The Evolution Of Technology, From Rocks To Robots

December 17, 2024

Hosted By

Dan Sullivan

Dan Sullivan

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey Madoff

Jeffrey and Dan discuss the intricate relationship between humans and technology as they seek to understand how our thoughts and intentions shape technological advancements. Join them as they explore the historical context of technology, the importance of mindset, and how necessity drives innovation—and discover how our human nature fuels continual improvement.

Show Notes:

- Technology is a human-driven process. As long as there have been humans, there have been humans creating technology.

- The evolution of technology is fundamentally about how humans think and improve upon existing ideas rather than the technology itself.

- Jeffrey and Dan define technology as the intentional arrangement of resources and ideas to create systems that solve problems or enhance capabilities.

- Early technological advancements were rooted in survival needs, such as the management of fire and the creation of tools for protection and sustenance.

- The creation of a new tool will inevitably create inequality because it’s an advantage.

- The phrase “necessity is the mother of invention” highlights how challenges often drive technological advancements, leading to creative solutions.

- Our mindset plays a crucial role in technological development. Those who can envision possibilities often lead innovation.

- Certain technologies become inevitable, and you can either adopt them or resist them.

- If you feel victimized by a technology, that means you see the technology as a force outside of yourself.

- It’s easier to improve on something than to create something new.

- The best learning comes when you put things together in a new way.

- Successful technology development often requires collaboration and the ability to communicate ideas effectively to garner support and resources.

Resources:

The Technological System by Jacques Ellul

Casting Not Hiring by Dan Sullivan and Jeffrey Madoff

Who Not How by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy

Learn more about Jeffrey Madoff

Dan Sullivan and Strategic Coach®

Episode Transcript

Jeffrey Madoff: This is Jeffrey Madoff and welcome to our podcast called Anything and Everything with my partner, Dan Sullivan.

Dan Sullivan: I just started a new book, which I do frequently. Yeah, I finish them too. And it's called Timeless Technology, and the point that I'm making here is that as long as there's been humans, there's been humans doing technology. And I think it's the differentiator between our species and all the other species. And it's basically about how humans improve things right from the beginning. And so it's not so much about what the technology is, but the thinking that goes into technology.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it's interesting because I think first we need to define what technology is in our usual preamble before we start recording.

Dan Sullivan: Let's define first principles.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. How would you define what technology is?

Dan Sullivan: Well, first of all, I think it's intentional that somebody gets an idea, hey, if I, and it's putting together two things. It's having a different use for something that someone sees. And you go right back to the beginning, I use Perplexity. And I said, what are the 10 earliest indications that humans were creating technology? And it gave me you know, in five seconds, he gave me 10 things. And basically it had to do with rocks, shells, sticks, and strangely enough, glue. Glue. And it must have been tree sap or something like that that they used. And they found that if they put two things together and put this tree sap together, it would hold together. And then, obviously, the management of fire was really a huge one. And it had a lot to do with digestion, that eating raw food takes a lot of energy. And they found if they cooked the food, they could get the benefit of the protein without putting the calories in to actually digest it.

And the fire would have been accidental. It would have been lightning strikes or something like that. But pretty well in all the beginning of all you know, early people, that became a big thing that if you got something that was on fire, then you created a management system that when one thing burned out, you would start a new one, you know, and keep the fire going. And they had pots, you know, they created pots and that's where they could carry fire so that when they got to a new place, they could actually do it. And I'm not so much interested in what they created. I'm interested in what was the thinking process that started to evolve, where with certain knowledge and certain skills, we can continually improve things. And I think improvement is the basis of all technology, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I think early technology, my intuition is that it had to do with survival.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, absolutely.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, so we've talked in the past, I've referenced like your fist. And, you know, when there was a fight, you're better off being a distance from your opponent, if you can. And so whoever that first being was, who picked up the rock and threw it, which was kind of a remote fist, if you will, and struck that opponent, that was a very effective way to keep your survival going and to eliminate the survival of your opposition.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and that stone-throwing, rock-throwing would become an immediate skill that you taught to younger members of your yeah, tribe, you know, you had to be good at throwing a rock.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. And so it's interesting when you think about that, because you look at the realm of trajectories and you've got the rocks and you've got a sharpened stick, that's a sphere. So these are all things that could keep your opponent from actually engaging in intimate contact, if you will. And so that's a survival mechanism in order to do that. So then, how do you do that? Instead of one person throwing a rock, you got 20 people lined up and throwing rocks, you know, and they have a little stack of rocks next to them. And what is a cannon other than just a rock thrower? And a slingshot is literally a rock thrower. And that goes back to biblical times, like David and Goliath. So yeah, I think it's really fascinating because the old necessity is the mother of invention. And I think that technology often first started from ways to protect, i.e. survival, to move things forward like a wheel, right? And fire, because it not only could be used as a weapon and to cook things with, it was a sentry, you know, that you would keep the fire going so that those people could see and therefore still be productive into the wee hours. So I think it's really fascinating, you know, where those ideas come from.

