Reimagining Work In The Age Of AI

December 02, 2024

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Will AI be a burden on human creativity, or will it free us up to innovate in ways we never thought possible? Jeffrey Madoff and Dan Sullivan predict how artificial intelligence will reshape work, culture, and the economy. Explore the balance between tech advancements and human connection, and discover the surprising ways AI might redefine fulfillment in our lives.

Show Notes:

- AI is set to transform many job sectors, especially those repetitive tasks that don’t bring joy. This isn’t just a challenge; it’s an opportunity to rethink what fulfilling work means.

- The idea of finding fulfillment in work is a relatively new concept. In the past, we were focused on survival and stability.

- As AI takes over more routine and repetitive tasks, people have the opportunity to move beyond being consumers to become creators. How will this shift culture?

- Financial security affords people the ability to take risks in pursuing their passions.

- What does the world you’re born into owe you? What does the world you’re given allow you to create?

- Will AI be the common “enemy” that brings us together?

- Dan believes in strengthening strengths instead of fixing weaknesses.

- Goldman Sachs estimated generative AI could automate activities equivalent to 300 million full-time jobs globally.

- New technology always creates new jobs, however, and we tend to forget that when we focus only on the disruption.

- Are we hitting a wall with technology commoditizing the parts of our lives that we find meaningful?

- We can’t ignore the ethical challenges of AI, such as intellectual property rights and data privacy. Consider the implications of unauthorized use of personal data or voices.

- Future conversations on AI will include the seven stages of robots and the essence of intelligence.

Resources:

Goldman Sachs 2023 report: Briggs, J., Kodnani, D., Hatzius, J., Pierdomenico, G. (2023). The Potentially Large Effects of Artificial Intelligence on Economic Growth. Goldman Sachs Economic Research.

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff, and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: Jeff, we've been on sort of a technology human standoff theme now for the last two or three podcasts, and you were asking me an interesting question before we came on, the predictions about AI and robots taking over all human activities, or the prediction that it will, and is that going to happen?

Jeffrey Madoff: I don't think so. But it depends on what realm, right? Because there are realms that it has already taken over.

Dan Sullivan: Strangely, one of them is programmers.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's right. That's right. Now what's been interesting in the past is that every time there has been a new technology that basically just threatens life as we know it, so to speak, there's always been a pushback and there's always two sides. One is a new utopia, you know, which is going to remove drudgery from our lives. And the other is this dystopian view that it's going to get smarter than us and basically end life as we know it.

Dan Sullivan: As no need of it. That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which I think is really interesting because there are lots of useless jobs—jobs that people get no fulfillment from, no satisfaction from, they need the income, but they couldn't even really explain the necessity of what it is they do, which I think also creates its own kind of psychological problems, alienation of their work, and so on. So there's kind of two directions I'd like us to go into, and one of them is, is it important to get fulfillment from your work?

Dan Sullivan: Yes.

Jeffrey Madoff: Thank you. Well, that wraps up this part of the podcast.

Dan Sullivan: Well, if you had a choice between having fulfillment from your work or no fulfillment from your work, I personally would go for the fulfillment as long as the pay kept increasing.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I would say that knowing you, that's not a surprising answer. But, you know, I think that there's a lot of blurred lines, you know, some people look at work as kind of the sponsor for the things they wanna do, whatever those things are. Could be that they enjoy hunting, it could be they enjoy painting, it could be they enjoy race car, whatever it is. And so what I wonder about is, where did this notion, and I know it's built into Coach in terms of having Free Days and that sort of thing, where did this notion come from that work should be fulfilling?

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think it was created by people who wanted their work to be fulfilling. No, but I go back, and we both were born in the forties and we grew up during the fifties and, you know, hit college in the sixties. And I can never remember any adult ever saying, as I was growing up before I left home, you know, went off on my own, that you were supposed to enjoy your work. But you had to remember that a lot of the adults had gone through the Great Depression when even having any work was a plus. And then a lot of them had been through the war, where for a lot of them, being in the service was actually the first time that they had had three square meals a day. So we're talking about a big improvement to life overall that happened during our childhood.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, yeah, I mean, I don't remember when I was growing up. I do remember, I can say that looking through the rear-view mirror, I didn't realize it at the time. My parents never sat me down and said, you know, seek fulfillment from your work. I always knew that I would be doing something. But I think, you know, modeling their behavior, they enjoyed what they did. And so there was an enjoyment that came from the work and particularly from the relationships they built as a result of the work. But it's that fulfillment these days and, you know, all of my work is based on that and trying to seek that and so on. But I work my ass off to try to achieve that fulfillment. And it seems like fulfillment has become, perceptually anyhow, like an entitlement. And I think that that's, you know, you talk about things and we hear, I mean, I remember hearing when I was a kid, you know, in terms of the war effort. There were things that we did as a nation together that I think those opportunities for bonding as a nation have all but disappeared.

And I think that there's such focus on the individual and that sort of thing that we don't have a sense of communal responsibility or looking out for each other. There are, of course, exceptions to that. But I think that that's really interesting because so much is focused on the I as opposed to us. And so much division has been sown over the past few decades at this point. And work, though, is kind of the refuge, if you will. But then we had a thing where when COVID happened, the hierarchy of jobs that were important tremendously changed. All of a sudden we were very dependent on what I would think many would consider to be, and it's not, shitty jobs. That's right, shitty menial jobs. Without those people stocking the grocery shelves, without those people willing to deliver stuff, all of that you know, we had to be thankful for them to be doing what they were doing. And they did it, most of them, because they didn't have any choice financially, didn't have any option. But I'm throwing a lot of stuff out there, but how do you look at that? And the idea of the fulfillment, but there's not the kind of shared us situation that can bring people together.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I'll go back to your comment about your parents. My mother was mostly stay at home, but she was a supply teacher at the local school. So she was outside the home. And my father was a farmer to begin with, and then he became a landscaper after that. And I know he really, really did enjoy his work as a landscaper. I think that the farm work was very uncertain. You know, the agriculture, if you have a small farm, there's just so many things that can go wrong. You know, just the market for certain crops and, you know, the price of things and everything else. Plus I wasn't really old enough to really get a sense from that because I had four older siblings and they're the ones who did the field work. I was in the house helping my mother, okay, and I'd go shopping with her and everything like that. And so I didn't have much of an insight.

