are on, but that should a sitting president retire, because of whatever the perceptions or realities are about the situation. I'm thinking, wow, so now retirement's taken on, aside from you and I knocking it around a few times, it's taken on this greater significance in our day-to-day life and asking questions because the United States is in a unique place about retirement and how it regards it.

And I got very curious about where did that word even come from? Retire. I thought maybe it was a military word or something, and it was a French word, repérer, and it means back or pull back or to pull out. It comes from medieval Latin, which meant to draw or to pull. So it meant a physical movement of some form. It had nothing to do with jobs or not jobs. And it did then become used as a military term because the to draw back or to withdraw began to be adopted by the military. But retirement as we know it today didn't come about till the latter part of the 19th and end of the 20th century.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, Germany was the first, actually. Bismarck. And they had a problem, and that is that what we would call communist revolutions happened across Europe in the 1840s. 1848 was a big note. There were major revolutions. The play, the movie Les Miserables, talks about a type of revolution that happened in Paris in 1834, okay? And that was just a prelude to the 1848, which was Europe-wide. Paris has always been having, you know, riots. Riots are not an unusual thing in Paris. But the big one in Paris was in 1871, after the French had been badly defeated by Bismarck's armies. The Prussian army, that was a real wipeout. They actually captured the king, not the king, the emperor. And this was Emperor Napoleon III, I think, Napoleon III.

But the Germans were really, really worried about this. And Germany doesn't exist as a country until 1871. Before that, it was just all these little principalities, you know, lots of castles and everything, but it wasn't a unified country. And Bismarck is one of the great figures of European history because he actually pulled all this together. It was mainly because of the Prussian army. And there's a great saying about Prussia. Prussia wasn't a state with an army, it was an army with a state. And he, because of the power of the Prussian army, he was able to unify, and not in a militaristic way, but he just said, look, it'll make more sense if all of us are together. And they had some lightning fast wars against the Habsburg Empire, I think against Denmark, which were strong powers. And they defeated him rather handily, so he had a lot going for him.

But he had one big problem. They had to industrialize really, really fast to keep up with the world. Germany was sort of a backward country, mostly agrarian. And Bismarck realized that it was going to be industry that gave you the dominant hand economically and militarily. And they had a problem. They had too many old workers. He said, you know, we're going to have to pay off the older workers because all these revolutions involve teenagers and 20-year-olds, unemployed. And he says nothing causes a revolution like unemployed teenagers and 20-year-olds. So he created the thing called retirement, where you would be paid not to work. You know, you could stop working and we would pay you not your full salary, but we would pay you part of his salary. And then everybody starting at that point had to contribute from their earliest years into a fund that would then do it. So it's not a very old concept as we understand it today. It's 150 years old.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right, right. I mean, he started the first state pension system and it was in 1889, you know, which was interesting that that is how it started. And the United States doesn't have much in terms of mandatory retirement policy. There are some occupations, commercial pilots, mandatory retirement is 65, and air traffic controllers, again with the airlines, and military personnel, 55 to 65. And in some cases, you know, it's interesting that in the UK, judges have a 70-year-old retirement age, but we don't really have that in the United States. It's largely retirement is like an individual choice. And that has a lot of knock-on effects, which I think is really interesting to Social Security—saving for the future, employee-sponsored retirement plans, which is essentially what Bismarck did, you know, with the pension plans. I can't remember when it came about, but the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, which is fairly recent, but I don't remember exactly when it was, prohibits age-based discrimination, although we know it happens, for anybody over 40. And I think longevity has come to play in this also. Economic necessity has come to play in it, which I think is really interesting.

Dan Sullivan: Well, the entire financial services industry …

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, that's right.

Dan Sullivan: … is based on this concept.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. And in some countries like Japan, and there are several European nations, it's a problem because they cut back on population growth. You know, so how does this get financed? You always need that population coming up and paying into the social security coffers or in these other countries, whatever their version of that is. So I think it's really interesting. And so I'd like us to talk about the modern concept of retirement and how did that evolve and what is the impact on the economy? And then we'll get into talking about how entrepreneurs look at, because they look at it distinctly differently, which is kind of interesting too. So you started to talk about the Industrial Revolution.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think it's a product of the Industrial Revolution, but it's not a product of post-Industrial Revolution, okay. And in the 1990s, I wrote a book called The Great Crossover. It was actually my first book. It's fairly up to date, and what I was predicting is that I read a whole series of articles from the technological writer of The New York Times in the early ‘70s. What got my attention is that the term microchip was just being introduced, because up until then, when Gordon Moore, who is famous for Moore's Law, which is that it seems that this thing which they called that in Gordon Moore's time, 1965 integrated circuit, it was the early attempt, electronically, to create greater speed of processing. Computation, basically, it's a computation. He was noticing, and it's just based on three data points, but about every 18 months, two years, they were processing twice as much information data. They were processing data. And in 18 months, the first time, from one data point to the other, in 18 months, it doubled. But the cost of the computing halved. So they were getting four times return, double the speed, half the price.