Dan Sullivan: I think it's unequal, the humans who can see these things and the humans that can't. So right off the bat, I think the creation of tools created inequality for the people who had a new tool. They could use it to their advantage and not always warfare, but, you know, the gathering of food, you know, eventually over a long period of time, it becomes agriculture. You know, which is really when you think about it is thousands of improvements. We travel to a different part in the city every Saturday and we have a biofeedback program that we have been going through for about a year and a half, Babs and I together. And also we go to a service that's called Osteostron, which are just four machines that you just do it maximum effort, and it strengthens your muscles, and it's only about 10 seconds that you're doing each of the machines. Quite a technology. But when you think about a machine like that and the biofeedback machine we're doing, there's tens of thousands of improvements that had to happen before you have this latest piece of technology.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, you know, when you talk about the mindset. In other words, what kind of mind creates the technology? What were they thinking of? What were they doing? So there's a program that Margaret and I never miss, which is CBS Sunday Morning. It's just great stories. And last week, they had a thing on horseshoe crabs, which I guess if you're another horseshoe crab, you might find one attractive. But other than that, it doesn't translate. They're kind of ugly things, actually. And what they found was that the blood, which is blue, and a horseshoe crab, that if you took that blood from the crab, kind of milking it in a way, it doesn't kill the crab, that that blue liquid, when used with a vaccine, stops any of the toxins from developing in the vaccine. And I'm thinking, who thought of that? Who even thought to look at this?

I mean, all nature's creatures are beautiful. I'm looking at this crab saying, you know, if we take the blood out, as in like a transfusion, and that blue liquid will act as a cytotoxin for any vaccine. So there's a tremendous value in our survival with that. And I'm thinking, how did anybody even think, let's take the blood out of it? They don't even think of blood when you think of a crab. And by the way, a horseshoe crab is neither a crab nor a horseshoe. I don't know what the hell it actually is. Maybe a crustacean, but anyhow, I was marveling at the fact that somebody even thought to try to test that. I don't even know where that idea came from. And that's the stuff that I find fascinating. How did that happen? I don't have the answer to that, by the way, but it's the question of, you know, you see that there's this miraculous result from something to even think about how to test it or even test it in the first place, why would that even occur to anybody?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and we all have examples in our life. And one thing I would, you know, go back to is when you started your apparel company, your fashion company, when you were 22. What were the kind of technical skills that you had to learn when you were doing that? You know, not so much that you had to learn them, but you had to have an understanding of how these things would work if you put a company together that was manufacturing clothes.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, you know, the things that I had to learn, aside from just the various business aspects of it … in my book, that's a technology. Learning the business of something?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, learning the business. First you have to have this, then you have to have this, then you put this together. And you create a system of techniques that actually do that. Back to your opening question. So I said that technology is intentional. And it actually requires a putting together of things into a system. It's a system of action on the part of the human being. It's a system of how do you develop the best kind of things and everything like that. So it's kind of that it's never—a technology is never one thing. It's a whole series of things. There's a how do you use the rock, you know, where do you want the person to be when you throw the rock? What's the best trajectory that gets it where you want to go? And do you have to have a second rock available right away in case you missed? And what happens if they throw a rock, you know? And so my sense is that there's a putting together of things that constitutes the technology.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I think some of that, probably most of it, comes from a discovery of the shortcomings. So, you know, to stay with our rock metaphor, when that rock is hurled and misses its target, you better have another something else quickly behind it.

Dan Sullivan: So you need a pile of rocks. That's right. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Which is not unlike, by the way, going from the single shot pistol or musket and what it took to reload it and then going to the cylinder where you could load six bullets at once. Repeating. Yeah, yeah, you know, which was basically being able to throw six rocks really fast, you know. So yeah, I think that sometimes I don't think it is intentional in the sense that you're looking for a particular result and then, you know, the chemical spills over onto the negative and you realize, oh, this actually fixes the negative image. And it's then the science of photography, you know, or with Alexander Graham Bell and the acid on the phone. And then who was it with Watson? Wasn't it with him?

Dan Sullivan: Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I heard him yell. It wasn't quite as smooth as a Watson. Can you hear me? It was an accident that happened. And so those things, you can be looking for one solution. And that isn't it, but it leads to something else. And the stories of that, especially in medicine, are legion. And then it's putting together those disparate things like we were talking about with GPS. And without smartphones, you could never have Uber or Lyft or any of those kinds of things. So sometimes it was just that technology could not have happened before a lot of other things happened. Satellite technology, you know, radar, microwave, all that sort of thing could not have happened. Which, by the way, quick footnote to the listeners, fascinating movie on the really interesting actress Hedy Lamarr.

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And the invention of things that led to cell phone technology during World War II. You saw that?

Dan Sullivan: Oh, yeah. Well, I've been aware of her for a long time. And, you know, I think, I'm not sure which government that she actually worked with, but she became quite a master of radio waves. Outstanding radio waves. And I think Czech, was she Czech? I think Czechoslovakian or something. She came from Eastern Europe.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. Yeah. But I think that the work she did was in the United States and her father was an inventor.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I mean, it's fascinating. She became famous for one of the first nude movies.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. That's right.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. Ecstasy, it was called. They weren't pulling their punches, you know. But there's this one scene and she's swimming. For a brief second or two or three seconds, you saw, you know, you saw her breasts and it became quite a hit, you know, which you know, leads to all sorts of other industries. Anyway, what I'm playing with is the degree that you think of technology as outside of yourself, as an external force. I think there's a tendency to feel a bit victimized by the technology, because in many cases, it's developing far faster than you can possibly keep up with. We live in sort of a technological universe.