But once my father became a landscaper, I did work on some of the jobs with him. And he was a real schmoozer. He was a tremendous schmoozer. And he really engaged with people who were paying for the landscaping work. You know, he would talk, and he'd walk them around, and he'd talk them around. So I think my father was a very social creature, and I think he turned his landscaping into a real social activity. And I took a lot from that. Observing him and how he interacted with his customers and clients, I really took a lot from that. But here's our fundamental question. I think as children, we really watch our parents. And there's two things we really watch. Do they get along with each other? And our notion of male-female relationships is a lot established by how the male and female that was central to our lives, how they got along. And I think how they interacted with their work, we got a lot from that. Okay.

And I said to my clients during COVID, I said, you know, COVID is really good because for the first time, they actually know what you do for a living because you're remote and they can see you interacting on the screen. And your parents finally found out what the teachers were teaching you at school. But, you know, we grew up in good times. You and I both grew up in good times. The U.S. was half the world economy after the Second World War, and they could have run three shifts with anything for about the first 15 years, 15, 20 years. Probably, you were born in ‘49, right? ‘40, ‘48, ‘49? That was the golden age. I mean, that economy in the 1950s was a fabulous economy. You know, so and Akron would have been a real energy center when you were growing up. That was a hot time for Akron. But, you know, it just strikes me. You know, I think it's more fundamental. Is your work meaningful? I think is life meaningful? You know, work is just part of life. And do you find that part of life meaningful? And I find everything meaningful. And it's probably why we have this podcast series, because both of us just find everything interesting from one point of view to another, you know. So my sense is, I don't think you can make work meaningful, but I think individuals can make their work meaningful.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I don't think that things are intrinsically meaningful.

Dan Sullivan: No. We assign meaning to things.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And so I think that in assigning that meaning or define, you know, it's interesting. There's so many places I want to go with this. You and I have been fortunate enough that we followed what we were actually, to use a hackneyed phrase, passionate about. And we were fortunate to make a good living doing that. So the idea of fulfillment outside of work was, of course, having great friendships and people that were meaningful to you and that you could share joy and experiences with and that sort of a thing. But there are people that I know who are in the arts who it's not that they wanted to be a waiter or that they wanted to do those part-time jobs, but they hadn't figured out a way yet to make a living doing what they were passionate about. But those who had certain savvy were able to use their work, as I mentioned, like a sponsor. So they could do those things because they were paid well at work and they didn't look to work to define their lives. You know, that was just, as you said, that's just a part of it. We try to make it all meaningful. I think that now it almost seems taken for granted that things should be fulfilling. And I think that it's important. You have to work for fulfillment. It doesn't just happen.

Dan Sullivan: But I think the people who feel, first of all, the should word is the giveaway word. Should is always related to an entitlement attitude, that life should be this way, like you're supposed to be given something. And my feeling is life is just life, and then it's sort of a raw material, and then you work with it to make it good for you, you know. I like, I like making things good for good for me. And, you know, and I hang out with people who have a similar attitude. You know, yeah, I think the problem is that we generally create a population of consumers, not a population of creators.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, that's a really important thing, I believe, because the majority of us don't want to take risks. And as a result, we still don't want, let me phrase it differently. The majority of us don't want to take risks, but we still want to buy nice things. You know, and so you buy nice things, but it all ends up boring because so many jobs are boring. And almost every entrepreneur or artist I've read about said they had to do what they did. I mean, I have to write this play. I had to make films, I had to write, I had to create. You with your tools and what you do. I mean, it's great because you've built in an automatic feedback loop for each, what is initially experimental, tool that you put out there and what you do. And would you say it's accurate to say it characterized what you do as you are compelled to do it? Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I cannot not do it. Right. Jeffrey Madoff: And I think most people don't have that. And because I think, this goes back to what we were talking about actually before we even started recording, is asking the right questions. You know, if you don't ask the right questions of yourself, if you think that successful is making a lot of money, period, I mean, how many people do you know, I suspect a lot, and I know, people who have done extremely well financially who feel totally hollow otherwise. Dan Sullivan: Yeah, I mean, I meet them less and less. And I think part of it is that just to compare two experiences that we've been talking about for, you know, as long as we've had the podcast, but certainly since you invited us to join the financing team for the play. And I considered that just a great opportunity because I really wanted to be part of a play, you know, in some respect. And it wasn't going to be what I was doing with my life doing the play. But I haven't met a single person that you have involved in the play that I had any sense that they weren’t passionate about what they were doing. It seemed to me that you created a vehicle where a lot of passionate people could get together as a team.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think that's true, but I think it's also, you know, you have talked about that sort of thing too, where at a certain level of financial security, that risk can be exciting because our day-to-day life isn't. And I'm not talking about physical risk, but when you calculate everything and your livelihood is built around risk aversion, I think that that's the lens that you look at things through. And I think something like this gives license to play and it doesn't, you know, none of the people who are involved in the play financially aren't involved to the point that they're dependent on that working out.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and I think that, you know, you've spoken about the group of investors as a whole. I think almost all of them are doing it because they want to show they're not looking for a return. And, you know, I mean, we had the money and we're going to spend the money on one thing or we're going to spend money on another thing. But none of it involved, of it failed, it had any impact on the quality of our life, except you know, doing shiva, which fortunately in your culture doesn't last long.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, it does, it lasts a year. But anyway, but I wear dark anyway, so I'm ready.

Dan Sullivan: You're ready for it.

Jeffrey Madoff: I'm ready for any shiva.

Dan Sullivan: Anyway, but I think the big thing is, I was thinking about this because there's some sort of fundamental observation, I think, when you're born, that you have to make, that the world that you were born into wasn't designed with you in mind. No, I mean, I think it's a fundamental philosophical point of view that you arrived here. You have never found the paperwork where you requested to be here.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's correct. This wasn't my idea.