And then he noticed a third data point that did the same thing next to 18 months. And he wrote an article which didn't really have much attraction when he did. It was just an article. He said, it's an interesting thing I'm noticing. And he worked for a company called Fairchild. And you know the history because you've done a good history of Silicon Valley. And he was an important engineer at Fairchild. And he said, it's just an interesting thing I've noticed. I wonder how this will keep going. And that's all he did. He asked a question. He didn't say this is going to keep happening. He just said, I wonder if it's going to keep happening. But a lot of people, and this is about four or five years later, they said, well, this is a law. I know he was interviewed, he's dead now, but he was interviewed very late in life and he says, is this a law, a Moore's law? And he said, no, he said, not really. He says, but it was a brand new industry and they didn't have any predictive tools. And somebody grabbed this and said, well, this is the rule that every 18 months, two years, whatever it is, this is going to continue happening.

And the truth is there's a fairly straight line projection since Moore did it in 60 years ago. And he says, no, he says, not a law, but he says, just an interesting thought frame. It's just an interesting structure. And he said, it's more about human aspiration that you can actually project a goal that we're going to get. We're going to increase the speed in the next 18 months and we're going to cut the cost of it, you know, and it's still, right now, it's about 85% true, you know, it varies. But it became the dominant predictive tool in the high technology world.

I was very interested in this because the writer in The New York Times, and they now had a name for it, these things where they were packing more and more power into smaller and smaller things, they called it the microchip. And he said, you know, this microchip thing is really interesting. And he said, two things I can see happening. One is that very large bureaucratic organizations are probably going to have a hard time with this, because it's introducing a rate of change into bureaucracies, that bureaucracies are actually geared to stop from happening—that the whole point of a bureaucracy after a certain point is to prevent any change. Because it's destructive. But he said it's an interesting invention because it seems to be an invention that can be applied to a large number of other inventions and speed up the efficiency of a large number of other things, computers being the obvious one. But he said the other thing is that it can be applied to itself. So chips are used to create faster chips. And he said it seems to be, it has a self-augmentation. That was the term they used, self-augmentation. That the power of today's microchips will be used to create even more powerful, and it goes on and on and on.

I wrote a book called The Great Crossover, and I said, I think what's going to happen is that there's new organizational forms coming out of this in the business world, where it's not about the pyramids that had been created for the bureaucratic world, the big bureaucratic world. And when you and I were born, the world was run by big pyramidical organizations. Government was a big pyramid. Corporations were big pyramids. And then the other organizations, the factories were big pyramids.

In 1960s, General Motors was the largest corporation in the world. They had about a half million workers, and there were 21 levels of management from top to bottom. And lifetime employment, when you and I were growing up in the ‘50s and ‘60s, lifetime employment was a reality. That if you joined General Motors when you were 18, you had a pretty clear path to 65. And Social Security had come in in 1936 under Roosevelt. But it was a bit of a Ponzi scheme because the age was established at 65, but the life expectancy when I was born, when you were born in the 1940s, life expectancy was around 50. Okay, so we're taking a lot of money in, and we're not going to have to pay it off. As a matter of fact, I got interested in this, and in 1996, it was the 60th anniversary of Social Security in the United States, and the average payout for the entirety of those 60 years was 29 months. Namely, people died 29 months after retiring at 65. And that ain't true anymore.

Jeffrey Madoff: Just to live up to our name of anything and everything, when you're talking about Gordon Moore, just for those people that don't know, he and Robert Noyce, who actually worked for Shockley Semiconductor, they were part of a group called the Traitorous Eight, because they left Shockley, who was a psycho, he was totally out of his nut, and Moore and Noyce started Intel. And it's fascinating about that because initially the name of the company, Intel, was more noise. Noyce's daughter said, Dad, that sounds like more noise. Which is true. And Intel, which people think means intelligence inside because it was, you know, Intel inside, was actually the integrated circuitry. So it's really interesting. I won't go any further down the rabbit hole of the computers, but what started with Shockley in Silicon Valley, which is basically apricot and almond farms, changed tremendously to what it is now.

But there were a lot of things after the Social Security Act happened. After World War II, pension funds started popping up all over the place. And wealth management started popping up all over the place. And then in the ‘60s and ‘70s, the concept of early retirement started happening. And I remember a dear friend of mine was going to get a master's in leisure studies. Do you remember that one? Because there was going to be, the computer was going to eliminate paper, it was gonna be the paperless office, and because they were so fast, there would be so much extra time that they needed people who could set up programs for all this leisure we were going to have. Neither of which happened. The offices are not paperless, and people are working more than they've ever worked before. But that was the thought then.