About 40 years ago, I came across a book by a French sociologist by the name of Jacques Ellul, and he wrote a book called The Technological System. And he starts off by saying, you know, up until very recently, every country had its technologies. But now we live in a world where all the countries are inside the technology. If you think about radio, you think about television, if you think about computers, of course, is that we're now inside the technology. And it kind of gives us sort of an alienation feel. And the writer is very alienated by this. He says it's just taking away our humanity. you know, and we've spoken about that on our previous podcast, but I said it's not so much what it is and, you know, how it's happening in our world. It's more of what do you think technology is anyway and do you realize that in being an author of a book, you're using technologies to get your words out to the world. And I was sitting there and I was reading, he was very perceptive, but I could see he was totally alienated by the technological phenomenon. And I said, I think there's another way of looking at this, that maybe we're the technology in the sense of how we think about things.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, maybe it's that we create either the perception of need, or the desire to be able to do something that we couldn't quite fully do before, or we could do it faster, or whatever.

Dan Sullivan: And it's an advantage to know that. It's an advantage to pull that off.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, it is. And I also think that when you are dealing with humans, for the most part, you're dealing with an incredible resistance to change, no matter what that change is. And let's just say that the Hindenburg hadn't blown up, you know, would we be flying around in blimps? You know, because that confirmed the worst fears of everybody right off the bat. And so the use became totally restricted.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, well, Three Mile Island. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah. And it becomes, you know, the it becomes the I told you so, I told you it would never work. But most new ideas are faced with they'll never work.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. That perception.

Jeffrey Madoff: So what is it also about the mindset that keeps somebody or some group pushing in that direction until something can come to fruition?

Dan Sullivan: I find Elon Musk interesting because he's always projecting into the future and says, I think we can do this. I think we can do this. And the truth is that gasoline is just a lot better fuel than electricity is for automobiles. Not so much ultimately in the future. I don't mean ultimately in the future. Electricity may be better, but gasoline or gas, gas and oil, let's say, because gasoline is a by-product of petroleum. It's a further development. But there's just a massive infrastructure for using gasoline that you literally have to create a massive infrastructure for delivering electricity. And there is one. But I've been going back and forth.

People say, well, how do you like the Tesla? We have a Tesla electric car. Babs does. And I said, well, Babs loves her Tesla, and I love Babs. And I'm happy she's happy. I'm happy she's happy. And she does all the driving, so I'm happy with that. But the big thing is that I think that technology starts off as a possibility in a person's mind. Hey, if we arrange things, physically we arrange a number of things together, we can do this. And then in order to continue with your development, you have to sell the idea to other people so that they'll give you money, you know, to develop it. And then you need customers. And then you have to make grand predictions that what I'm doing is creating something new that's going to replace everything that's already there. You know, and there's a whole sales process that's involved in creating new things. He could have never created the Tesla if he didn't get a lot of people investing in it.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, and not to mention that he had a certain jumpstart when he bought the Tesla company. It was already going in that direction. So I think a lot of people don't realize that he didn't start from … no, he was an investor. That's right. Didn't start from ground zero.

Dan Sullivan: Right. Yeah. Yeah. So, but he's obviously, you know, if you take him as a person, I find him very, very interesting in the way that his mind works, you know. And I don't think Tesla is going to be his big thing. I think SpaceX is really going to be his big thing. And I think Starlink, the satellite network, he's got 6,000 satellites up there. You know, and, you know, and again, he's using things that already existed, but he made them better. The fact that his rocket ships can come back, you know, and land after they've gone someplace, they can come back and land. You don't, you know, as NASA did and still does, NASA has part of the rocket come back, but he has the whole rocket come back, you know.

Jeffrey Madoff: What's so interesting to me about that is that Musk and others, although he's out there as the shining example of vision and all these kinds of things, on the other hand, the things that he's done would not have been possible without government-funded research in all kinds of different areas.

Dan Sullivan: So the Cotton Valley wouldn't exist without government research and funding. That's right.

Jeffrey Madoff: And NASA and the work that they've done over the decades, his whole thing about the rocket, and that's an improvement, what you're saying, but it's often given, I think looking at the antecedents that made that possible also increase our understanding of what it is in an interesting way, because it's easier, and I'm just saying this, I haven't thought it through yet, but I think it's true, it's easier to improve on something than it is to originate something. And so to improve on these decades of research that have been done, and then add a new question, which is, how can we bring the whole thing back to cut back on waste, make that usable, reusable, and so on? Again, without all the decades of pre-work and experimentation that were done by NASA, that would have never, ever happened.

So it's kind of interesting, you know, just sort of weighing those things out. You know, you look at Apple computer and you look at, just to set it up as a binary, you look at Jobs and what he did, Steve Jobs, and you look at Bill Gates and what he did. They both created systems that work. On one hand, you can argue that Apple was more innovative in terms of their and made it easier to use the user experience by using the graphical user interface. And none of that was created by Xerox.

Dan Sullivan: That's what I was just going to say. That's right. That they didn't come up with it.

Jeffrey Madoff: That was the famous lawsuit, you know, when Apple sued Microsoft. And it was probably the only funny thing that Bill Gates ever said in court is, well, how could we steal it from you when you stole it from Xerox? You know, the graphical user interface. So it's interesting because think of, and this goes back to our casting not hiring, think about if it was an ensemble of brilliant people. And there were, of course, an ensemble of brilliant people at Microsoft, at Apple. If knowledge was shared, you know, what could that lead to?