Dan Sullivan: But you arrive and you say, you know, what do I do with this? You know, what do I do with this, this life? You know, what do I do with it? And my sense is, I don't think we're owed anything. You know, in my fundamental, I don't think, you know, I had this conversation with the people I know really well. And we were up at the cottage and we met these people and they were talking about their children going through COVID, about the fact that they couldn't go to school, you know, and, you know, their social activities were severely limited, severely restricted. And they said, they were robbed. This generation was robbed. And I said, robbed? I said, the things that they couldn't do, did they create those things? You know, I said, I brought up, and this really resulted in a loud outburst on the part of the other person. And I said, you know, for a lot of kids, they were deprived of things they felt that they were entitled to. And she said, that's brutal. That's brutal what you're saying. You don't know the suffering they went through. And I said, well, suffering in downtown Toronto compared to someplace in the world where they're lucky if they have food, they're lucky if they have shelter.

I asked Perplexity, the AI program, I said, what are 10 things that children of affluent parents in the Western world receive that could be considered entitlements, depending on the attitude? And it came back and gave me 10 things, you know, your safety and security of good housing, food, abundant food, and everything else. And I said, they didn't create any of this stuff. It was given to them, okay? And I said, they will be robbed if they think they were robbed. But if they said, hey, this is really neat. We get two years doing something different. Let's create some new things while we don't have to go to school and everything like that. I said, it strictly comes up to each individual and what the experience was. You can't say that they had this experience. You don't know what experience they had. And I said, if they didn't let me go to school for two years, I would have loved it. I had the Britannica Encyclopedia. What more did I need?

Jeffrey Madoff: I remember we had the Encyclopedia Britannica, too. Actually, yeah, we had the Encyclopedia Britannica. That was an ongoing competition in the neighborhood when I was a kid, because we had Encyclopedia Britannica, and some of our neighbors had the World Book.

Dan Sullivan: Or they had Collier's, or one of the other ones.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, but those were both bullshit. That's the real deal.

Dan Sullivan: This is the real deal. That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: And they're pretending like a book of the year.

Dan Sullivan: But my sense is, you know, applying this, I'm just using it from children, but I think the attitudes you establish about the world you live in and what you're owed by the world that you live in persists throughout your entire life. I never thought the world owed me anything.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, when you were talking about, you know, life wasn't designed with you in mind, I think so much has to do with how you are welcomed into the world. And what I mean by that is, do you have loving parents? Do you feel safe? Do you feel respected? All of those kinds of things. Now, there are parents that have tremendous problems in their lives. Many things to overcome that of course, you know, as you can say that you aren't entitled to anything. They didn't ask for the kind of brutal situations they're in either. And do we as a society then, and it's not even the right word, let me put it this way. I was going to say owed, but I don't believe people are owed other than that you have to create your own opportunities. But it is rare to find someone who's clear-headed enough that in the face of horrible odds like COVID, an anomaly in terms of an event like that, that are going to say, well, I see this as an opportunity. And of course, it was an opportunity for a number of businesses to do tremendously well from home improvement stuff and home delivery and do it yourself.

Dan Sullivan: Zoom gave enormous reach. We went global the moment we got Zoom. I said to the team, I said, there's no incentive like no alternative. Yeah, I said we've got to turn our entire company around in three months or we're out of business, right? Yeah, because all our business was in-person in physical locations, and we couldn't do any of that. Yeah. I mean, think about two or three people that totally match your attitude towards meaningful work. That's what we're talking about. And pick one that you can think of who just has this sort of, whatever it is, I'll make something good out of it, you know, attitude. I mean, I know you have some. Well, take Sheldon, who's your director on the play. I mean, I'm sure he had a story to tell about the things he didn't have when he was a kid and everything else. And look what he's done with himself.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, look, I think that there are those people who are strivers and survivors. And I think that there are those people that will take a difficult situation and figure out how to navigate it better than most. And I think all that's true. It raises the question to me in that. Do we … I'm not even sure how to phrase it. So I'll phrase it clumsily, which is, you know, do we have, or should we have, and I know that's putting a certain moral imperative on it, look out for others? Or is it only about ourselves? And if the others are in distress, like I think the phrase, you know, the best of us often comes out or at least is displayed during times when everybody's hit by the flood, you know, or everybody's hit by something where you are then dependent on your neighbor. And I'm using that in a very wide sense. But you are dependent on your neighbor because you realize how fragile at times like that, how fragile life is. And so, you know, one of the tropes is, I don't know if it's true, but that common enemy can bring us together. And that common enemy can be climate, it can be a disease, it could be a war, it could be, you know, all kinds of things. But, you know, it's interesting because you know, life is that whole spectrum, right? Yeah. And your job is a part of that spectrum. Yeah. But I think you and I have the similar inclination to try to make the whole thing work for us. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Well, you know, my attitude that I have, I have a great doctor. I think you met him in Nashville, Dr. Hussey. And he's got this notion of optimum health. And he said, you know, all diseases are the result of not having optimum health and he said, so my whole attitude that's a definitional truth. And he says, so everybody's going after the disease, why don't we go after the optimum health? And he's revolutionary in a lot of his techniques and what he's investigated and how he puts things from outside of his framework. I forget what his specialty was, because all doctors you know, more or less start off with a specialty of one kind or another. And he said that what you do is everywhere that the person's healthy already, make them healthier. Because that gives less probability that a disease is going to come along. You measure them for where they're healthy and you keep strengthening where they're already healthy.

And I feel that way about my human environment, that wherever I've got people who are optimistic, they're energetic, I try to make them more optimistic and more energetic. Okay. In other words, I strengthen their strengths, you know, and that's a central philosophy. I don't try to fix weaknesses because it's a lot of work and it doesn't get much result. But where you take somebody who's got a strong ability and you give them maximum encouragement and you give them maximum opportunity to keep going in the direction they're already going, it seems to have a good effect on everybody else. First of all, they don't become a problem, and then they start doing the same thing to other people. If you do it to them, they do the same thing to other people. The people that you've met, and you've met Cathy Davis, who worked on CoachCon, Shannon Waller and Hamish and Margaux, but each of them showed up with an ability that we spotted right off the bat. And we just kept saying, just keep expanding the capability you have. Okay. And then they started doing that to other people.