And then in the 1980s, when we started realizing, as you were alluding to, that there's increased longevity, for whatever reasons, and I'm sure there were many, many people, didn't want to retire. And they got into what was called encore careers, doing something, you know, their third act, so to speak, you know, doing that sort of a thing. And so there was a big economic impact that came along with retirement also, which I think is really Interesting, might be interesting to touch on a couple of those because you talked a little bit about just the labor market alone and what that did and longevity and savings and investment. I mean, all those were relatively new.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's very interesting. I have a couple stories about that. I haven't really stayed in touch personally with the, I think there were 56 18-year-olds that I graduated high school from. In 1962, I graduated. And I haven't really gone back for reunions for the most part, but I remember the 25th, I went back, and that would have been 25 and 62. So it would have been 1987. The company existed. We had four or five employees. And I told them, you know, I'm going back. And Babs went with me. It was the only time that Babs ever revisited my past or visited my past. So I came back. I spent, you know, a Saturday and part of a Sunday with them. And I came back and they said, well, how was it? And I said, well, nobody came. They send a bunch of old people in their place. They were 43 and they were talking about retirement, how long they had about retirement. Okay. And not many entrepreneurs in my class, they all had gotten jobs, but they were talking about, you know, and Jeff, if you've ever noticed that when people start talking about retirement, they start aging more quickly.

Jeffrey Madoff: Seems that way, yes.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. So another personal story about a month ago, I went back for a family reunion, and I have a sister 89, a brother 87, a brother 86, and then two brothers 70 and 72, and they're all retired. They're all retired. And to my knowledge, none of them knows exactly what I've been up to over the last 30 or 40 years. But they're intensely interested in why I'm still doing the thing that they've never asked anything about.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you know, so that's a great segue into entrepreneurs. And do they retire at the same rate as the general population? And the answer is no, they don't. And so they have very different reasons for retiring and very different approach to it. They often retire later than traditional employees and many and here's two on this broadcast, continue to work long after retirement age. So how do you see, since you've got clients that have been with you over 30 years, how do you see retirement factoring in? Can you assign rough percentages to how many you see or how do they even approach or talk about retirement or are there those that just keep going and that's not even a topic of discussion?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I've got two or three who are in Strategic Coach and Strategic Coach is a pretty good framework to be looking at because I have a lot of clients. I have 50 who have been in the Program more than 30 years. Now, I don't coach all of them, but I do know quite a number of them. And my longest continuous entrepreneur that I've seen continuously every quarter, we operate on a quarterly basis, he'll be 37 years in the Program. I've seen him every quarter. And what's really interesting is that he's a retirement specialist. He's a financial advisor. We talk a lot about it. We're friends in the sense that we know each other, but we really don't socialize at all. I see him, you know, once or twice a quarter now because I do virtual workshops and he's taken advantage of those. He looks great. He's 73, 74. He looks great and no plans whatsoever. He runs marathons at 73.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, good for him.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, he's in good shape, but he's alert, he's curious, he's responsive, he's resourceful, and he's creating new things in his business. But essentially all his clients are people who haven't followed his example. A lot of them are entrepreneurs, but I would say just to pull a number out, I would say that most of my clients go at least 10 years beyond 65.

Jeffrey Madoff: And do some of those not retire, but actually continue to start up new businesses?

Dan Sullivan: I'm going to answer this in a roundabout way. I introduced a thinking tool about 25 years ago. It was called The Retirement Trick. And I said, my perception of why entrepreneurs retire is for two reasons. They hate the activity they're doing. They don't like doing the activity anymore. It bores them. And the other thing is they don't like the people that they're doing their activity with. And I said, so if you could eliminate the activities you don't like doing and eliminate the people you don't like, what's left over? And they all had a series of activities that they really loved doing. And they had a type of person, a type of customer, a type of client, a type of team member that they really liked working with. And I said, well, why don't you eliminate everything you don't like and just stick with what you do like? And it gave them a burst of energy. And I said, well, how long could you do just being very choosy about the activity you're doing and the people? How long could that keep going? They said there'd be no end to it. I'll ask you that question. If you measure yourself now, you're 76?

Jeffrey Madoff: Five. 75.

Dan Sullivan: If you go back to, let's say, 60, are there people that you just don't deal with that kind of person anymore, an activity you just don't do that activity? And you've gotten very, very focused on who you do like dealing with. And as far as I can see that the present new business that you've created is the most stimulating and exciting of your entire life.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's interesting because I think a real shift happened during lockdown with COVID, you know, because I ended up closing my office. There was no production business happening. There was a tremendous overhead with nothing coming in, in terms of that, because there was just no production going on. And I had to think about what do I want to be doing? You know, and Ralph Lauren had been a client for 38 years. And the interesting thing is, is even though I was dealing with these large global companies, Victoria's Secret had been a client for 26 years, it was like I was dealing with a handful of selected people. But what I realized is that “If not now, when?” became my mantra. And I made the decision to go all in on the play, even though I'd been working on the play while I still had my production company going on. And a production company I can reactivate for the right reasons if I want to.