Dan Sullivan: I mean, we pick out certain individuals to represent the technology. Let's say there were a thousand that created it. We're picking out one individual to represent the breakthrough. But the nine hundred and ninety-nine were necessary for the breakthrough.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. I think that perspective is missing in a lot of people. They don't really get that, you know, and the tremendous standing on the shoulders of giants that these innovators, they are innovators, but they couldn't have innovated without all the pre-work that had been done.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. I mean, in your case, Jeff, you have a long history of producing things, producing events, showcasing new fashion seasons for Ralph Lauren, Victoria's Secret. And so you have a sense of how the whole thing happens from the initial idea to the actual event when it happens. And then you're doing documentary films and you have a documentary film. And of course, there's a whole technology to creating the documentary film with Lloyd Price. And you're sitting there as more than a documentary filmmaker, you're also thinking, and you're a big fan of the theater. So you go to, you see a lot of theater. You've actually put on events like at Radio City Musical with Liza Minnelli. And my sense is that you were seeing this story that was being videoed, the documentary with Lloyd Price and this story, and you put all that production experience together and say, Lloyd, I think this is a play. Okay? Yes. I would say if you had any of a hundred documentary filmmakers who had done an interview with him, they wanted to put that together, that this should be a play.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, you know, it's interesting because if … So what's the weirdness about you that you did that? Well, one thing about the weirdness about me, the difference is that I am aware, historically, that the initial material for film came from the stage, you know, because there were the scripts, the stories, the characters, all of those kinds of things. I think it's kind of evened out in the sense, you know, a lot of people don't know, for instance, with the Marx Brothers, even The Night at the Opera was a very successful Broadway show before it became a movie. And it led to a movie franchise with the Marx Brothers, a number of films, but I think two or three of them at least started off as Broadway plays. So to me, it goes back to, I haven't thought of this in a long time, but it goes back to the very first, literally the first job I had when I started doing video and film was creating a prototype for video Playboy to present to Christie Hefner, who was going to be taking over the helm of Playboy Enterprises.

And so it was basically a variety show. It didn't have the nudity, it was just for television. And there had been a precursor, which was Playboy After Dark, if you remember that show. And, you know, we had jazz musicians on and comedians, and it was like, you know, the cocktail party you wanted to be at. Rendered much better now by actually Graham Norton, who sort of sets up his own talk show, like it's a cocktail party and you just get to eavesdrop on the scintillating conversation of these celebrities. But what I knew at that point, and Playboy wanted to hire us to do it based on the prototype we created, I saw that every print medium, whether it's Playboy Magazine, The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, whatever, name the magazine, it was I saw back then that ultimately they were going to end up as digital properties online, you know, and using some of the existing technology to do that. And then, of course, developing new technology to move that along faster, better picture quality, faster downloading, all that sort of thing.

So there's a whole cascading of events. So I think that what I recognized with Lloyd, to get back to your question, was that the documentary initiated my desire to do further research, realizing there was a great and this is the overall story that could be told. And how did I want to tell it? Well, I wanted to tell it as a play as opposed to a movie or as opposed to a book. Ultimately, I'd like to cover all three of those. But I thought as a play, they would be the most powerful initially. And musicals in theater have a much higher success rate than musicals in the movies. But I also, I know how I feel when I see a great piece of live theater, and I wanted to create that feeling in the audience of this play.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, what I'm saying is that in this play, you've probably put together dozens and dozens of different capabilities that you've come across since you started your fashion company in 1920, when you were 22. You didn't start it in 1922. You started it when you were 22. And what I'm saying is that what you created was a technology. You were creating the play as it now exists, and going further in the next year, that you're putting together an enormous number of different experiences and experiments that you've done, and successful experiments in other areas, and you're putting all that together, one project into a play. And what I'm saying is that I think you went about this technologically. I think the thinking process that put it together was technological.

Jeffrey Madoff: And so just define for me how you mean that.

Dan Sullivan: In the sense that there's an intention there to do something. And then you start looking, what do I have available for my experience? And then what do I have available in terms of other people's talent? And then there's a certain mode, you know, an accepted mode on how you develop a play. And you know enough about that that you put it together. I go back, you met somebody in London, and they said, you know, for you to get this to the state that it's in now, you know, it's a great play. I've seen it six times. But just the sheer number of details, the sheer number of things that have to be combined here to make this a single production that everybody enjoys, and the performers love being in the play, is thousands and thousands of different things that people have experimented, but it's all coming to a huge impact stage. It's having a huge impact right now.

And what I'm saying in the book that I'm writing is that's how technology gets created. It's this, and it's this, and it's this, and it's this, and it's one person's talent, and it's another person's talent coming together. That's a technological process. And I'm using the word deliberately because I wanted to take the harshness out of technology. You know, I think there's a real harshness to technology now where technological leaders are making huge predictions that require massive amounts of change on the part of everybody else and for their prediction to come true. And I said that we don't like that. We really don't like that. And I don't think we're resisting change. We resist something being forced on us. And I see that a lot. I just see a lot of it because it's so pervasive now with digital. And now that it's in the digital stage. And I said, we all do technology. And truth is, are we resisting change or we don't like their technology interfering with our technology?