So it's sort of, you know, I don't like problems. You know, I mean, I like solutions. And, you know, if you're going to spend your time expanding something, are you going to expand the problem? Are you going to try to stop expanding the problem? Or are you going to expand the solution? So, you know, I mean, if you just talk why we've clicked is that when we would converse, we are interested in a lot of things and we just kept pushing. We haven't found the end of the things that we're interested in together.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, because I think we're interested in anything and everything.

Dan Sullivan: Well, it's not a, you know, it's not a facetious title.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, it's not.

Dan Sullivan: And then you see articles and I see articles and you see movies and, you know, and everything like that. You just keep feeding what's working.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I would say that we're free-range humans as opposed to being caged. So that roaming around I think is very productive.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, we're roamers.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's fascinating because I think it bumps into so many areas because there are people that are born into or fall into very difficult circumstances. I mean, what you were saying about the individuals we worked with on the book with, you know, Margaux and Hamish and Shannon, that, you know, you encourage their abilities and they do that with others. I'm not religious at all, but that comes down to the golden rule, do unto others, right? If this makes you happy, if this makes you feel fulfilled, think about treating others like that, because we'll all be better off the more people we have that feel better about their lives, you know, in general. And, you know, how do you do that? And I think we agree on general truths, even if we might disagree on how you do that. And I don't know that we do disagree on how you do that. But the point being, it's really interesting because we're on this planet, we're in this country, we're in this neighborhood, we're a part of a community that there's people that have different kinds of baggage.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but generally speaking, I don't find people's baggage all that interesting.

Jeffrey Madoff: I would question that because I think you do find it interesting, and I know I do, how they overcome that.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. How they transform. I'm intensely interested in how people transform things. Yes. But that starts with an individual decision on their part to do it.

Jeffrey Madoff: But that individual decision may be based on coming into contact with someone like you, who is asking the questions of them that at some point a light goes on. Yeah. they see something they didn't see before. Because I think a lot of people don't even know why they feel trapped. They just feel trapped. And they haven't reflected enough on what their circumstance is to figure out the way out of it, if it's something they wanna get out of. And that their notion of success wasn't clearly defined. I mean, there's a line in the play … because Lloyd's friends, when he's a kid, kind of make fun of him. And the voodoo lady, Monora, says, don't pay them no mind. They don't think about their future. And Lloyd says, why not? Because they don't think they have one. And that's tragic. And it's very true for a lot of people. And it's understandable why they believe they don't.

And it's just, it's interesting because as I've, as I've traveled the world, you know, the funny thing is over, over many decades, just when I put it out of my mind that I was born in the forties, you and I do another podcast and say, well, we're both from the forties. I'm thinking, what's going on here with my age? How did I get this old? How'd this happen? Yeah, it's really interesting because I think I've become much more effective in two things. One is I know that I don't know a lot. But the quest for more knowledge, for more understanding, for clarity is incredibly gratifying. The conversations that you and I have, you know, it's fun and it's enlightening and it's really good. A lot of people aren't fortunate enough to have anybody in their lives that even cares about them, you know, and I think it becomes harder or they succeed in certain things with tremendous chips on their shoulder and anger that accompanies it.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, but you know, if I accompanied you for a month, let's say, on a daily basis, you know, I met you for breakfast, and then we went through the day, and I asked you what your day's about, I don't have any memory of you spending much time with people like that.

Jeffrey Madoff: No, although I'll tell you one thing. No, I have talked to people in that situation. I have tried to learn certain things about them. I'm not saying that to cover all. I mean, that's true, because I remember even when I was a little kid, I would see somebody working on fixing a street and wonder, what's their life like? What do they do, you know? And some of them are laughing and they're having a good time and they're fixing that hole in the street. And so me and a few other kids from the neighborhood would show up every morning just fascinated by this, you know, 20 foot deep hole they dug in the street and to talk about it. And it was kind of interesting. And I think, you know, I was starting to say as I've traveled, the well-worn phrase, but it is true, is people are people. And I have found this to be true all over the world. And that's more, of course, on an individual basis, but people are people. I mean, I feel good that I've been able to make people laugh who don't even speak English. That I have felt a communication with people whose lives were tremendously different than mine, And I think that we all have, there's the basic human needs that we all would be better off if we could accomplish.

Dan Sullivan: Which is mutual respect. Yeah, well the thing that I picked up, and I don't know where I picked it up, I think possibly my mother would have been instrumental here. And she said when, and I don't remember her saying this to me, but I'm thinking about where I would have picked this up, is that everybody's the center of their own universe. In other words, everybody's got a 360 around them. Okay. And a lot of their 360 doesn't really intersect with any of yours. Right. But there is this person at the center, you know, and what everybody wants is respect. Right. I think the big thing, so I always try, regardless of where the person is, to have an attitude toward respect. And I also believe that everybody's life is a full-time job. Oh, that depending on the circumstances that you're born into, that that's a full-time job of whatever it is. And that would go from really poor to really rich. And sometimes I think that being born really rich and being unhappy is a bigger trap than being born poor and really unhappy. Because you're not supposed to be unhappy. You're really rich.

Jeffrey Madoff: My grandmother, who was a very insightful person, used to say, it's better to be rich and healthy than poor and sick. You're right.

Dan Sullivan: I had this lady, she was 70 years older, so I remember when I was 8, she was 78. And I got talking to her because they had a dairy farm, we had a produce farm, so all of our milk came from their farm. And I was the one who went over and got the milk and the cider jugs, like a big cider jug. And I would talk to her, you know, and, you know, I'd ask her all sorts of questions about the farm and when did the farm, you know, when did the farm start. And her grandparents had created the farm in the 1850s. She was born in 1873. And I was just asking her questions, you know, how'd you get work done? You had no tractors, you had no electricity. And she would talk and she would talk and, you know, how you had a lot of help. There were a lot of people who came and worked a season or they, you know, they did odd jobs and everything like that. So there were a lot of human beings interacting. And, you know, when they had harvesting, the farmers helped each other out with bringing in the hay and bringing in the wheat.