But what I really wanted to do is tell stories that I wanted to tell, involve myself in projects that I wanted to do, not carry the responsibility of the overhead and all of that kind of thing, which gave me more flexibility. And I had zero stomach for trying to solicit business, you know, and I was very fortunate because I rarely had to over the 45 years I ran my company, almost never had to solicit business, which was very good. But everything I was doing was in service, almost everything I was doing was in service of selling something. The jobs that I then started enjoying more were ones that were radically different than that. Whether I was working with the Harvard School for Public Health or working with Weill Cornell Medical in Qatar. And the through line there is it's always about novel experiences and meeting people I would otherwise never meet. and the creative and intellectual challenge of that.

But when I was then making those choices of, well, do I really want to build my production business back up? You hit it on the head is, and you've been along on this ride pretty much since the beginning, that Personality, the play, engaged me in ways that were more gratifying than anything I had done before. And not that my work wasn't gratifying before, I enjoyed it and all that, but this was all personal. This is all my vision for the stories I wanted to tell with the people and teams that I put together. And that became the answer to, if not now, when? Well, it's now.

And so I think retirement age is, to me, just another artificial benchmark. I don't think that it means a lot unless it's mandatory retirement, which, as we already discussed, is very few things. And to me, what was important is, and what's always been important, is being fully engaged in what I'm doing, enjoying the people that I work with. I still work all the time with the people that work for me. So I have editing and projects that we do. But your phrase, which I love, which is make your future bigger than your past, that's what I've done with the play. And you are correct. It is the most gratifying thing I've done because it's a business, but it's a business based on telling a story that I believe is important and worth telling and putting together a team of extraordinarily talented people to do it. And it's been really great. Retirement though was never a temptation, but I wanted to change what I was doing.

Dan Sullivan: I've never really given it much thought, you know, it's like, would I retire? It's not that I made some sort of profound decision, you know, I'm not going to retire. It's just that everything that I was working on had a future that was bigger than the past. You know, that just really struck me that you can luck into that, or the choice that you make is always make what comes next more interesting than what you were doing before. And I think that from an observer's standpoint in relationship to you, this project just keeps getting more interesting.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you're right. I mean, it does.

Dan Sullivan: And you're meeting all sorts of new people. I mean, we just got a really great update on where the play is. You send it through to everybody who's invested in Personality. West End of London for a play is really a big deal. I mean, this isn't Topeka that we're talking about here. You know, nothing wrong with Topeka, but it's not a theater center. But it really struck me. And then you're meeting all sorts of new people, the two management teams, you know, to get you a theater in London and to have a production in a theater. That's one company. The other one is a casting company. You know, which is crucial for moving your story across the ocean to another country.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. It's a storytelling culture, yeah. What's the guy's name? Shakespeare. I think he wrote a few things. Yeah, good stories.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's very, very interesting. But one thing is that you have to talk about percentages here, that in 1974, when I started my coaching company, Coaching Entrepreneurs, I was just checking, well, how big's the market for this? And just using some straightforward data, one of them being, who does the tax department consider to be an entrepreneur? And it's about 5% of taxpayers would come under self-employed or something along those lines. It was 5% in 1975, and last year it was 5%.

Jeffrey Madoff: Isn't that interesting? Because I would have thought it would have grown substantially. It hasn't. I didn't know it was only 5%. I thought it was greater than that.

Dan Sullivan: So people say, well, what's stopping more people from being entrepreneurs? I said, probably there's no need for them. I mean, the ones who tried to be entrepreneurs and they're not entrepreneurs, there was no need for them. Okay. But I think the ways in which you can be an entrepreneur has expanded enormously from 1975.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, I think that there were things when I started my business, the mere fact that I was a very early adopter of having an answering machine, then I ended up building my first computer. But there were things that I could do and get started where I could keep overhead low. That in itself, now, those capabilities have expanded tremendously. It's interesting because you're right, I love meeting new people. I love the new creative and intellectual challenges. I love the ongoing collaboration with the creative team that I have, that we're going to be seeing new potential cast members remotely first. But it's interesting, the idea of, I've never made a profound decision, I'm not retiring. That was just never anything I even considered.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I mean, we're both healthy and I think that makes a big difference.

Jeffrey Madoff: Huge, huge difference, yes.

Dan Sullivan: And both of us from early always knew how to make money.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes, that's right, that's right. You know, I think that one of the reasons that the number of entrepreneurs hasn't grown, and it's kind of interesting, there are certain stats that kind of say, stay the same.

Dan Sullivan: Well, they have grown because the population is much bigger. So 5% and 50 years later is quite a bigger number of people.

Jeffrey Madoff: Correct, but it's still 5% of the whole because all those things have grown too, you know, so it's still a small percentage. But I also think in terms of entrepreneurship, a lot of people have delusional attitudes or ideas of what it means to be an entrepreneur. And so they think that, oh, I can manage my own time and do all these things. And every entrepreneur I know works harder than somebody who has a job, you know, a normal job.