Jeffrey Madoff: I think it's a combination really. Because I think that we are resistant to change. Most people are resistant to change. It takes a period of adoption and adjustment in order for that to happen. And, you know, I think back to when I was a kid, I remember all of the resistance to fluoride being in the water, which, you know, demonstrated again and again and again and again, it prevented cavities and prevented cavities to the point that kids who went to the dentist regularly that had fluoride treatments, the new vogue became or the new product to sell was all of a sudden everybody needed braces to straighten their teeth and whitening to whiten their teeth. Because dentists in order to survive had to look at other things aside from just filling cavities, which when we were growing up, that's what dentists did. You know, so the technology can also cause a shift, just like the fear that's happening about AI. There are a lot of people that fear that their professions are at risk because AI can do it so much cheaper.

Dan Sullivan: Can do something much more cheaply. Yes. Yeah. I think the verdict is still out whether it can do what they're doing. I mean, I think this has always been the case from the first rock thrower, you know, that I'm not going to learn throwing rocks, you know. In other words, I go back to the advantage stage. When one person creates something new, that's an advantage. It creates a sudden inequality in social affairs, you know, and people respond differently to someone else's advantage. Some people say, oh, I want to learn that advantage too. And some people say, I want to prevent that advantage from existing.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, so here's an example of that. When I was in high school, I took typing. I was the only male in the class that took typing. And the teacher said, what are you doing in here? Because this was for, you know, women who were destined to become secretaries or office workers of some sort. Why are you taking typing? Well, I have a sister who's four years older than I am. She learned how to type and she made her spending money in college typing people's papers because she could type really fast. And, you know, at that time you made had an extra 10, 20 bucks, that could buy you a good weekend of fun. So I decided this is a skill worth learning.

Little did I know that it would eventually lead to me being an early adopter in computers because the keyboard, the input device, was something I was already really comfortable with. So I was able to do word processing right away, where it wasn't a steep learning curve for certain things. And it's because I had learned that precursor to the how to input on that new device, the personal computer, because I had learned typing and the typewriter was not intimidating to me. The keyboard wasn't intimidating to me. And the reason that IBM missed out so hugely on the personal computer is they thought that no male executive would want to have a keyboard on their desk because it made them look like a secretary. Now, who doesn't have a keyboard on their desk? You know, it's essential. But again, it's that resistance to change.

Dan Sullivan: Well, it's the resistance to change on the part of some people, but it's also some people immediately seeing the advantage, to use your case. You immediately saw the change. So what I'm saying is there's a real inequality here of aspiration, if you will. But there are some people who just like learning new things because they don't know how it's going to be useful, but it's probably going to be useful. So I'm looking at the mind here that sees opportunity, it sees advantage when other people don't see opportunity advantage. And I think this has always been true. I agree with you.

Jeffrey Madoff: I agree. I mean, a big shift that happened in production, I mean, I knew film and video. I was self-taught in those areas. I didn't go to school for it, but I learned those areas. Yeah. When it was clear that digital was going to end up being the image capture and, you know, film because of expense and there was a lot more craft in film. Initially video was an engineer's medium. And you had to have tremendous amount of light and you couldn't make it pretty at all. It didn't have the nuances at all in film and it's grayscale and black and white or the spectrum of colors. And so I knew a lot of cinematographers. So I'm not gonna learn video. I think it's shit. I said, well, it is now. But in a very few years, it's not gonna be, and the gap is gonna narrow and narrow and narrow and narrow until most of the public, 99%, can't tell the difference between the two.

And it's a technology that is, there's certain technologies that become inevitable. It's gonna happen whether you like it or not. So you can either adopt the technology and learn how to use it and benefit from it, or you can be arrogant and resistant to that change at your own peril. So seeing that entire shift from film to video in a lot of cases, you know, Steven Spielberg can still afford to shoot everything he wants and do whatever he wants on film. Most movies are shot digitally now. It comes down to then something else, your book that you wrote with Ben Hardy, Who Not How, which is finding the people who know how to do that so you can learn and inform yourself so you aren't left behind. And I think that's really interesting, because there also are always those early adopters who see the opportunity. And I think that's in everything where technology comes in.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, it's a really interesting thing, but what I'm trying to get away is not thinking of your computer as technology, but it's the present result of millions of things being put together for different reasons that at some point it became this computer.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, I guess we don't think of, you know, go back to our earlier input devices, so to speak, and you've got, you know, the quill and ink, which over the centuries became a keyboard.

Dan Sullivan: Or it became a better quill that has an ink reserve and then it became a ballpoint. The basic thing was that it's kind of messy, the quill and the inkwell. You have to do it and you have to be really, really good at it. But for a lot of people to be able to do it, you can't depend upon quills and inkwells. It's actually, how can a lot of people do this without almost knowing how to do it? I mean, some of the ballpoints now are really fantastic. I'm really amazed at some of the pens that you have that just they just do what they're supposed to do. So a certain sense there's making things automatic. If you want a large number of people to do this, you got to make it really easy.

Jeffrey Madoff: That's right. Yeah, absolutely.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And they don't have to understand how the thing works. They just have to, you know, learn the skill of using it.