And I was always struck by the fact that she had a full life, but she had never once spent a night outside that house. She was 78, and every night of her life she had spent in that house. But she had friends and, you know, it was busy. There was lots of stuff going on and everything like that. And I just got this feeling that nothing she talked about really related to me at all in the way that I was growing up. But it just struck me she had a full life, you know. And up north, we've acquired another property next to us. And there was a run-down cottage there, and we had it torn down. And they had teams of people coming in who were putting in the new foundations. And none of them spoke English, none of them, except they seemed to know fuck. That seemed to be the English word that they seemed to know. I didn't know what language was, but I knew what that word meant. I was just listening, and they were just having a great time. They came in, you know, and they were probably, who knows what kind of money they're … but they were having a great time all day, you know, and I was just sitting there listening. They've got a life, they've got, you know, they've got an income, they've got kids or whatever going on. And, you know, I went home for a family reunion and none of my siblings have done as well as I have. As a matter of fact, none of my siblings actually know what I do for a living and have never asked me in 40 years. Isn't that amazing? I tell you, Jeff, not one question in 40 years. Not one question in 40 years. You know, I flew in on British Airways first class to come to the reunion, and then I got back on British Airways and I flew back to London.

Jeffrey Madoff: I'm picturing the plane at the parking lot where the reunion was held.

Dan Sullivan: I had a few connections before I got there. But I came by limousine, you know, a car picked me up in Cleveland and delivered me there. But they never knew what I wanted to do for a living, but all of them are really keenly interested when I'm going to stop doing what I'm doing.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you don't know what you're doing.

Dan Sullivan: Well, how long are you going to go? Well, how long are you going to keep up at it? And I said, well, yeah, yeah, I like it. You know, it's getting bigger, it's getting better. I don't have any date in mind, you know, when to stop doing it. And I would say with very few exceptions, they could say that about themselves. Now, they grew up in the same household with the same parents, but you can see there's even radical difference at that level.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's fascinating, you know. Yeah. We're unique. Well, you know, I think about, there was this house, we walk home from elementary school, and there was this house on the corner that was pretty overgrown with ivy and so on. And if you walked on the grass, if you just cut a little bit of the corn, you walked on the grass, the woman would come after you from the house and run after you. And then, of course, we were little kids, but we could outrun her. And the strange thing was she wore men's clothing. I was probably, I don't know, nine years old, something like that. And so it used to be a thing because then the kids would yell when she was running after them and then she'd chase them for maybe two houses worth and then go back. And it was great fun. Yeah, but it bothered me.

And I walked by her house and she was, you know, at her garden. And I had to build up the courage to do it, but I walked up the sidewalk to her place and she turns around and looks at me. And she said, what do you want? Get off my property. I said, I just wanted to ask you a question. What? Yeah, I see that you're wearing men's clothing and I know it upsets you, and I've been one of the kids that ran across your lawn, and I was just watching you garden, and I just wondered, well, who are you? Why do you wear men's clothes? What's going on? And she comes over to me, and she says, my husband died, and my life went upside down. I wear his clothes to remember him and I don't want people trampling on those memories and on the lawn that we planted together, on the garden that we tended together. And that's why I wear men's clothes to remember my husband. And that's why I'm so angry when people are trampling on that memory. And then she put her hands on my shoulders and said, thank you for asking me that question.

And I told the kids, actually we were walking home and I said, don't walk on her lawn, leave her alone. And she would see me and wave. And that made such an impression on me because I had no idea of the sadness and the pain that she was experiencing. That would even make her lash out against us kids. I mean, she never caught anybody. She never hit anybody. And us kids teasing her, I saw as no longer, that wasn't fun. That was being insensitive to somebody else's pain and suffering. And that I mean, I'm going back, you know, 68 years or something. I mean, that had a big impact on me because I realized we don't know. In so many cases, we just don't know what put that person over the edge.

And I'll just add one thing to this is when I was, you know, this is probably back in the eighties. I was visiting Akron and I went down to the main post office to pick up this package for my dad. And so I get there and there's this old guy behind the, well, it's almost like a teller's window at the post office. And he asked for my identification. And he said, oh, Madoff, are you Ralph Madoff's son? I said, yes, I am. And he goes, dad's a good man, really good man. I said, oh, thank you. Thank you. I'll tell him you said that. He goes, yeah, I knew him. We were kids together. Good man. I said, oh, thank you. And I left and I thought, that's really an honor. This guy who my dad probably hasn't seen him in 20 years. And you know, my dad was reasonably successful. And this guy was working downstairs in the post office. But he remembered the kind of guy that my dad was. And I thought, that's a wonderful legacy that somebody remembers you with kindness. And, you know, which is really kind of great. And I told my dad about that. And, you know, my dad really didn't know who the guy was, couldn't remember who he was, but it was also like, and I think you and I have talked about this with potential clients having a dinner and people who treat waitstaff badly. And it's like, it doesn't make me think you're important, that you're an asshole, you know. And I know you don't like that either, you know. That's behavior that already gives you, as me, an indication, I don't want to be with this person.

Dan Sullivan: You know, well, it ruins the dinner, too. It does.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, because if you got at least another 45 minutes with that asshole, you'd like to.

Dan Sullivan: Well, the other thing is that the person who's been badly treated will remember that you were part of the scene. I hadn't even thought of that part, but it just dropped in one of our workshops. Somebody was talking about somebody. And I says, you know, people who give you a rough time are having a rough time.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right, absolutely right. And, you know, it goes from you hurt me, I'm going to hurt you back, to I've been hurt and I'm going to hurt you back.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And I think, you know, consciousness of what your life is about and consciousness of who you are has to be worked at.