Dan Sullivan: Not necessarily longer, but harder.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, that's right. That's right. So I think that the attrition rate happens because most startups fail. So there's that attrition rate. And, you know, I think that COVID was an accelerant because a lot of people had to think of other ways to make money. And so I think that there was an accelerant for a while. But you and I were talking earlier before we started recording about lifespan, longevity. And longevity on one hand, if longevity is increased, which it has, and the time that you are healthy and viable as an individual has increased, there are goods and services catering to that market. But it also puts more pressure on healthcare systems, puts more pressure on one's financial acumen and how to manage the money going forward, businesses that are contributing to pensions and all of that. So, you know, it's kind of interesting strains on social security, all of that sort of thing. So I think that longevity—and there's talk about raising the retirement age.

Dan Sullivan: Well, the current revolution in France is precisely because they raised the—one of the reasons there's nothing is ever the result of one cause. But one of them was that Macron, who's been the president in France, he raised the retirement age from 63 to 65. And the country went crazy when he did that. His popularity just, the thing, then, you know, there's all sorts of other factors involved. But that was one that people could really focus their attention on, you know. And nobody in the current political situation in the United States has even hinted that they would even talk about that.

Jeffrey Madoff: There's been talk about changing the age from 65 to 67 for those who were born after 1960. And it's interesting when you see in politics, I remember Strom Thurmond was still serving. He died when he was 100 and he was still a senator and probably didn't know where he was for the previous 15 years, but he kept getting, you know, re-elected.

Dan Sullivan: But he had a habit of getting on a train and going to watch it. He had strong habits, you know, like that's correct.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's correct. You know, so you see that. And of course, in the vast majority of cases, incumbency usually wins out in elections. Not always, but the vast majority of the time. And then we just saw more recently, you know, with Dianne Feinstein. 90. Yeah, and there are people that are very vital and there are those that, whether it's genetics or whatever it is, that their viability may end in their sixties.

Dan Sullivan: The other thing about longevity, it's not like everybody's living into their eighties or nineties, but a greater percentage of people are living longer than they used to live. One of them was just infant mortality. That was counted in the longevity numbers. If you died at one, that affected the numbers if you were one year old and you died. And a lot of it is just, you know, pretty basic. Sanitation was a huge thing. A lot of disease was, you know, a function of bad sanitation, you know, and that has improved in the developed world enormously over the last 50 years, 60 years, and everything like that. But we know scientifically that we don't get to go much more than 120, okay, and there's actually a thing called the Hayflick barrier, and that's the number of times that the cells in your body reproduce, and there's a limit. It's 50 times. They don't have any evidence that cells go too much beyond 50 times. The cells start dying off, and they don't do it this uniformly. Cells in one part of your body stop growing and reproducing at a different time.

And we have a name for that when people start declining. We call it aging. But there's only one record where we actually have legitimate records of a person living to 120, 121, 122. And it was a woman in France who died six, seven years ago. She got to 122. It's very interesting, we were on a conference on longevity and there was a neurologist from Israel who has done the longest deep study of people who have lived over a hundred years old. I think he's gotten, it's about a thousand people that he started interviewing them and measuring them beyond a hundred. So one of the people in the audience says, well, is there any common factor? And he says, as far as I can tell, alcohol every day is the only thing. He said, you're asking me a question, what'd they have all in common? He says, the only thing we could find was once a day they had alcohol. He said, but that doesn't mean that persistent alcohol use is gonna allow you to live longer. It's just, this happened to be the one that they did. But they have nice numbers now. They have some large populations that they can start measuring. Another factor, he says, there are people who never worried about how old they were. That has a lot to do with it. It's just, do you think you're old because of a certain age?

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yeah, I think your own sense of identity. I mean, I also think, by the way, that's what keeps some of us continuing to work. We love what we do, but it's also who we are. And where some people look forward to retirement, you know, to me, what I'm doing is gratifying and fulfilling, and I can't think of something that I would rather be doing instead. And again, we go back to the word, and it means to withdraw or pull back. And that's not an appealing thing because militarily, which is now the most common usage of pulling back, now that stupid term stand down, whatever the hell that actually, I don't even know what the posture is on that, stand down. But when we get into the question of longevity, there's financial repercussions. And there's also repercussions oftentimes within families, if it's an elderly parent that needs care, the costs of all of that and so on. And their retirement pensions and monies and health care don't necessarily cover that stuff. So, you know, there's pluses and minuses.

And where I'm going with this is what we were discussing before we started recording. Older people in the workplace and assuming that you are of reasonable and stable health, older people in the workplace, on one hand, you could say that leads to less innovation. On the other hand, you have more people who know how things work. Let's talk a little bit about that, because you were talking about that before we started recording.