Jeffrey Madoff: I built my first computer from a kit. It was an Eagle computer. And because I wanted to understand how it worked … like prior to that, when I worked at a motorcycle shop, I took apart and put together my motorcycle. Only wanted to do that once. But I did it and it gave me an understanding of it. Back to your earlier question today about when I started at a fashion company, it was also cutting apart a shirt and a jacket and pants at their seams so I could see what the parts were. And then I learned, of course, how you lay out those parts on the fabric to maximize the usage of the fabric and minimize the amount of waste, because it's expensive, you know. I think that one of the things that triggers people about technology is the fear that it's going to eliminate a large swath of jobs. And I think that's one of the things that is going on in spades with AI right now, from the actor strike, the writer's strike. Programmers. And even, you know, catalog writers and even, you know, contract review, all kinds of things that are really boilerplate kinds of jobs. So I think, you know, with the hype phase of AI makes it seem like it can do everything faster and better. But as you actually use it, you realize there's a lot of limitations that aren't going to go away quickly, even though it keeps getting better and better in certain realms.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. From your knowledge, would you say that the really smart writers are using AI?

Jeffrey Madoff: No.

Dan Sullivan: I don't mean as a final product, but to gather the information and to organize the project.

Jeffrey Madoff: I think there is a tradition in writing. I will write certain, I'll write notes in longhand, but I will put stuff together using a computer, not AI. I'm just talking about the storage of the information so I don't lose the piece of paper. But I like writing something down because there's also, I remember it better if I actually write it. And there's, you know, science behind that. I don't know if younger writers, because they grew up using computers, that they don't bother. But I think there are a number of younger writers and I'm calling younger writers, even writers, let's say, from 50 and under, that I think a lot of them still like the tradition of writing on legal pads, you know, with a fountain pen or a ballpoint. And they like that. And then when they get closer, maybe they, you know, maybe they do it with a program, you know, or something.

Dan Sullivan: Well, one thing, I think it's inevitable that we're going to be using AI. But what I think is that all the technologies we're presently using will have AI in the computer. I mean, for all I know, there's a lot of AI in the computer that we're using today for our podcast.

Jeffrey Madoff: So, a good example of that, by the way, is that most of us use Microsoft Word for the word processing, but whatever word processing program you use, spellchecker is AI. The problem is, if I say, no Dan, that isn't right, and I spell the K-N-O-W, wouldn't be picked up as a mistake because of the context, wouldn't be picked up as a mistake. And so it's interesting because that's, you know, of course, some of the problems is that the context has not been adequately taken into consideration. So, you know, I think it's, we've been using AI for a long time. You know, every time you get customer service and it's all these prompts and then recorded responses to text customer service, that's all, essentially that's AI. Search their database, find the word, even if you get sometimes an answer that makes no sense, but you know, that's all AI. So you're right, there's a lot of things. They're already AI.

Dan Sullivan: I keep talking to the tech people and I say, you know, if you do the history of electrification, you know, bringing electricity in, I said, nobody remarks that they have electricity today, okay? But even 100 years ago, people were still in the learning stages of electricity. You know, the farm that I grew up on, I was born in ‘44, that farm had only been electrified for 16 years when I was born. And you could see that you didn't have much electricity available in the house because you'd have to do a real do-over, you know, and you're putting in circuits and the circuitry behind the walls and everything else. So we didn't have many outlets. Okay, and so the whole thing, there are certain technologies which are enormously adaptable. If you can, you know, the microchip, for example, is enormously adaptable. You can pretty well put microchips in everything and it speeds things up, makes them easier to use. But you can also use microchips to make more powerful microchips, you know, and everything else.

So there are certain technologies, I think language is a technology, and English has more or less taken over the world. And I think part of the reason is that English is the easiest language on the planet to speak badly and be understood. So there are certain technologies which have sort of a very adaptable future. You can use it for this, you can use it for this, and you can use it for that. So I'd like to sort of sum up here what we're talking about. I think you're involving yourself in the most powerful technology that's ever been created.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which is?

Dan Sullivan: The story.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, because I was going to ask you about the description you were giving, and the fundamental story is language. And I think from your definition, and I don't disagree with this, language could be looked at as a technology. I think it is.

Dan Sullivan: I think it is. And one of the things I'm interested in is The Oxford English Dictionary because I have the complete set. My staff, they said, what do you get Dan for Christmas? They bought me the, you know, it's 20 volumes and some letters like S, it's one and a half volumes just with words starting with S. But It's not all that useful as a dictionary, you know, but what it is, is a terrific history book of how words form, you know. I mean, you can have a word and you get two and a half pages. In 1352, it was used this way, and then it changed to this and this, and just shows you how this word changed over time. So, you know, I'm trying to establish that almost everything humans do that improves over time is done technologically. Testing and checking it out. Does it work here? Does it work there? And the ones that work really in many, many situations for different reasons really become powerful technologies. And the story, I think, is perhaps the most powerful technology that humans have ever put together.