Jeffrey Madoff: Absolutely.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I mean, I don't think it comes naturally. I don't think it totally comes naturally. I mean, first of all, you have to be committed to being clear about how things are. But one of the things I'm real clear about in the case of my own family is that my siblings did not take advantage of knowing my mother and father, and I really did. You know, I really knew who these people were, you know, and I spent a lot of time talking to them about their childhood and how they grew up and how they did that. And I think that I'm just keenly interested in other people's experience. And I think we share that. I just like hearing other people's stories. I just like, you know, and, you know, and you can ask them questions about what they say and they get new insights if you, you know, put things together. And it seems to me like we're really wealthy in terms of other people's experiences.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I think you're right. I mean, I haven't told that story about that woman who wore her husband's clothing, I don't know, maybe ever. Maybe ever. Yeah. But I felt it like I had experienced it back then and how bad I felt that we made fun of her. And then realizing, instead of feeling bad about it, do something about it, which will get the other kids to stop.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, just going back to the starting theme of anything and everything today, it was about finding your work meaningful. But you just demonstrated how you find anything meaningful.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Find out, you know, what's going on. You know, ask a question. Ask a question.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Yeah, that's right. And, you know, somebody, everybody, needs to feel like they're heard.

Dan Sullivan: You know, Chris Voss was there and that's Chris Voss’s full—you know, you saw Chris at Nashville and he told the story about the terrorist who had kidnapped the American. He trained the, I think it was Filipino, I don't know it was Philippines, which country it was in. But it was, you know, they were dealing with very serious terrorist situations. And he says, I really understand why your position, you know, and he recounted about 10 things from the terrorist life. And he says, so I totally understand why you're doing this. And they let the hostage go. He wanted to blow up the world because the world wasn't listening to him. Right.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. No, you're right. You're right. It's fascinating. And so, you know, what we've been also talking about is all the things that AI is incapable of, which is compassion, caring, desire to learn, the feelings, sense of others, all of those things. And, you know, it's been, you and I've had this kind of ongoing theme, you know, when technology replaces human effort, where there's times that that becomes a good thing, like with cotton gin or whatever. And then there's things that actually, just on a very practical level, you can differentiate your business by having a human being respond to your client as opposed to the endless loop of customer service, which is such a contradiction in terms. Because through the voice prompts, you don't get any customer service. And I think that that's really interesting. Next time, let's go through those seven stages of robot replacement. And, you know, the people who fear AI and the people who embrace it, what are those things so that you can ground your feelings in something in real world examples, which we both have? You know, to do that. It's really fascinating.

Dan Sullivan: Well, I think we're at some sort of wall right now. I'm feeling that we're … I think you mentioned Goldman Sachs? Goldman Sachs and the report that they came out that none of the corporations are making any money on AI. They're pouring an enormous amount of money into it, but they're not getting any money back. And I think we've sort of hit a wall. And the big thing is that the economy only works if you have confident consumers. The only way any economy works is if you have people who are confident about spending their money. It's easier to do that if you have a well-paying job. So if you're threatening people's livelihood with technology, they're not going to spend.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: I mean, if you're using your 401k to buy next quarter's groceries, that's not a confident person.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. And spending is what drives this economy.

Dan Sullivan: Oh yeah. Yeah. This man who I've mentioned several times, Peter Zion, who talks about the world, and he said the Chinese made a guess and a bet that they were only going to have to be this export country for a while until their consumption economy kicked in. Okay. So for example, the U.S. is only involved in exports and imports to 10% of the GDP. 90% of the U.S. is just Americans making stuff and Americans buying it. China doesn't have any consumer population that's confident about the future right now, except at the very extreme high level, and they're trying to get their money out of the country. But if you're in the United States and you're talking about technology replacing the workers in the United States, you're very, very ignorant about how the economy actually works. Go a little deeper into that. Well, if they're not working, they're not consumers.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Yeah. And, you know, we tend to think of technology, new technology, again, as either the utopian outcome or the destruction of the world as we know it outcome, we're always going to wind up somewhere in between there. And this is from Goldman Sachs, which is generative AI could automate activities equivalent to 300 million full-time jobs globally, according to a recent estimate. And many of these are in office roles, like administrators and middle managers, and people that are doing jobs that if they didn't show up, nobody would know the difference. There are so many of these jobs, which I think are being eliminated somewhat by remote work. But also when new technologies came in, for a while, of course, all the blacksmiths went out of business. And the few that were left could charge a lot more for their services because of the scarcity. But there's always, you know, there's always jobs that the new technology creates.

Dan Sullivan: There's always a new thing. Yes. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. I get a lot of this conversation through my connection to Abundance360 and they have this magical formula called universal basic income that in future the economy is going to be so big and it's going to be so abundant that everybody can be paid not to work. And I said, how is that going to happen? I'm just trying to think, how does that actually happen? Since the economy depends upon consumption, if nobody's working, you can't be telling me you're paying people $200,000 a year to be not working. I said, I don't think that's really feasible. And they said, well, maybe we don't need the human beings at all. And I said, you'd notice. Yeah, you know, it's lonely. You know, my sense is that we're hitting some sort of wall because the number of articles that are coming out the restaurant article, and I think it has to do with an extreme arrogance about what technology is. And what is that arrogance? Well, that machine intelligence can surpass human intelligence.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, which I think is also, again … they're not even comparable.

Dan Sullivan: You're not even talking about the … I mean, just take the incident of you going to talk to the woman in men's clothes. Tell me the program that can figure that out the way that you did. Something's off here. Why is she so unhappy? And why is she wearing men's clothes? I think I'll go ask her, you know, and observe something about her. I'd just like to know what's going on here. You tell me the program that can do that.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Exactly.

Dan Sullivan: And on her part, the program that can respond the way that she did.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. And that's why I was saying that our discussion, although we have certainly gone into the anything and everything realm, is also just that that conversation could not be had via AI. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: Well, first of all, the programmers don't have enough humanity in them to actually pull it off. Yeah, I mean, you could write a play, you could do a movie on that incident. In other words, if you filled that scene out and took it into several more dimensions, you got yourself a great movie, you got yourself a great play.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, there's actually a play coming out called McLean, which is about AI and this writer who is using AI and the impact on life. It's going to be at Lincoln Center, I think, and it's Robert Downey Jr. I think it's a two-month run. A friend of mine read the script. He said it's a really interesting story about AI and the impact and ethical questions that raises, which is good. You know, the interesting thing also about AI, why it's used for customer service and telemarketing and those kinds of things, is because AI doesn't care if a customer is rude. You know, they aren't affected by the rudeness. They don't need to have four drinks after work from dealing in that hellscape of an office that they were working in, or having to listen to iRig. And they're not affected by rejection. And I see that because I get so many emails.