Dan Sullivan: I'll take it back to COVID, that COVID is a great historical event. You know, I remember growing up in the ‘50s and ‘60s, and people talked about the Great Depression, you know, the period of the ‘30s. That was a very formative experience for a lot of people who were then in their thirties, forties, in the 1940s and 1950s. And, you know, having a good job really became important to them. The thing that I find interesting about this is that if you want to use the word job, I've always had good jobs. The main reason is I created them. Yeah, for 50 years at least. I mean, the last time where I had an employer was 1974. We're writing a book right now called Casting Not Hiring, and I think the title of our book really applies to what we're doing, and that is that entrepreneurs cast themselves in a role that they can keep expanding that role. Their role is not a job. They're not accountable to a boss. So what other people are doing at particular ages is of no interest to them because they actually don't have a job, they have a role, and the role is related to the people that they're working with right now on their next best project or their next biggest thing. So it's not a job by any definition that other people would consider to be jobs.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and what's cool to me about our book is we're exploring new ideas. We're looking at things differently.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I think we're defining a differentiation in the whole subject of work that nobody's ever gone this deep with it, the book that we're doing right now.

Jeffrey Madoff: And so when you think about at our age… We'll have to remind each other. Well, the thing that's so cool about it to me is when we started to talk about it and then that sparked your interest and wanting to do the book and, you know, the whole idea of exploring that whole new modality about how you look at hiring and so on. To me, I can't imagine doing anything other than staying curious and wanting to discover other things and thinking about things differently. And it's a good example. Most people certainly don't do well financially off of books, but we might, who knows. But the point of it is, is that exploration and that process. And I think that's another important thing is, if you enjoy the process of what you do, and there are times that doing that process is difficult. But if you enjoy the process of what you do, why stop doing it? And I think that retirement, that pulling back, that pulling out isn't appealing. You know, I don't golf, I don't play cards. None of those things are interesting to me. What's interesting to me and lights me up is new ideas to explore.

Dan Sullivan: And new activities and new results, new goals that come out of the ideas.

Jeffrey Madoff: Exactly. So what do you think are some of the misconceptions about retirement?

Dan Sullivan: Well, first of all, you have to accept that you and I are exceptions to a rule. I'll accept and embrace that. So I don't have any argument of what's the rule for other people. It's just that I'm an exception to it. And not just about this rule. And I'm a great believer in rules. You have to have rules for people who aren't going to think about it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, but I'm sure that you've given thought, and not just recently, but 30 or 40 years ago, that at a certain point, I'm going to need some capital.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah. Yeah. I passed that point probably about 10 years ago that I could easily get to 100 with the capital that I have. Our lifestyle costs haven't increased. Babs and I, she's 73, I'm 80, and what we enjoy in life that you have to pay for lifestyle and that it's only affected by inflation you know, I mean it doesn't go up except for inflationary reasons because we more or less follow the same pattern from one year to the other. There's certain places we like going to, there's certain activities we like doing and that's part of our budget and we could do that right now until we're a hundred and everything's okay okay providing my health's okay and her health is okay.

Jeffrey Madoff: We both agree that we're not suggesting that people shouldn't retire. You know, they should do what they want to do. But you should always, I think, reflect on why you're making the choices you're making and why you want to do it. You know, there are people that look at retirement as the award. Thank goodness we're not in that position. But they look at retirement as the reward for decades of hard work.

Dan Sullivan: Well, decades of not doing what they would really like to do.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yeah. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, I started doing what I really liked to do when I was 30.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. I fortunately even started earlier than that. You know, and there are certain things that I thought I'd like to do that I learned that I didn't want to do. And I think that there are two factors that I always heard adults talking about when I was a kid. These are the only two things that adults seem to agree on. One was how fast time goes. And it seems to me like every week now it starts on Monday and then it goes to Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and somehow it's just going that fast. And the only thing that concerns me about that is I'm having fun. I'm having a good time. I wanna keep doing stuff. The other thing is that my grandmother and then my parents, I would always hear, as long as you have your health. And that's really true, because your options go away. And I think it's incumbent on all of us, you know, because these are choices that you make. Now, sometimes just you're dealt a bad hand genetically, and that's the way things go. But trying to optimize the quality of your life, both emotionally and health-wise, I think is really, really important too. And the weird thing about this age, you know, I've never talked about this part, so I don't know if you're affected at all by this, but our contemporaries are dealing with difficult health issues and some are dying. That's the phase of life we're in, which is just kind of surreal. How'd we get here?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah Well, I'm going to go back and talk about another concept that we developed in Strategic Coach 1990s. We called them The Two Entrepreneurial Decisions. And I said, if you're an entrepreneur, remember that you made two decisions. Okay, and you may not be in touch with the two decisions that you made, and the first decision is you will take total responsibility for your future financial security. You're not passing this responsibility on to anyone else. I'm totally responsible for my future finances. The second one is I do not expect any opportunity until I first created value. I have to do something that's a value to other people before I get an opportunity. And I've based my life on that at least for the last 50 years. Well, that eliminates a lot of other considerations, those two decisions.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Well, and I think creating value, which will then create opportunity, is really essential. When my kids were in elementary school, my daughter didn't like math. So she was opining about the math and she said, I'm not going to use algebra. And why am I learning this? I don't need to do that. And I said, you know, I understand what you're saying, but I think that your credibility greatly increases if you're speaking from a place where you've already accomplished something, and then you're saying you don't want to do it anymore. I said, I know that you can do well in that. And if you do well in that, then you have proven yourself and then you don't have to do it anymore. You don't have to continue down that path. But if all you're going to do is complain about it, that's not credible.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah you know, well, it's really interesting because I just got an email from you yesterday about the future of the play over the next six months. A lot of math in there. Yeah, well, there was a lot of math of why you cut the run short in Chicago. And there's a lot of math involved in creating a showcase in London. And I said, I don't know if algebra is the thing, but I do know I'm pretty good at addition. I'm pretty good at subtraction. I'm pretty good at multiplication. I'm pretty good at division. I find a lot of daily life really depends upon those four skills.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. And so the cool thing was she got the highest grade in her class on the next math test. I said, so now when you talk about it, you're speaking from a position of being credible. As opposed to just sour grapes. And you're right. Both of my kids are very savvy, math-wise, financially, and all of that kind of thing. And that's a life skill. And I think that that's just really essential to know. You know, my kids are living in New York City. It's expensive.