Jeffrey Madoff: I wonder if it's the most personal technology, or is it a way to both educate and bond? Because I think also people tend to think of technology as some sort of appliance, or some component of an appliance, or something.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah, and I think it's a way of putting things together, you know. I'll give you a story. Shannon Waller has a daughter who's 24, I think, 24 years old. But when she was born, they went to a school that showed how you can teach children sign language before you teach them how to, before they'll learn how to talk. And so when Madison was probably I would say maybe a year and a half, she knew 75 words that she could do with her hands. And then there was one day where for the first time she told a story. And she had for a nap was a, a nap was a light sleep and an overnight was a dark sleep. And she had dark and she had sleep. She had those words. And she said, basically the gist of what she said to Shannon was, yesterday we were in the park and I saw a bird and then I had a dark sleep, and today I saw the same bird. And it was like a story. She told a little story. And one week later, she started to talk. She had gotten so used to the hands and developed, she was starting to develop stories. And when she talked, she learned how to talk really, really quickly. And I'm saying that her sign language was a technology that took her to the threshold of speaking. I mean, there's a certain point just how the mouth develops and the tongue develops and everything. They can't really pull it off, you know, until they get to a certain age. But the moment she did, she already had the structure of story in her brain.

Jeffrey Madoff: It's interesting. Margaret recorded, and I have twins, as you know, and Margaret recorded others particularly verbal. And before she was able to make sounds that you could make things out of, there is a kind of, what we saw when Margaret was recording him, she'd leave her recorder on all night, and you would start hearing in the gibberish that she would say, you could start to discern words being formed. It's really interesting, you know, what she did. I'm sure there's been studies actually done like that, but this is something Margaret came up with. And it was really quite fascinating because you, it's, I called it verbal hieroglyphics, if you will. You know, these sounds that eventually led to the words because she couldn't actually say those words yet. But there was a noticeable and fairly obvious evolution of the ability to speak.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And would you say it's a constant experimentation with things?

Jeffrey Madoff: Oh, yeah. Yeah. Yeah, absolutely. And also, you know, getting the result you want. Yeah. You know, how do you communicate to get the result you want? You know, and that kind of communication is interesting. It's kind of, you know, maybe a baby cries and maybe a business person, you know, tries to butter you up to get what they want and then take advantage. But we learn different modes. And again, I think it first starts off with survival modes. I need food. I need liquid, you know, and it's, seeing a child development like that is quite fascinating.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. Yeah. And of course, our brain has developed. I mean, we have our individual brain, but the structure of the brain has developed over, you know, there's Professor Henrik, Joe Henrik, and he said that humans created this other intelligence, and it was that we created social intelligence, that we found out that we had our own intelligence, but that we could benefit from other people's intelligence. And the groups that were best at this shot ahead politically, militarily, and everything because they could operate as a group. But he said the interesting thing is that the structure of the brain was actually changing as people were doing this. And so we're probably, his estimate is a million years that humans have been distinct for a million years from whatever we came from. But I think that we're at a point now where technology is so pervasive that we've got to rethink this from a standpoint that maybe we're all technological and we would be better served rather than trying to learn technologies to understand that we go about things technologically. And anytime you put one thing together with another, you've created the beginning of a technology. And then if you add a third thing, it gets more interesting. You add a fourth thing, it gets more interesting. And that there's real power in that, and there's real progress in that. And that would be a better way to approach your life than worrying about all the technology that's intruding on you.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, I agree with you, and it's fascinating, because as you were talking about this stuff, I was thinking about childhood. And I was thinking about, there were two things that most of us had in terms of popular toys. Tinker toys, which one could argue is the precursor of Legos.

Dan Sullivan: It totally is.

Jeffrey Madoff: And erector sets.

Dan Sullivan: Erector sets, yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: You know, where you could build things. And in a sense, and I don't think this is a stretch, is you could build things and the component parts were the words of the story of the finished thing. So if you built that, you had the Rector set with the motor, and you built that Ferris wheel, it was, you know, you were trying to create the end result story, if you will, using those component parts, you know, to make it. And I think that there's something incredibly valuable about holding something in the tactile aspect that learning also is, that's really quite fascinating. And Legos, I guess, just got it more right than any other company in terms of creating that. And the ability of taking those component parts and building it into something, in some cases, extraordinary.

Dan Sullivan: 75 years now since the first Lego set.

Jeffrey Madoff: I didn't have Legos when I was a kid. I did have these little plastic blocks, but not Legos.

Dan Sullivan: No, we had the balls and the sticks and you could create all that was the Tinker Toy, I think. Yeah. Yeah.

Jeffrey Madoff: And think of the name of that. Dear Tinkering.

Dan Sullivan: That's right. Yeah. Yeah, yeah. Anyway, I wanted to try this out on you because I'm thinking it through as I'm writing the book. But I get a sense that learning is, all learning comes from putting things together. And the best learning is where you put things together in a new way.

Jeffrey Madoff: And I would posit that it's that new way presupposes antecedents, things that came before it. And so I think that one would do well to understand the history, if you will, and the context of whatever that is. Because I think it can be more effective at creating new things.

Dan Sullivan: Learn anything? Nah.

Jeffrey Madoff: Yeah, I mean, it's, you know, it's when something becomes familiar. I think this is my main takeaway. When something becomes familiar, we no longer look at it as technology. It's just something you use. It's a tool, which is what I think technology is anyhow, you know, so back when it was in the days of the manual typewriter, and then the big, big thing that happened was electric typewriters.

Dan Sullivan: Especially the Selectric typewriter.