Now I get emails, aside from notices on my LinkedIn account, you know, to fill the pipeline, or offering me, you know, your business should be seen. It can be on Inc. and Fast Company. And of course, they don't tell you that, of course, you have to pay for that exposure. I actually wrote back to the person, because I got seven emails or something. So I decided to just write back and say that I'm not in the market for what you're doing, and I don't pay for editorial. And let's see, but it looks like I finally stopped getting stuff from them. I think once you tell them you're not in the market. So I thought, just leave it alone and just keep dumping them in the trash without reading them. I decided that simple word is, I'm not in the market for what you're offering.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, that's like going to English-speaking Canadian films. French-speaking is really good. They have a whole industry in there. They're really good. I mean, they're real movies. The English-speaking is all tax subsidized by the Canadian government. And there's about six people who determine what's a good movie. I remember we went to one and it got great reviews in the paper. We sat down and the opening scene said something Nova Scotia. I said, oh, I'm not the target market for this film. I got up and I walked out. Just that they have such a commoditized theme to them. They're all very introspective. There's a lot of isolation in them. Business is a bad thing in them. America is a bad place. They have the same theme. Yeah, the French-speaking movies are really, some of them are really, really great. You know, there's one, I don't know if he's still even alive, because I saw the movie about 30 years ago. His name is Denys Arcand, and it was called The Fall of the American Empire.

Jeffrey Madoff: Hmm, I don't know that one.

Dan Sullivan: And it's really great. It's a series of three films that were done. He did it when he was in his twenties, when he was in his forties and sixties. I suspect he's not around anymore. But they followed the same characters. And they were university professors in Montreal. And they were Marxists. They were Marxist university professors. And so they have one movie about them in their late twenties. You can be a professor in your late twenties. And then another one in their late forties. And this one was really interesting because they've all died. This one professor has left, and he's got a serious disease, and he's put into a hospital in Montreal, and it's a ward. He doesn't even have his own room. He's got a ward. And the only person he can even reach out to is his son, who is a hedge fund manager in London. And so the son comes home to help him, and it's got great, great humor to it.

So he walks in to the hospital. He says, Dad, what are you doing in a ward? And he says, well, I'm lucky I was in the corridor before last week, and now they've got me in a ward. And he said, oh, no, no, we don't do it this way. So he goes, and he finds there's a whole section of the hospital that's closed off. They don't have the money to keep it going. So he goes and there's some workmen in there. And he says, well, we're with the union here and we're just making sure that they're not cheating on us. You know, that they're not opening up because that would mean they're trying to bypass the union. And he says, right. Yeah, he says, right. But he says, you know, this looks like a nice space right here. If they were to use this for something special, what would that be? And he says, well, you know, I couldn't allow that to happen.

So he says, you know, I just came from London. There's a really good book here. And he says, I think you should look at this book, and maybe you'd change your mind. And it had $1,000 cash in the book. And the guy says, you know, maybe we can do something. Maybe we can do something here. Then he goes to the head of the hospital and he gives her the book and it's $5,000. And she says, yeah, I think we can make an exception here. So his dad's got this beautiful room. It's got great furniture. What happens is that they talk a lot. He and his father talk a lot, and they've been estranged forever. And the son, you know, takes a real interest in his dad. And the father really, really appreciates his son. His son can change the hospital system in Quebec. In a matter of days, he, you know, just get to the right people and make them an offer they can't refuse.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, it's interesting when you talk about, he took the time to get to know his father. And like, I feel like I knew my parents. Everything was open. There's nothing that was off the table that we couldn't talk about. There weren't any, you know, triggers or anything like that, fortunately. And because fundamentally we are who we are in both reaction and in concert with the various emotions and some things that we felt growing up and all of that, when you mention your brothers and sisters who didn't really know your folks, and it seems like they didn't know each other either, certainly didn't know you. And I remember the guy that I was good friends with, his father died. And I said, sir, you going back to California for the funeral? And he goes, no, I know he's dead. And I don't need any more proof. I'm glad he's dead.

Dan Sullivan: Wow. Some bad stuff happened in that household.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, yeah. But I couldn't imagine feeling that way. And it was like, wow, wow, wow. And another friend who drove cross country just recently with his dad. And it's the first time and the most time they ever spent time like that together. And it was apparently revelatory. So I can't understand not having a fundamental curiosity about why am I who I am?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and I knew them as individuals. I mean, it wasn't that I was their son. It's just that they were interesting people. And I asked them all sorts of questions about growing up and everything. And I could see them, quite apart from the fact that it was my father, this kind of a really interesting person, you know. Same thing with my mother. They were just really interesting people, you know. Both were born in 1910, and they had come from really bad families. Both of them came from very negative families, and they were the exception to the rule. They were very good-willed. They were very caring. They were very responsible, and they turned out to be really good human beings. And they moved us 60 miles away from their two families, and in the 1940s, 60 miles was like 1,000 miles. You could have two flat tires and a blown engine and 60 miles round trip. But I never got to know any of their family. They kept us sort of apart. But I consider myself lucky because I just ended up birth order to spend a lot of time with them. And they were both fifth children. I'm a fifth child. Both of them are fifth children. And I think we knew what the routine was, you know. These are the hours for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. When you're 18, get out of here. So it was good. I mean, I have no scars or anything from my childhood. I just thought it was all really good.

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, that's great. I mean, it's great that you feel that way. So to reel us back into where we started. What is your takeaway?