Dan Sullivan: Gotta know your math if you live in New York City.

Jeffrey Madoff: That is correct.

Dan Sullivan: You know, pretty much—actually for future planning, you know. Yeah, I mean, it's really interesting. We've lived in, I've lived personally in Toronto for 53 years. And the main company in our whole business, we're in three countries. U.S. is huge, and Canada and the UK. Somebody said, you know, why do you live in Canada that has such high tax rates? And I said, well, you know, there's a way of looking at that. And I says, for the last 25 years, 80% of our revenues are in U.S. dollars, and 80% of our expenses are in Canadian dollars. And the difference over 25 years has been 26%. We're not getting 26% because it's 80%, but it is 20%. Every dollar that we take in from the United States is worth 20% more in Canada. And, you know, you can be more relaxed about your tax bills when you do that. It's dollars. We were able to build a company just because we had that exchange ratio for 25 years. You can build a really good company and it's only been for a total of 12 months over the last 35 years that the Canadian dollar has ever been even or greater than the American dollar. So this morning it was $1.36. First thing I check when I get up every morning, what's the exchange rate? The reason why you know a lot of math is because you zero in on just the math that's really important for you.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. You know, the interesting thing also is the math and also the ecology of you mentioned how you've got enough money for you and Babs to live to 100 without worrying about anything. But you didn't just start planning your finances within the last 10 or 15 years. That's another thing, whether you retire or you just want, and this is my case, it's not about retirement, it's about having the financial wherewithal where I can afford to say no. I don't want to do that. That's huge to me. As opposed to having to take work. And that's really important. Which takes me to another thing that I would assume you have dealt with with your clients. Retiring, if you stop what you're doing, if you withdraw, whatever, oftentimes one's identity, and I think it's even more true with entrepreneurs.

Dan Sullivan: I think it's even more true with men than women.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yeah, and I'll bet you that changes too over time. But yes, I think you're right. How much does that fear of the unknown and their identity that how they had defined themselves for the previous 30 years or 40 years changes? Do you see that as an issue?

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah. I'm just going to throw in another definition of retirement that I got from the Oxford English Dictionary, and that is to be taken out of use. Technology is retired, you know, it's taken out of use. Horses are taken out of use. I think if your identity for your whole life is being useful and then you're taken out of use, I think your identity just got destroyed.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, which is major. That's trauma at a late stage in your life.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, my father was a farmer, and then the farm failed in 1955. He was 45. And within the next five years, he had recreated himself as a landscaper. So from age 50 until age 82, he had the best part of his life. As a matter of fact, his best business year was the year before he retired at 82, okay, and left my mother really well off and everything like that. And I remember talking to him. And one of the things I noticed one day I went home and I said, Dad, I just like to go around because you go out and you visit all your jobs. I'd like to spend the whole day with you. And we'll go. And I always chatted a lot with my father. So it was an easy day. And I discovered some interesting things about my father's work, that the actual taking care of plants, taking care of lawns, taking care of shrubbery, he used up about 20% of his work hours. The other one was socializing with his clients, and all his clients were women because their husbands had all died. He was the man in a lot of these women's lives.

I'll just recreate the script of what went on in these social events, and we did about eight of them in one day, so I remember it. Mr. Sullivan, oh, Dan, your father is an amazing man. I talk to everybody, all of us women. We talk about Mr. Sullivan, what he can do when he's 80 years old, what he can do. And he's just amazing. I wish my husband had had his health. I wish my husband, and it was just nonstop, this positive feedback. It was all applause. He had 20% of actual work and 80% of applause. For a theater company, that's really great. It's really great. And it was that interaction with his appreciative clients that kept my dad alive.