Jeffrey Madoff: The Selectric, yeah, the IBM with the ball. And so the keys couldn't get all jammed up together. But I think that we stopped looking at it as technology once it's in common usage. And technology is, in most cases, I think, applied to something that is new. And then there's always the one camp that thinks it's a threat and going to destroy things, and the other that thinks it's going to be a utopian aid to a better world. And it always ends up somewhere in between.

Dan Sullivan: But there's new things coming along at the same time.

Jeffrey Madoff: Which I think is also interesting, because you can learn a lot from things that don't work. You know, why didn't that work? You know, what about the people that actually, although they enjoyed Avatar, they didn't want 3D as a part of their day-to-day life, you know? So I think it's really fascinating what we classify as technology, why we classify it as it, and during the early hype phases of new technologies. And I think one of the other things is, that's dangerous about it is that because, like you were saying, you can type a question into Perplexity and get an answer in a few seconds. I think that there's a lot of answers that don't come in a few seconds, that they take time to percolate, to process, to test, to know whether or not that, in fact, is an answer or going in the right direction. But I think we've grown so impatient with process that we want everything, including correct knowledge, right away. And that doesn't happen.

Dan Sullivan: Well, it's not wisdom. And there's a big difference between knowledge and wisdom.

Jeffrey Madoff: Right. Yeah. Yeah. All right. Well, I'm very pleased with the exploration.

Dan Sullivan: Yeah. And I'm very … yep. That'll be it for today.

Jeffrey Madoff: Well, then I guess that's goodbye for today to anything and everything. Thank you, Dan Sullivan. I'm Jeff Madoff. Hope you got some of this. Thanks for joining us today on our show, Anything and Everything. If you enjoyed it, please share it with a friend. For more about me and my work, visit acreativecareer.com and madoffproductions.com. To learn more about Dan and Strategic Coach, visit strategiccoach.com.

Related Content

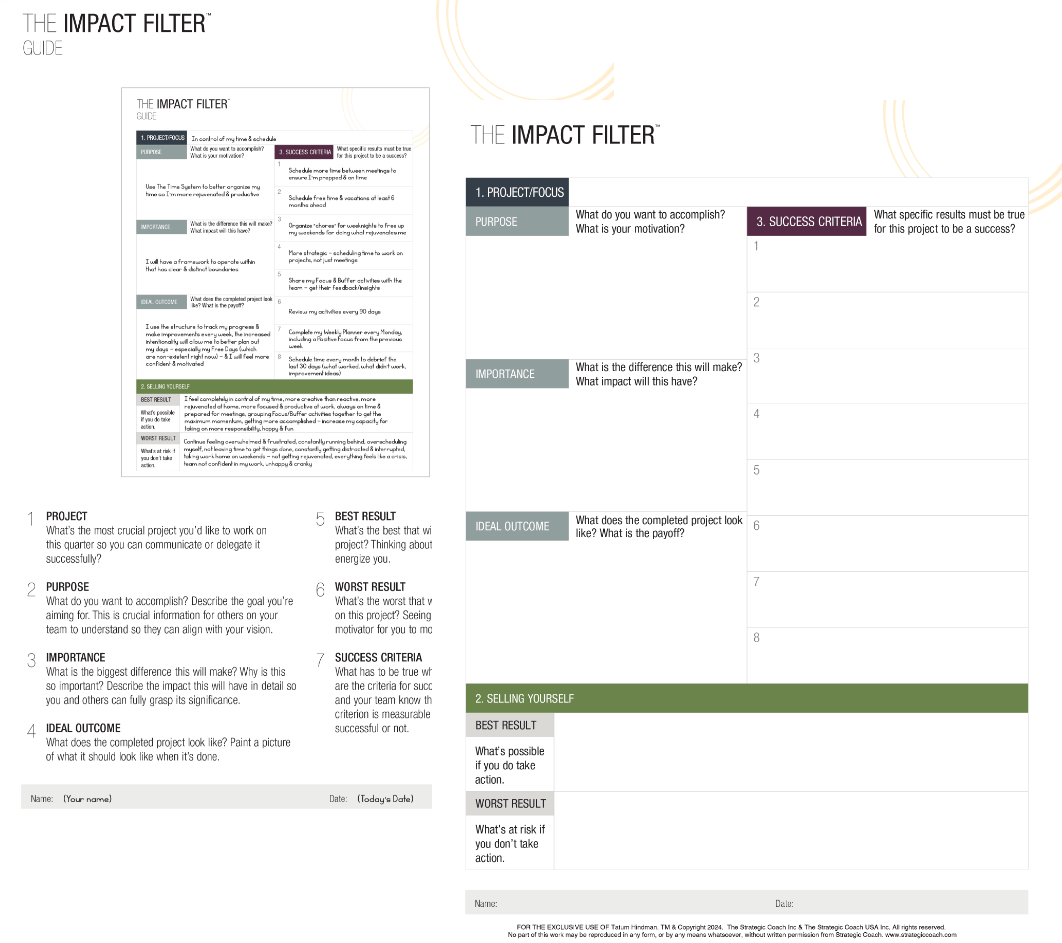

The Impact Filter

Dan Sullivan’s #1 Thinking Tool

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed by your goals? The Impact Filter™ is a powerful planning tool that can help you find clarity and focus. It’s a thinking process that filters out everything except the impact you want to have, and it’s the same tool that Dan Sullivan uses in every meeting.