Dan Sullivan: I think the big thing here is that I just created a diagram. One was technology and the other one was humans. And my sense is that we use technology for all sorts of reasons, but it's our game. And you know, some technology is useful for the game and we experiment and some of it's a mistake. But I think right now, in the 2020s, we're hitting a wall now on how far we will allow technology to interfere with our lives and to take away meaning from our lives. We don't want technology taking away meaning. And I'm not saying we as a conscious whole are doing this, but I think people are starting to rebel against technology sort of commoditizing parts of our life that we find very meaningful.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And the really the unwanted intellectual theft, that is what the seeds of AI are growing from.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Did you see the thing with Scarlett Johansson? That was an interesting …

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes. Yeah. Her voice being appropriated.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, first of all, they asked her if they could use her voice and she said no. And then they appropriated her voice. And that was Sam Altman. Sam Altman was the person who approached her. And I says, God, she felt it was creepy. She didn't want to do it because it was creepy. And she said, what are my children going to think when my voice is everywhere? And then to appropriate her voice, I said, this is creepy behavior. This is very, very—besides being theft, I mean, besides it being illegal, it's also unethical and immoral. And creepy. And creepy.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which is my law firm, by the way. Unethical, immoral, and creepy. Yeah, I mean, so many interesting questions come up and one of the big questions, which we'll open up in another one of our podcasts.

Dan Sullivan: I like that seven stages of robots. I'd like to do that one.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, me too. Me too. Because one of the fundamental questions to answering this with any insight at all is you have to define what intelligence is. And so I think that in the world of anything and everything, we can do both of those.

Dan Sullivan: Yep. Yeah, but I'm noticing there's lots of reports of panic really at the higher levels of corporations because they bet, you know, some of them really bet the ranch on this. Remember the movie Metropolis?

Jeffrey Madoff: Yes.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I mean, what they thought about industrialization, you know, that they could use industrialization. You turn human beings into slaves and then gradually the industrialization will eliminate the need for the human beings.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Yeah.

Dan Sullivan: Well, in modern times.

Jeffrey Madoff: Modern times. Yeah. Yeah. I mean, Chaplin going through those gears, you know, is brilliant.

Dan Sullivan: All righty. I'm going to look at the Hoxton Hotel and I'll see where it is and I'll see what neighborhood and see if I have any hangout places in those neighborhoods.

Jeffrey Madoff: Cool. Thank you. Have you, by the way, have you had a chance to see any of The Prisoner?

Dan Sullivan: Not yet. Not yet. I had a full week since I talked to you last week. I couldn't, but I will. I looked it up. I looked it up.

Jeffrey Madoff: So when you realize it was made over 50 years ago, and it's just, but there's, it reminds me there's a, oh God, I'm blanking on the movie's name now, stars Walter Houston. He's an automobile magnate, Dodsworth. Did you ever see that movie?

Dan Sullivan: No, no, apparently it's good.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's unbelievable because it could have been made today. And it is so unlike any other movie of that era, and a self-reflective business person who's achieved this high level of success. And I don't even want to tell you any more about it. There's no cliches in it. It's really, really good. One of my favorite movies, and I found out it's one of Scorsese's favorite movies. It's fantastic. D-O-D-S-W-O-R-T-H. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

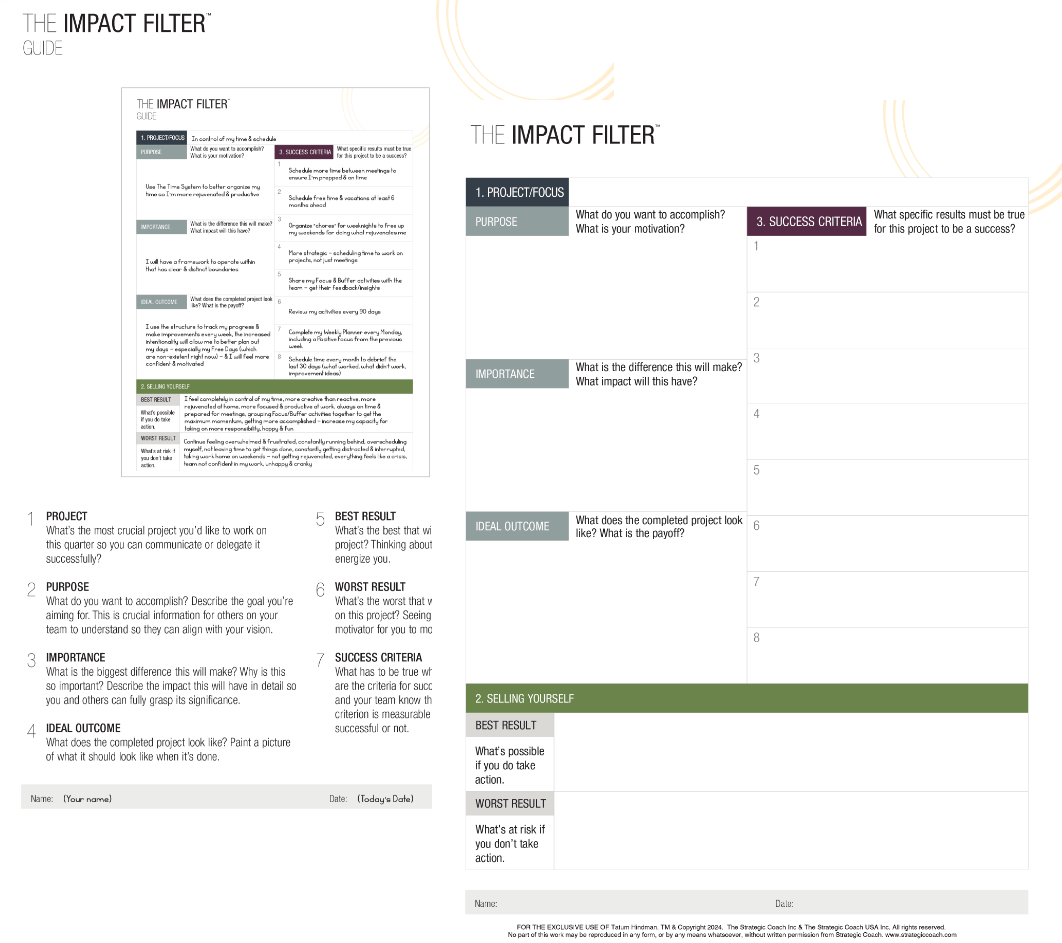

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.