So he's 82 in December of 1992. He's 82. He says, that's it. I'm not going to do it anymore. Died nine months later of prostate cancer. Okay. He didn't have anything going that would recommend prostate cancer. He had high blood pressure under control. He had high sugar under control. And he had had it for 25 years. He smoked three packs a day until he was 60. And he hadn't smoked at all. So there was nothing about what causes prostate cancer. Well, all men have prostate cancer inside of them, okay, but if you have a future bigger than your past, your body says not yet, not yet. You can't do it yet. You're getting nearer and nearer. I had prostate cancer in 2016 and 70 percent of men have the cancer in their body. But if you don't have a reason to die, it doesn't give any encouragement to the cancer. But the day my father didn't go out and meet with his clients, he didn't know who he was.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. And I think that so much of our identity is derived from what we do. But yeah, so I think it's a really interesting topic, especially, frankly, at our age, it's an interesting topic. And something that was never viewed as desirable by either one of us. And how tied up one's identity is with what they do. I am always willing to be judged by my enemies, by people that I don't like because the important people in my life, what's there is so meaningful.

Dan Sullivan: We're on to next Sunday. Yeah, I got a lot out of it. You know, I would say probably since age 60, it's been a conversation that other people want to have with me. And it's not a conversation that I really want to have because it's meaningless to me. And that is that the next quarter is going to be better than any quarter I've had before. And if you think in terms of not individual effort, but in terms of teamwork, that's very good. My ability to create teamwork at 80 is 10 times better than it was when I was 70. Using other people's skills and giving other people purpose for their skills.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which is a whole, by the way, other thing tied into identity and purpose in terms of …

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Anyway, so far, so good.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I'm happy with this podcast.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that we have stayed within the perimeters of anything and everything. And I think we were getting nearer to both of those concepts. So I'm Jeff Madoff with my friend Dan Sullivan. And don't retire from watching this podcast. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

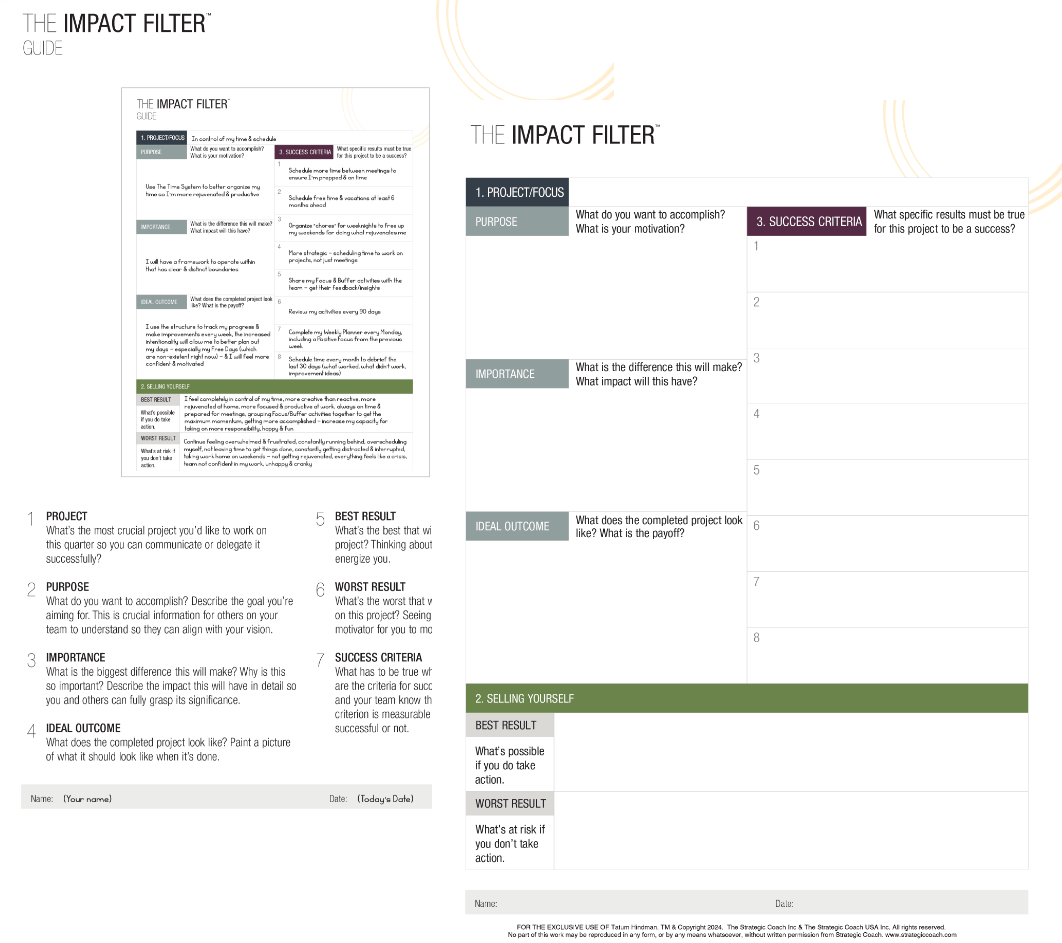

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.